by Lee Gesmer | Nov 27, 2023 | Copyright, General

If you follow developments in artificial intelligence, two recent items may have caught your attention. The first is a Copyright Office submission by the VC firm Andreessen Horowitz warning that billions of dollars in AI investments could be worth less if companies developing this technology are forced to pay for their use of copyrighted data. “The bottom line is this . . . imposing the cost of actual or potential copyright liability on the creators of AI models will either kill or significantly hamper their development.”

The second item is OpenAI’s announcement that it would roll out a “Copyright Shield,” a program that will provide legal defense and cost-reimbursement for its business customers who face copyright infringement claims. OpenAI is following the trend set by other AI providers, like Microsoft and Adobe, who are promising to indemnify their customers who may fear copyright lawsuits from their use of generative AI.

Underlying these two news stories is the fact that the explosion of generative AI has the copyright community transfixed and the AI industry apprehensive. The issue is this: Does copyright fair use allow AI providers to ingest copyright-protected works, without authorization or compensation, to develop large language models, the data sets that are at the heart of generative artificial intelligence? Multiple lawsuits have been filed by content owners raising exactly this issue.

The Technology

The current breed of generative AIs is powered by large language models (LLMs), also known as Foundation Models. Examples of these systems are ChatGPT, DALL·E-3, MidJourney and Stable Diffusion.

This technology requires that developers collect enormous databases known as “training sets.” This almost always requires copying millions of images, videos, audio and text-based works, many of which are protected by copyright law. When the data is scraped from the web this is potentially a massive infringement of copyright. The risk for AI companies is that, depending on the content (text, images, music, movies), this could violate the exclusive rights of reproduction, distribution, public performance, and the right to create derivative works.

of images, videos, audio and text-based works, many of which are protected by copyright law. When the data is scraped from the web this is potentially a massive infringement of copyright. The risk for AI companies is that, depending on the content (text, images, music, movies), this could violate the exclusive rights of reproduction, distribution, public performance, and the right to create derivative works.

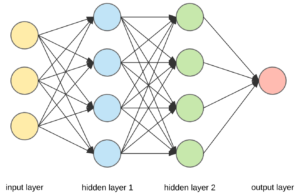

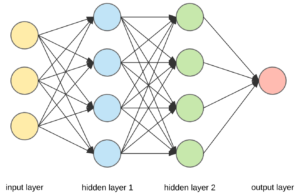

However, for purposes of copyright fair use analysis it’s important to recognize that the downloads are only an intermediate step in creating an LLM. Greatly simplified, here’s how it works:

In the process of creating an LLM model words are broken down into tokens, numerical representations of the word. Each token is a unique numerical ID. The numerical IDs are then transformed into high-dimensional vectors. These vectors are learned during the model’s training and capture semantic meanings and relationships.

Through multiple layers of transformation and abstraction the LLM identifies patterns and correlations within the data. Cutting edge systems like GPT-4 have trillions of parameters. Importantly, these are not copies or replications of the copyright-protected input data. This process of transformation minimizes the risk that any output will be infringing. A judge or jury viewing the data in an LLM would see no similarity between the original copyrighted text and the LLM.

Is Generative AI “Transformative“?

Because the initial downloads in this process are copies, they are technically a copyright infringement – a “reproduction.” Therefore, it’s up to the AI companies to present a legal defense that justifies the copying, and the AI development community has made it clear that this defense is based on copyright fair use. At the heart of the AI industry’s fair use argument is the assertion that AI training models are “non-expressive uses.” Copyright protects expression. Non-expressive use is the use of copyrighted material in a way that does not involve the expression of the original material.

Because the initial downloads in this process are copies, they are technically a copyright infringement – a “reproduction.” Therefore, it’s up to the AI companies to present a legal defense that justifies the copying, and the AI development community has made it clear that this defense is based on copyright fair use. At the heart of the AI industry’s fair use argument is the assertion that AI training models are “non-expressive uses.” Copyright protects expression. Non-expressive use is the use of copyrighted material in a way that does not involve the expression of the original material.

For the reasons discussed above, the AI industry has a strong argument that a properly constructed LLM is a non-expressive use of the copied data.

However, depending on the specific technology this may be an oversimplification. Not all AI systems are the same. They may use different data sets. Some, but not all, are designed to minimize “memorization” which makes it easier for end users to retrieve blocks of text or infringing images. Some systems use output filters to prevent end users from utilizing the LLM to create infringing content.

For any given AI system the fair use defense turns on whether the LLM is trained and filtered in such a way that its outputs do not resemble protected inputs. If users can obtain the original content, the fair use defense is more difficult to sustain.

There is a widespread assumption in the AI industry that, assuming an AI is designed with adequate safety measures, using copyright-protected content to train LLMs is shielded by the fair use doctrine. After all, the reasoning goes, the Second Circuit allowed Google to create a searchable index of copyrighted books under fair use. (Google Books, Hathitrust). And the Supreme Court permitted Google to copy Oracle’s Java API computer code for a different use. (Oracle v. Google). AI companies also point to cases holding that search engines, intermediate copying for the purpose of reverse engineering and plagiarism-detection software are transformative and therefore allowed under fair use. (Perfect 10 v. Google; Sega Enterprises v. Accolade; A.V. et al. v. iParadigms)

In each of these cases the use was found to be “transformative.” So long as the act of copying did not communicate the original protected expression to end users it did not interfere with the original expression that copyright is designed to protect. The AI industry contends that LLM-based systems that are properly designed fall squarely under this line of cases.

How Does Generative AI Impact Content Owners?

In evaluating AI’s fair use defense the commercial impact on content owners is also important. This is particularly true under the Supreme Court’s decision earlier this year in Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith. In Warhol the Court taught that, in a case that involved commercial copying of photographs, the fact that the copies were used in competition with the originals weighed against fair use.

AI developers will argue that, so long as users can’t use their generative AI systems to access protected works, there is no commercial impact on content owners. In other words, like in Google Books, the AI does not substitute for or compete with content owners’ original protected expression. No one can use a properly constructed AI to read a James Patterson novel or listen to a Joni Mitchell song.

The AIs should be able to distinguish Warhol by pointing out that they are not selling the actual copyrighted books or images in their data sets, and therefore – like in Google Books – they are causing the content owners no commercial harm. In other words, the AI developers will argue that the “intermediate copying” involved in creating and training an LLM is transformative where the resulting model does not substitute for any author’s original expression and the model targets a different economic market.

Does the authority of Google Books and the other intermediate copying cases extend to the type of machine learning that underpins generative AI? While the law regulating AI is in its infancy, several recent district court cases have given plaintiffs an unfriendly reception. In Thomson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence the defendant used West’s head notes and key number system to train a specialized natural language AI for lawyers. West claimed infringement. A Delaware federal district court judge denied Ross’s motion for summary judgment based on fair use, and held that the case must be decided by a jury. However, relying on the intermediate copying cases, the judge noted that Ross would have engaged in transformative fair use if its AI merely studied language patterns in the Westlaw headnotes and did not replicate the headnotes themselves. Since this is in fact how LLMs are trained on data, Ross’s fair use defense likely will succeed.

generative AI? While the law regulating AI is in its infancy, several recent district court cases have given plaintiffs an unfriendly reception. In Thomson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence the defendant used West’s head notes and key number system to train a specialized natural language AI for lawyers. West claimed infringement. A Delaware federal district court judge denied Ross’s motion for summary judgment based on fair use, and held that the case must be decided by a jury. However, relying on the intermediate copying cases, the judge noted that Ross would have engaged in transformative fair use if its AI merely studied language patterns in the Westlaw headnotes and did not replicate the headnotes themselves. Since this is in fact how LLMs are trained on data, Ross’s fair use defense likely will succeed.

In a second case, Kadrey v. Meta, the plaintiffs, book authors, claimed that Meta’s inclusion of their books in its AI training data violated their exclusive ownership rights in derivative works. The Northern District of California federal judge dismissed this claim. The judge noted that the LLM models could not be viewed as recasting or adapting the plaintiff’s books. And, the plaintiffs had failed to allege that the content of any output was infringing. “The plaintiffs need to allege and ultimately to prove that the AI’s outputs incorporate in some form a portion of the plaintiffs’ books.” Another N.D. Cal. case, Andersen v. Stability AI is consistent with these rulings.

While these cases are early in the evolution of the law of artificial intelligence they suggest how AI developers can take precautions to insulate themselves from copyright liability. And, as discussed below, the industry is already taking steps in this direction.

The Industry Is Adapting To The Copyright Threat

In the face of legal uncertainty, the AI industry is adapting to legal risks. The potential damages for copyright infringement are massive, and the unofficial Silicon Valley motto – “move fast and break things” – doesn’t apply with the stakes this high.

ChatGPT4: Create an image showing Jack Nicholson in The Shining

Early in the current generative AI boom (only a year ago) it was possible to use some of these systems to generate copyright- protected content. However, the dominant AI companies seem to have plugged this hole. Today, if I ask OpenAI’s ChatGPT to provide the lyrics to “All Too Well” by Taylor Swift it declines to do so. When I ask for the text of the opening paragraph of Stephen King’s “The Shining,” again it refuses and tells me that it’s protected by copyright. When I ask OpenAI’s text-to-image creator Dall·E for an image of Batman, Dall·E refuses, and warns me that what it will create will be sufficiently different from the comic book character to avoid copyright infringement.

These technical filters are illustrative of the ways that the industry can address the copyright challenge, short of years of litigation in the federal courts.

The first, and most obvious, is to train the systems not to provide infringing output. As noted, Open AI is doing exactly this. The Shining may have been downloaded and used to create and train Chat GPT, but it won’t let me retrieve the text of even a small part of that novel.

ChatGPT4: Create an image of Taylor Swift performing her song “All Too Well”

Another technical measure is minimization of duplicates of the same work. Studies have found that the more duplicates that are downloaded and processed in an LLM the easier it is for end-users to retrieve verbatim protected content. “Deduplication” is a solution to this problem.

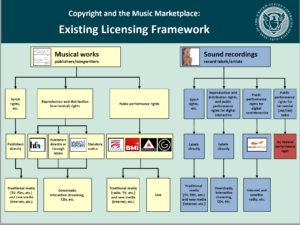

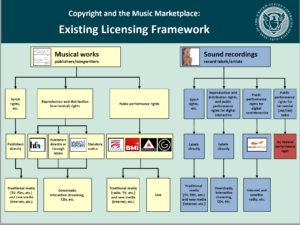

Another option is to license copyrighted content and pay its creators. While this would be logistically challenging, a challenge of similar complexity has been met in the music industry, which has complex licensing rules that address different types of music licensing and a centralized database system to make that process accessible. If the courts prove to be hostile to AI’s fair use defense the generative AI field could evolve into a licensing regime similar to that of music.

Another solution is for the industry to create “clean” databases, where there is no risk of copyright infringement. The material in the database will have been properly licensed or will be comprised of public domain materials. An example would be an LLM trained on Project Gutenberg, Wikipedia and government websites and documents.

Given the speed at which AI is advancing I expect a variety of yet-to-be conceived or discovered infringement mitigation strategies to evolve, perhaps even invented by artificial intelligence.

International Issues

Copyright laws vary significantly across countries. It’s worth noting that there has been more legislative activity on the topics discussed in this post in the EU than the US. That said, as of the date of this post near the close of 2023 there is no consensus on how LLMs should be treated under EU copyright law.

post in the EU than the US. That said, as of the date of this post near the close of 2023 there is no consensus on how LLMs should be treated under EU copyright law.

Under a recent proposal made in connection with the proposed EU “AI Act,” providers of LLMs would need to “prepare and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary of the content used to train the model or system and information on the provider’s internal policy for managing copyright-related aspects.”

Additionally, they would need to demonstrate “that adequate measures have been taken to ensure the training of the model or system is carried out in compliance with Union law on copyright and related rights . . .”

The second of these two provisions would allow rights holders to opt out of allowing their works to be used for LLM training.

In contrast, the recent US AI Executive Order orders the Copyright Office to conduct a study that would include “the treatment of copyrighted works in AI training,” but does not propose any changes to US copyright law or regulations. However, US AI companies will have to pay close attention to laws enacted in the EU (or elsewhere), since – as has been the case with the EU’s privacy laws (GDPR) – they have the potential to become a de facto minimal standard for legal compliance worldwide.

Andreessen Horowitz and the Copyright Shield

What about the two news items that I mentioned at the beginning of this post? With respect to the Andreessen Horowitz warning of the cost of copyright risk on AI developers, in my view the risk is overstated. If AI developers design their systems with the proper precautions, it seems likely that the courts will find them to qualify for fair use.

As to OpenAI’s promise to indemnify end users, the risk to OpenAI is slim, since its output is rarely similar to inputs in its training data and its filters are designed to frustrate users who try to output copyrighted content. In any event end users are rarely the targets of infringement suits, as seen in the many copyright suits that have been filed to date, which all target only AI companies as defendants.

The Future

The application of US copyright law to LLM-based AI systems is a complex topic. I expect more lawsuits to be filed as what appears to be a massive revolution in artificial intelligence continues at breakneck speed. While traditional copyright law seems to favor a fair use defense, the devil is in the details of these complex systems, and the legal outcome is by no means certain.

***

Selected pending cases:

Andersen v. Stability AI, N.D. Cal.

J.L. v. Alphabet Inc., N.D. Cal.

P.M. v. OpenAI, N. Dist. Cal.

Doe v. GitHub, N.D. Cal

Thomson Reuters Enter. Ctr. GmbH v. Ross Intel. Inc., D. Del.

Kadrey v. Meta, N.D. Cal.

Sancton v. OpenAI, S.D. N.Y.

Doe v. GitHub, N.D. Cal.

by Lee Gesmer | Oct 26, 2023 | Copyright, General

By Lee Gesmer and Andrew Updegrove

Every citizen is presumed to know the law … and it needs no argument to show… that all should have free access to its contents.

U.S. Supreme Court in Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org (2020)

Many private organizations promulgate best-practice standards. Two examples you might be familiar with are the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM).

In the U.S., unlike most foreign countries, standards are developed “from the bottom up” by the private sector, rather than “from the top down” by government agencies or quasi-public bodies. In keeping with this division of labor, government agencies have come to rely extensively on private sector standards developers to provide standards suitable for adoption as regulations.

Federal law permits federal agencies to incorporate privately developed standards into law by referencing them in the Federal Register without reproducing them there. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) has more than 27,000 incorporated standards. States and municipalities do this as well, adding to that number. Once adopted the standards carry the force of law.

These private-government relationships are crucially important – they leverage specialized knowledge and industry expertise to formulate robust and reliable standards that the government could not create by itself, and save untold millions of tax dollars in avoided costs for government agencies that would otherwise have to generate them. The standards organizations that provide standards referenced into law, in turn, gain legal legitimacy and wider application for their standards.

There is also a commercial side to these relationships – many standards organizations support themselves in part by the sale of their standards.

Public.Resource.Org (Public Resource) is a nonprofit group that disseminates legal materials. Its website has posted thousands of standards, including those produced and copyrighted by ASTM. ASTM (along with two other standards organizations) sued Public Resource for copyright infringement. The case has been working its way through the courts for a decade. Absent a successful appeal to the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia finally decided the issue on September 12, 2023. It held that the non-commercial dissemination of these standards as incorporated by reference into law constitutes copyright fair use, and therefore cannot support liability for copyright infringement.

As we have observed on many occasions, copyright fair use is an unpredictable legal doctrine. Often, the outcome seems to be in the eye of the beholder – the judge or judicial panel – rather than the result of any predictive legal test. A recent example of this is Goldsmith v. Warhol: a federal district court held that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo of Prince was fair use. The Second Circuit reversed, holding that it wasn’t. The Supreme Court upheld that ruling, but under a different rationale from the Second Circuit. Three courts, three different approaches to fair use. For another example see Final Thoughts On Google v. Oracle. The result is a confusing body of law that lacks predictability for the copyright community, both authors and the lawyers that are asked to advise them.

D.C. Circuit’s Holding in ASTM

While Warhol involved art and Oracle software, ASTM involved privately developed technical standards that had been incorporated into law “by reference.”

There is no question that in most cases technical standards are copyrightable – that is, they reflect sufficient originality to be protected by U.S. copyright law. Hence, without an affirmative defense Public Resource’s reproduction and distribution of ASTM’s standards infringed its copyrights. Public Resource’s defense was copyright fair use.

The D.C. Circuit applied – as it must – the four-factor fair use test:

Purpose and Character of the Use. Under the first factor it found that the “purpose and character“ of Public Resource’s nonprofit status favored fair use. Further Public Resource’s use of the standards – to provide a free repository of the law – is “transformative,” a key issue in any fair use case. While in most cases the term “transformative” involves changes to the work, here the court construed it to mean a transformative “use” of the work.

Nature of the Copyrighted Work. Factor two also favored fair use. Because the court viewed the standards as “factual” in nature – a conclusion we find questionable – it conclude that they “fall at best, at the outer edge of copyright’s protective purposes.” Factual works are often given “weak” or “thin” copyright protection, and because protection is weaker for such works, it’s easier to establish fair use.

Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used. Under factor three, although Public Resource copied the standards in their entirety, the court found that this was necessary in light of the purpose. “If an agency has given legal effect to an entire standard, then its entire reproduction is reasonable in relation to the purpose of the copying . . ..” This is not unusual in the context of copyright fair use – many fair use cases involve comprehensive copying. Oracle is a good example of this.

Effect of the Use Upon the Potential Market for or Value of the Copyrighted Work. Lastly, the fourth fair use factor required the court to consider the “market harm“ caused by Public Resource’s copying, including any substantially adverse impact on the “potential market“ for the original standards. While the court observed that it “seems reasonable” to suppose that economic harm might result, it found that the plaintiffs could not quantify past or future financial harms, relying instead on “conclusion, assertions and speculation.“ In any event, even if Public Resource’s free postings lowered the demand for the plaintiffs’ standards, this was outweighed by “the substantial public benefits of free and easy access to the law.“ The court concluded that the fourth fair use factor did not tip the balance one way or the other. But because the first three factors “strongly“ favored fair use, it found that Public Resource’s non-commercial posting of standards incorporated into law by reference is fair use.

Legal Precedents Favored Public Resource

The extent to which the law should be in the public domain is not a new issue for copyright law. In 2020 the Supreme Court held that annotations to Georgia’s official statutory code, as government edicts, were free from copyright. In that case the Court didn’t even reach fair use – it held that officials who “speak with the force of law” cannot claim copyright in the works they create in the course of their official duties.” Georgia v. Public Resource.

The lower courts have also weighed in on this issue. In Veeck v. Southern Building Code the Fifth Circuit relied on fair use to hold that model building codes adopted by reference could be copied. In Building Officials & Code Administration. v. Code Technologies, Inc. the First Circuit suggested that once a model building code has been adopted into law it is in the public domain, and remanded for further consideration.

Public Resource relied heavily on these cases on appeal, and indeed, these precedents put ASTM and its co-plaintiffs in an uphill battle heading into the appeal to the D.C. Circuit.

Copyright Fair Use Based On “Public Benefits”

While not explicitly identified in the Copyright Act, the “public benefit” theory of fair use prioritizes societal and cultural benefits in the application of copyright law. A recent example of this is the Supreme Court’s holding in Oracle v. Google. In this 2021 case the issue was whether Google’s use of Oracle’s Java API (Application Programming Interface) in its Android operating system constituted fair use. While Google copied all of Oracle API and used it commercially, the Court found fair use, based in part on the benefit to the software development industry and technical innovation. As the Court said, “we must take into account the public benefits the copying will likely produce.”

Similarly, in the 2015 Google Book Search decision, Author’s Guild v. Google, the Second Circuit recognized the substantial public benefits of Google’s project in concluding that Google’s verbatim copy of books was protected by fair use.

The D.C. Circuit’s ruling in the ASTM case follows this line of reasoning. Just as there is a public benefit in allowing software developers to use the Java API, and a public benefit in allowing the public to search copyright-protected books for relevant “snippets,” so does the publication of laws incorporated by reference benefit the public by making the law more accessible. However, as we discuss below, it did this at the risk of upsetting the delicate balance between the standards organizations and the governments that benefit from their works.

Was the “Public Benefits” Theory of Fair Use Properly Applied in ASTM?

While the D.C. Circuit’s holding allowing the unauthorized reproduction of standards may fall within the “public benefits” line of fair use cases, in our view there is a risk that the court misjudged the interplay between standards organizations, government entities, and public access. Any challenge to the delicate symbiotic private-government relationship risks injury to the public interest, which benefits from the creation of these standards. Based on our experience working with nonprofit standards organizations for decades, we fear that the D.C. Circuit underestimated this potential disruption.

Importantly, the court found insufficient an accommodation that many standards developers (including ASTM) have already put in place in response to Public Resource’s challenge. Specifically, they have created public “reading rooms” where every standard they have developed that has been incorporated into law by reference can be read, free of charge, online in read-only mode. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) hosts an “IBR Standards Portal” offering one stop access to the incorporated by reference (IBR) standards of a dozen major standards organizations can be accessed, as well as links to another sixteen standards organizations reading rooms with links to their own IBR’d standards.

As noted, many standards organizations charge a fee for copies of their standards. In the case of many traditional standards developers, such fees comprise a major, or even the majority, of the budgets of the organizations. Developing standards is inherently time-consuming and expensive, and in some cases (e.g., organizations that develop building codes), most or all of the production of such organizations is referenced into law. In other cases, standards were never intended for referencing into law, but have been nonetheless, without notice to, or consent by, the organization that developed them. The revenues from sales and licensing are reinvested into research, development, and enhancement of new and existing standards. Respecting copyright protects the investments of these organizations in developing standards, ensuring they can fund their continuing operations and standards development and providing incentives to continue to create these essential public goods.

The unauthorized distribution by nonprofits risks reducing those revenues and incentives by offering a free alternative to purchasing or licensing the standards. This, in turn, risks slowing down the frequency of updating existing standards and innovating new ones, potentially leaving them outdated or less applicable to evolving industry needs.

This may prove to be the case if the implications of the decision extend beyond nonprofit vendors to for-profit companies. Some for-profit companies already do sell copies of standards without first paying for the rights to do so. It is difficult to see how the court’s rationale – finding fair use when a nonprofit engages in this behavior – does not extend to for-profit sales of standards.

Our bottom line takeaway: the implications of this decision on private standard-setting organizations and their business models may be far reaching. Hopefully, there may be a legislative solution that may provide relief. On March 17, 2023, Darrell Issa (R CA) introduced proposed amendments to amend the Copyright Act with bipartisan support from seven representatives from each party. If enacted, the bill would void a fair use defense against a claim of infringement of an IBR’d standard if that standard “is displayed for review in a readily accessible manner on a public website,” without cost.

We support this common sense ratification of the public reading room approach and hope that the bill is adopted.

American Society for Testing and Materials v. Public.Resource.Org., Inc. (D.C. Cir. Sept. 12, 2023).

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 28, 2023 | Copyright

In an previous post I focused on the AI “output” issue – who owns an AI model’s output? (Artificial Intelligence May Result In Human Extinction, But In the Meantime There’s a Lot of Lawyering To Be Done). I noted that this issue was pending in a lawsuit before the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia (Thaler v. Perlmutter).

The decision in this case was issued by Judge Beryl A. Howell on August 18, 2023. In her ruling Judge Howell made it clear that a creation born out of an artificial intelligence system cannot be copyrighted due to the lack of human creativity, the “sine qua non at the core of copyrightability.”

Background

In 2019 Stephen Thaler filed an unusual copyright application. Instead of a traditional artwork, the piece – titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” (the image appears at the top of this post) – identified an unusual ‘creator’ – the “Creativity Machine.” The Creativity Machine is an AI system invented by Thaler. In his application for registration Thaler informed the Copyright Office that the work was “created autonomously by machine,“ and his claim to the copyright was based on the fact of his “ownership of the machine.“

The Copyright Office, however, didn’t see it his way. Its position is that that copyright protections are reserved exclusively for works born from human ingenuity. See Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence. On this basis it declined Thaler’s application.

Judge Howell’s Decision

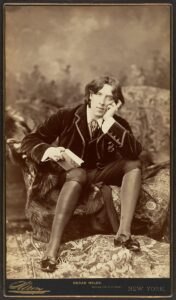

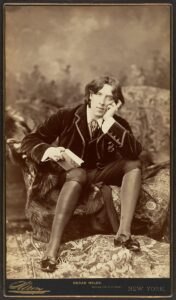

Oscar Wilde photo in Burrow-Giles case

On appeal to the district court Judge Howell acknowledged that copyright law is “malleable enough to cover works created with or involving technologies developed long after traditional media.” A prime example of this is the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1884 decision in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, holding that a photograph of Oscar Wilde was copyrightable despite use of a camera, since the camera was used to give “visible expression” to “ideas in the mind of the author.” However, the rationale in this case didn’t go far enough for Judge Howell. Her decision emphasized the foundational principle of copyright: human creativity –

The act of human creation—and how to best encourage human individuals to engage in that creation, and thereby promote science and the useful arts—[has been] central to American copyright from its very inception. Non-human actors need no incentivization with the promise of exclusive rights under United States law, and copyright was therefore not designed to reach them.

The Copyright Act itself leans heavily toward human-centric creation, with previous court decisions strengthening the court’s perspective. The case that has received much of the attention on this topic is Naruto v. Slater, where a photograph, though artistically noteworthy, wasn’t given copyright protection because it was taken by a monkey, not a human – “all animals, since they are not human,” lack standing under the Copyright Act.

Attempting to navigate this legal maze, on appeal Thaler presented a fresh angle. He argued that as the mastermind behind the AI, providing it with direction and instructions, he should be considered the rightful human author. But this theory had not been asserted in his original application for registration, and therefore was dismissed by the court: “here, plaintiff informed the register that the work was ‘created autonomously by machine,’ and his claim to the copyright was only based on the fact of his ‘ownership of the machine.'” Therefore, the court limited Thaler’s appeal to the question of whether a work generated autonomously by a computer system is eligible for copyright, and held that it was not.

Navigating Uncharted Waters: Future Implications

9th Cir in Naruto case: Monkey selfie not copyright-protected

The Thaler case sets a precedent: a creation made entirely by an AI, without human intervention, remains outside the protective bounds of the Copyright Act – at least for now. Not surprisingly, Thaler has announced that he will appeal this ruling to the D.C. Circuit. Onward and upward.

Moreover, this case leaves unaddressed a myriad of yet-to-be-answered questions:

- At what point, and to what extent – if at all – does human interaction with AI validate a creation as human-made?

- How do we gauge the originality of AI creations when these AI systems might have been trained using pre-existing works?

- Should the current structure of copyright be reformed to support and foster AI-involved creations?

These questions remain tantalizingly open, awaiting future exploration and legal interpretation. The ongoing debate about AI’s role in the world of creativity and copyright is just beginning.

Thaler v. Perlmutter (D. C. August 18, 2023)

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 15, 2023 | Copyright

A couple of people have asked me about the legal story behind Taylor Swift’s re-recording of her earlier albums.

Great question. In fact, she has re-recorded three of them.

This unusual story is a perfect “music copyright” teaching moment.

Why The Re-Recordings?

The background is a bit convoluted, but it arises out of an ugly split between Swift and her first recording company, Big Machine Records. Following the split Swift began releasing her re-recorded songs, Fearless (Taylor’s Version) and Red (Taylor’s Version) in 2021 and Speak Now (Taylor’s Version) in 2023.

Why did she re-record the songs on these albums? The gory details are discussed under the link above, but after the falling out with Big Machine, Swift decided to re-record the songs owned by it, apparently with the intention of diverting sales from her former recording company.

Swift’s popularity and financial resources allow her to do something few other artists could hope to undertake.

Copyright Law and Music

There is an important aspect of copyright law at the heart of what happened here. Every musical recording potentially has two copyrights – one in the musical work and one in each recording of the work. The musical work is the composition – the chords, melody and lyrics. Swift penned the songs on these three albums and as the author, retained ownership of these musical works. However, she assigned the recordings or “masters” to her recording company. Although she might earn royalties based on the sales and performances of these masters, she doesn’t own the copyright for them.

By not also assigning ownership of the musical works represented by the songs on the three albums, Swift retained what the music industry refers to as “publishing rights,” as in “hey, I own the publishing for this song, right?” Swift is therefore free to re-record them, as she has now done in the three “Taylor’s Version” albums.

Further Intricacies and Questions

It’s likely that there’s more to this story than has been revealed to the public. For instance, a contract between Swift and Big Machine may have temporarily delayed Swift from re-recording her songs. However, that’s more about contract law than copyright. The music industry, often a confusing maze, juggles both copyrights and contracts.

It’s likely that there’s more to this story than has been revealed to the public. For instance, a contract between Swift and Big Machine may have temporarily delayed Swift from re-recording her songs. However, that’s more about contract law than copyright. The music industry, often a confusing maze, juggles both copyrights and contracts.

The extent to which Swift is getting her hoped-for revenge is unknown – we don’t know the extent to which the re-recordings are cutting into sales of the original masters. And, no doubt there are many other legal complications that have not been made public. For example, assume a movie producer wants a “synchronization license” (a “sync” license) to use one of these recordings with a movie or TV show. The producer needs a license to both the master and the musical work. I can imagine Taylor Swift saying, “if you want a license to the musical work you need to license the new master from me as well.” This would cut out the owner of the first recording, and no doubt lead to threats of contractual interference. But is it legal? It probably is.

When I introduced the distinction between the copyrights in musical works and masters above, I said that “every musical recording potentially has two copyrights.” Why did I say “potentially”?

An example will illustrate why. Assume that in 2023 a symphony orchestra records and releases a performance of Antonín Dvořák’s NewWorld Symphony, composed in 1893. The copyright in the musical work has expired. Anyone is free to record this work. However, a new copyright applies to the new recording and will last for decades. Thus, only one copyright – the copyright in the master – exists in this scenario.

If you’re interested in the drama between Taylor Swift and her former record company, this Wikipedia entry has most of it.

Image credit: Eva Rinaldi https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taylor_Swift_%286966830273%29.jpg

by Lee Gesmer | Apr 21, 2023 | Copyright

Software copyright is an important area of copyright law. However, it has proven devilishly difficult for the courts to apply. As the Second Circuit observed 30 years ago, trying to apply copyright law to software is often an “attempt to fit the proverbial square peg in a round hole.” Judges know this – I’ll never forget the time that Massachusetts Federal District Court Judge Rya Zobel, during an initial case conference in a copyright case, looked me in the eye and said, “we aren’t going to have to compare source codes in this case, are we Mr. Gesmer?” (We didn’t, the case settled soon afterwards).

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the CAFC) has grappled with this challenge, most notably in its two controversial decisions in Oracle v. Google. (2014, 2018).

Now the CAFC has issued an important decision in SAS Institute, Inc. v. World Programming Limited (April 6, 2023; Newman dissenting). The issue in this case is one that I encountered in a copyright suit in Boston, so it’s of particular interest to me. More on that below.

SAS Institute and World Programming

SAS Institute is a successful software company. Its annual revenues exceed $3 billion, and it has more than 12,000 employees. Its statistical analysis software — the “SAS System” – is used in 3,000+ companies worldwide.

Success attracts imitation, and World Programming (now part of Altair) developed a “clone” of the SAS Software. SAS didn’t react kindly to the competition – it has conducted a more-than 10 year, multi-nation legal challenge, suing World Programming once in England and twice in the United States.

What makes SAS’s most recent copyright case against World Programming unusual is the subject matter. Most software copyright litigation involves the “literal elements” of computer programs – the “source” and “object” code – essentially the “written words” or the machine code (ones and zeros) of the software.

“Non-literal” Copyright Infringement

SAS v. World Programming, however, involved the “non-literal” elements of SAS’s system. The courts define “non-literal elements” as the structure, sequence, and organization and the user interface of software. Basically, anything other than the computer code. SAS alleged that World Programming illegally copied input syntax formats and output design styles – non-literal components of the SAS System.

The idea that non-literal components of a software program can be protected by copyright has been acknowledged since the 1980s. For the last 30 years most courts have followed the “abstraction-filtration-comparison” test (AFC test) established in the 1992 Second Circuit decision in Altai v. Computer Associates. The AFC test requires the court to (1) break a software program into its constituent parts (abstraction), (2) filter out unprotectable elements (filtration) and (3) compare the remaining protectable elements to the allegedly infringing work (comparison).

If this sounds challenging to you, you are right. However, relatively few cases have actually had to undertake the real-world application of this test to the non-literal elements of a software program. And, where they have the plaintiff has almost always lost.

The District Court Case

SAS filed this case in the Eastern District of Texas. The district court judge proceeded to apply the Altai AFC test by conducting a hearing to “filter out” unprotectable elements of the SAS software. Examples of unprotected elements include ideas, facts, information in the public domain, merger material, scènes à faire and conventional display elements. Case law has established that abstraction and filtration (steps 1 and 2 of the AFC test) is performed by the judge, not the jury.

The district court held what it termed a “copyrightability hearing” and implemented an alternating, burden-shifting framework in which SAS was required to prove a valid copyright and “factual copying.” The burden then shifted to defendant (World Programming) to prove that some or all of the copied material is unprotectable. The burden then shifted back to SAS to respond and persuade the court otherwise.

Think of this as a tennis volley in which the ball crosses the net three times.

SAS satisfied the first part of this test – it showed that it had a registered copyright, and that World Programming had copied some elements of the SAS System. However, World Programming responded with evidence that many of the non-literal components of the SAS System contained factual elements, elements that were not original to SAS or that were in the public domain, unprotected mathematical and method components, conventional display elements and merger elements. World Programming asserted that all of these components should be filtered out and excluded from step 3 of the AFC test – comparison of the two software programs.

At that point, under the judge’s burden shifting approach, the burden fell on SAS to respond and address these defenses.

Inexplicably, SAS failed to do this. The court stated –

SAS has not attempted to show what World Programming pointed to as unprotectable is indeed entitled to protection. . . . Instead, when the burden shifted back to SAS, it was clear SAS had done no filtration; they simply repeated and repeated that the SAS System was “creative.” . . . SAS’s failures have raised the untenable specter of the Court taking copyright claims to trial without any filtered showing of protectable material within the asserted work. This is not a result that this Court can condone. These failures rest solely on SAS and the consequences of those failures necessarily rest upon SAS as well.

The district court then dismissed the case. SAS appealed to the Federal Circuit – a court that is notoriously pro-copyright. (See the two Oracle decisions linked to above). SAS likely planned for any appeal to go to the Federal Circuit by asserting patent infringement against World Programming and later dropping its patent claims. Nevertheless, that was enough to give the Federal Circuit jurisdiction over any appeal.

Appeal to the Federal Circuit

On appeal the central question was procedural: Was it SAS’s burden to prove that the copied elements were protectable, or was it World Programming’s burden to prove that they were not? In other words, the issue was who bears the burden of proving, as part of the filtration analysis, that the elements the defendant copied are unprotectable – the plaintiff (copyright owner) or the defendant (alleged infringer)?

The Federal Circuit was not impressed with SAS’s arguments on appeal. It noted that rather than participate in the steps required by the Altai AFC test, SAS “failed or refused” to identify the constituent elements of the SAS software that it claimed were protectable. Instead, it argued that its software was “creative” and that it had provided evidence that World Programming had engaged in “factual copying.” But it provided no evidence in relation to the “filtration” step under the 3-part Altai AFC test.

The Federal Circuit found the trial court judge’s procedure to be appropriate: “a court may reasonably adopt an analysis to determine what the ‘core of protectable expression’ is to provide the jury with accurate elements to compare in its role of determining whether infringement has occurred.” The court concluded that SAS failed to “articulate a legally viable theory” and affirmed dismissal.

In other words, to continue the tennis analogy, SAS served the ball (showed that it had copyright registrations and that World Programming had copied some elements). World Programming returned the ball, introducing evidence that many of the elements SAS had identified were unprotected by copyright, and needed to be “filtered out” before the SAS and World Programming software programs were compared. However, SAS was unable to return that volley – “The district court found that SAS refused to engage in the filtration step and chose instead to simply argue that the SAS System was ‘creative.’”

20-20 Design v. Real View – Same Issue, No Controversy

While this is an important software copyright case and will be used defensively by copyright defendants in the future, it caught my attention for a second reason, which is that I dealt with the same issue in 20-20 Design v. Real View LLC, a copyright infringement case I tried to a jury in Boston in 2010. That case dealt with the graphical user interface of a software program – “nonliteral” elements of the software. Like World Programming in the SAS case, Real View allegedly created a “clone” program, but the cloning didn’t involve the source or object code, only parts of the graphical user interface.

Massachusetts Federal District Court Judge Patti Saris ordered 20-20 Design, the plaintiff/copyright owner, to identify the elements of its software that it claimed had been infringed. Unlike SAS, 20-20 Design complied. It provided a list of 60 elements, and the court held what Judge Saris called (by analogy) a “Markman”-style evidentiary hearing, which included evidence and testimony from experts on both sides. In effect, this was the “copyrightability hearing” held by the court in the SAS case.

Judge Saris then issued a copyrightability decision holding that almost all of the items were not individually protectible. They could, however, be protected as a “compilation.” However, she ruled that as a “compilation,” the plaintiff-copyright owner was required to prove that the defendant’s software interface was “virtually identical” – a much more difficult standard to meet than the “substantial similarity” standard applied in most copyright litigation.

(Humble brag: 20-20 Design was seeking damages of $2.8 million. However, the “virtually identical” standard proved to be its downfall. Without going into detail, suffice it to say that after a 10-day jury trial and post-trial motions the judge entered judgment for 20-20 Design against Real View (my client) in the amount of $4,200. (link)

When I read the decision in SAS v. World Programming I immediately related it to the 20-20 Design/Real View case, but I couldn’t recall how Judge Saris had allocated the burden-of-proof. When I refreshed my memory I realized why – the judge and the parties never discussed this issue. It seems that everyone assumed that the plaintiff-copyright holder (20-20 Design) had the burden of proof. After 20-20 identified the copied elements Real View argued that most of them should be filtered out and 20-20 Design (unlike SAS) responded with counter arguments. In other words, the ball went over the net three times, and the judge was able to apply the Altai AFC test and “filter” 20-20’s software before trial.

Thinking back on how smoothly this procedure went in my case, it’s difficult for me to imagine how SAS chose the strategy that cost it the World Programming case, unless this case was just an attempt to outspend a smaller competitor and drive it out of the market with litigation expenses. SAS is a multi-billion-dollar company. Its lawyers are highly experienced. Why SAS chose a case strategy that seemed doomed to failure is a bit of a mystery. One possibility is that SAS knew that if it identified the elements it would be forced into a copyright compilation theory that requires proof that the infringing work is “virtually identical” to plaintiff’s work, a burden that SAS believed it could not satisfy. Another is that it gambled that the Federal Circuit – which is notoriously protective of copyright owners – would see the law its way and reverse the district court. We will never know.

Although it remains a mystery why SAS chose a case strategy that seemed destined to fail, the SAS v. World Programming decision has important implications for software copyright law. It clarifies the burden-shifting process and emphasizes the importance that the plaintiff be fully prepared to engage in the Altai AFC test’s filtration step.

Will SAS appeal this decision to the Supreme Court? Given the resources that SAS has dedicated to its litigation with World Programming over the last decade it seems likely that it will. While I view it as doubtful that the Supreme Court will hear this case, you never know.

SAS Institute v. World Programming (Fed. Cir. April 6, 2023)

by Lee Gesmer | Mar 6, 2023 | Copyright

There are a number of computer programs and websites that will allow you to create an image using artificial intelligence. One of them is Midjourney. You can see some of the Midjourney AI-generated art here.

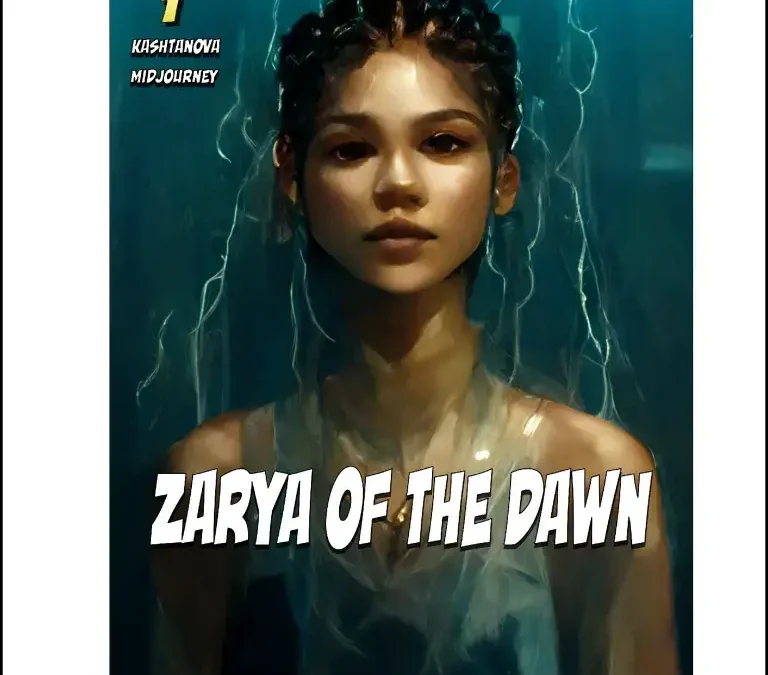

Kris Kashtanova used Midjourney’s generative AI tool to create a comic book titled Zarya of the Dawn. She submitted the work to the Copyright Office, seeking registration, and the Office issued the registration in September 2022. However according to the Copyright Office Ms. Kashtanova did not disclose that she used artificial intelligence to create Zarya.

Soon afterwards the Office became aware – via a reporter’s inquiry and social media posts – that Ms. Kashtanova had created the comic book using artificial intelligence. The Office reconsidered the registration and, after much correspondence and argumentation with Ms. Kashtanova’s attorneys, canceled the registration, concluding that:

. . . the images in the Work that were generated by the Midjourney technology are not the product of human authorship. Because the current registration for the Work does not disclaim its Midjourney-generated content, we intend to cancel the original certificate issued to Ms. Kashtanova and issue a new one covering only the expressive material that she created.

Image from Zarya

This conclusion is the denouement in a lengthy letter from the Copyright Office analyzing the copyrightability of the images contained in the Zarya comic in detail in light of how Midjourney creates images. In correspondence with the Copyright Office Ms. Kashtanova argued that she had provided “hundreds or thousands of descriptive prompts” to Midjourney to generate “as perfect a rendition of her vision as possible.” However, based on how Midjourney creates images – essentially via a random mechanical process, notwithstanding the prompts of the human “mastermind” – the Copyright Office concluded that she was not the “author” of the resulting images for copyright purposes. The Copyright Office reasoned that “unlike other tools used by artists” (such as Adobe Photoshop), Midjourney generates images using prompts in an “unpredictable way.” “Because of the significant distance between what a user may direct Midjourney to create and the visual material Midjourney actually produces,” Ms. Kashtanova did not have enough control over the final images generated to be the “inventive or mastermind” behind the images.

Here are some takeaways from this decision.

First, artists using generative AI to create images should not assume that they own a copyright in the images. At present the Copyright Office appears firmly committed to its position that they do not, and until there are court decisions to the contrary, or Congress amends the Copyright Act to accommodate these works, the better practice is to assume no protection.

Second, it may be possible to protect an AI-created work based on human modifications to the work. This was illustrated by the Zarya decision, where Ms. Kashtanova also sought registration for images that she created using Midjourney but altered post-production using Photoshop. With respect to one of these images the Copyright Office left open the possibility that copyrightable expression had been added, and therefore the image might receive registration. However, in these cases the burden will be on the human artist to establish that the human modifications or contributions reflect sufficient expression to receive protection. And, the scope of protection would likely be limited to the modifications, not the full image.

Image from Zarya

Third, this is a fast-moving area of law. Ms. Kashtanova – or any person or company denied registration – has the right to appeal the Copyright Office’s decision to a federal district court, from which the case may go on appeal to a circuit court, or even the Supreme Court. Whether Ms Kashtanova will take that action – or whether we will have to wait for another case – remains to be seen. A court – or Congress by amendment to the Copyright Act – could change the law on copyright protection of AI images.

Lastly, the Copyright Office’s reasoning on AI images is likely to extend to text as well. Thus, if a person uses a program such as ChatGPT to create a written work, it seems unlikely that the Copyright Office would accept it for purposes of registration. Despite the best efforts of the “prompt engineer,” the resulting output is likely to be too random to fall within the Copyright Office’s views of authorship.

Update: On March 10, 2023, less than a week after I published this post, the Copyright Office issued a “statement of policy to clarify its practices for examining and registering works that contain material generated by the use of artificial intelligence technology.” (link). Here is the heart of that policy statement: “In the case of works containing AI-generated material, the Office will consider whether the AI contributions are the result of ‘mechanical reproduction’ or instead of an author’s ‘own original mental conception, to which [the author] gave visible form.’ The answer will depend on the circumstances, particularly how the AI tool operates and how it was used to create the final work. This is necessarily a case-by-case inquiry.”

How this principle will be applied in practice remains to be seen.

by Lee Gesmer | Sep 3, 2022 | Copyright

With some exceptions, every public venue that plays popular music for its customers – concert venue, bar, restaurant, shopping mall or health club – needs to enter into a blanket license agreement with ASCAP, BMI and SESAC, the performing rights organizations (PROs) that pay public performance royalties to songwriters and publishers.

Occasionally a club will fail to join a PRO, ignore warnings and be sued for copyright infringement.

Here’s a current example in which a club did sign a license with ASCAP, but allegedly failed to pay ASCAP the license fees.

Universal Music v. Calvin Theater

Two music publishers have sued Calvin Theater and its owner/manager, Eric Suher, for violating public performance rights in six compositions. Calvin Theater is a music venue in Northampton, Massachusetts, and the suit was filed in the Federal District Court for the District of Massachusetts. ASCAP manages the public performance rights for these songs.

District of Massachusetts. ASCAP manages the public performance rights for these songs.

We don’t know why Calvin Theater failed to pay ASCAP. However, the publishers’ claim is that because the venue is in breach the agreement is not in effect and the Theater has no copyright license.

Based on the allegations in the complaint this case is a good opportunity to do a short tutorial on the intersection of the music industry and copyright law.

The Infringement Involves “Musical Compositions,” Not “Sound Recordings”

Every musical work can have two copyrights – the musical composition (melody, lyrics) and the sound recording. The owners can be different, and usually are – it’s common for a record company to own the copyright in the “master” sound recording and a publishing company to own rights in the musical composition.

Calvin Theater involves the public performance of musical compositions – there is no allegation that sound recordings were illegally copied. The complaint doesn’t identify the owner of the sound recordings, nor does it need to do so.

The complaint doesn’t provide any detail about how the compositions were performed. Were the works performed by a live band? Did the Calvin Theater play a CD or stream the songs? Were the songs played over a radio? Which versions of the songs were played – the originals or cover recordings? The complaint doesn’t tell us, but it doesn’t matter – regardless of how the songs were played, the owners of the copyrights in the musical compositions are entitled to a public performance royalty. The music club should have paid that through a contract with ASCAP.

What Is The Right of Public Performance?

One of the exclusive rights held by owners of musical compositions is the right to publicly perform a work. The Copyright Act defines public performance broadly – “to perform … at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered.”

If a public venue plays popular music for its customers, it needs a public performance license. If it plays music and doesn’t have one, it’s a copyright infringer.

If you’re wondering about the public performance rights of owners of sound recordings – they don’t have one, except for digital audio transmissions. 17 U.S. Code § 106

What Are Publishing Companies?

The plaintiffs in this case are publishing companies. What’s that, you ask?

A lot of composers don’t have the time or inclination to deal with the music business. Instead, they assign ownership of their compositions to a publishing company to manage. There are many publishing companies, and the largest own publishing rights to thousands of songs. Two large publishers are the two plaintiffs in this case – Universal Music Publishing and Primary Wave.

to a publishing company to manage. There are many publishing companies, and the largest own publishing rights to thousands of songs. Two large publishers are the two plaintiffs in this case – Universal Music Publishing and Primary Wave.

What Are Performing Rights Organizations?

The owners of compositions – whether publishing companies or the composers themselves – can’t track and police the thousands of public venues where their compositions may be performed. A complex system has evolved to deal with this – they register their compositions with one of the PROs – ASCAP, BMI or SESAC. In turn, the PROs enter into blanket license agreements with the clubs and restaurants.

The clubs pay the PROs, the PROs pay the publishing companies, and the publishing companies pay the composers. This is all regulated by contracts – thousands and thousands of contracts.

It’s even more complicated than it sounds. For a deeper dive see Songtrust’s “Modern Guide to Music Publishing.“

The Publishing Companies Are Assignees of the Publishing Rights

The two plaintiffs in this case allege that they are owners of the six compositions that have been infringed. From this we know that the composers have transferred ownership of the compositions to these companies. The publishers must be either owners or exclusive licensees to bring a copyright infringement lawsuit.

to bring a copyright infringement lawsuit.

Both publishers are members of ASCAP. In order to avoid infringing the compositions of these songs, Calvin Theater needed to enter into a blanket license agreement with ASCAP and not breach the agreement.

The Owner of the Club May be Personally Liable

The complaint alleges that Eric Suher is an owner, officer and director of Calvin Theater, that he controls, manages and operates the company that owns the club, and that he has the right and ability to supervise and control the public performance of musical compositions at the club.

This is important – in my experience many lawyers and business owners don’t realize that a corporation may not shield a business owner or manager from personal liability for copyright infringement. For details on why this may be the case, see Redigi – Did Ossenmacher Know He Was Risking Personal Liability?

If the publishers win their case Suher and Calvin Theater may be jointly and severally liable for copyright infringement.

The Works Are Registered

To bring a claim of copyright infringement a work must be registered. This was uncertain until 2019, when the Supreme Court decided Fourth Estate Public Benefit Corp. v. Wall-Street.com, LLC. Before that some courts held that a pending registration was sufficient.

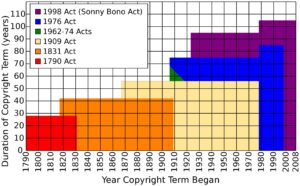

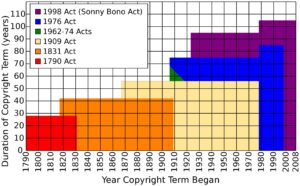

Here the publishers provided the registration numbers and dates for each registration. The compositions were initially registered in the early/mid-1970s. None of the copyrights have expired. In fact, the composers are still alive, so the copyrights will remain in effect for at least another 70 years. Even though the copyrights have been transferred, their duration continues to follow the lives of the composers.

early/mid-1970s. None of the copyrights have expired. In fact, the composers are still alive, so the copyrights will remain in effect for at least another 70 years. Even though the copyrights have been transferred, their duration continues to follow the lives of the composers.

The Publishers Are Seeking Statutory Damages

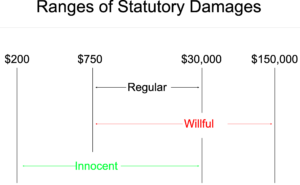

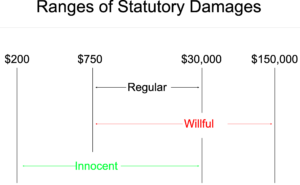

The publishers don’t want actual damages (their lost profits) or the club’s profits attributable to the infringement – these are probably minimal. The publishers have asked for statutory damages of between $750 and $30,000 per infringing work.

Because the registrations preceded the infringements (which took place in 2022), they are entitled to seek statutory damages and, at the discretion of the judge, attorney’s fees.

However, the amount they are seeking is worth questioning – when an infringement is “willful” statutory damages may be as high as $150,000 per work infringed – in this case that would total $900,000. The publishers allege that ASCAP repeatedly told Calvin Theater that it was infringing and demanded that the Theater pay the contractual license fees. It’s not clear why the publishers are not seeking $150,000 per work based on what appears, at least for pleading purposes, to have been willful infringement.

That said, statutory damages are complicated. This table illustrates the options, depending on whether an infringement is “innocent,” “regular” or “willful”:

Conclusion

If the allegations are true this is a straightforward case. It illustrates the elements of a copyright case in the music industry, and how much trouble a public venue can get into by ignoring the requirement that it license rights from the performing rights organizations if it’s going to play popular music.

However, music publishers are not in business to force music venues into bankruptcy. Most likely Calvin Theater’s lawyers will tell their client that it should settle, and the publishers will accept reasonable terms. I’ll keep an eye on the case and update this post if that happens.

Update: The case was dismissed in December 2022. Very likely the dismissal was pursuant to a settlement.

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 22, 2022 | Copyright

The doctrine of fair use has been called, with some justification, the most troublesome in the whole law of copyright. Justice Blackmun. Sony v. Universal (1984)

Fair use in America simply means the right to hire a lawyer. Larry Lessig

Fair use is the great white whale of American copyright law. Enthralling, enigmatic, protean, it endlessly fascinates us even as it defeats our every attempt to subdue it. Prof. Paul Goldstein

*********

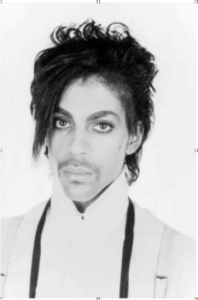

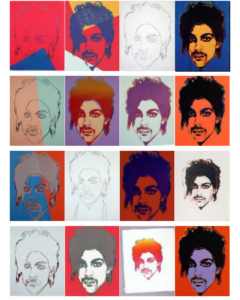

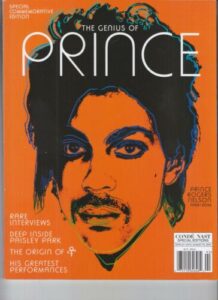

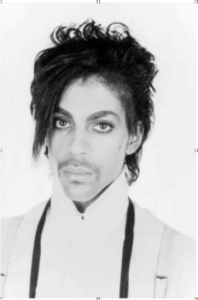

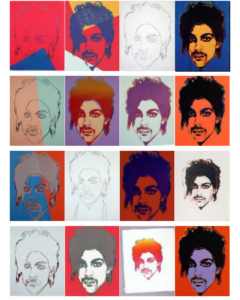

The photo of Prince directly below was taken by Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. Andy Warhol used this photo to create an unauthorized series of sixteen silkscreens and drawings – the “Prince Series” – which appears below Goldsmith’s photo.

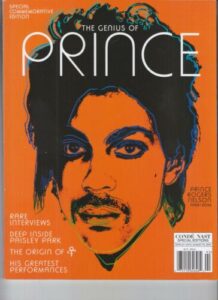

Conde Nast Cover

Goldsmith is a well-known rock-and-roll celebrity photographer. When Warhol passed away in 1987 the Prince Series became the property of the Warhol Foundation. Goldsmith was unaware of its existence until Condé Nast licensed one of the silkscreens for the cover of a Prince tribute magazine following Prince’s death in 2016. When Goldsmith learned that Warhol had copied her photo she sued the Warhol Foundation for copyright infringement.

Warhol’s defense in Goldsmith’s case is fair use – specifically the “transformative” branch of copyright fair use. This has its origin in Campbell v. Accuf-Rose, a 1994 case involving a parody of Roy Orbison’s song “Pretty Woman.” The Supreme Court held that a new work of art is “transformative” for purposes of copyright fair use if it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.”

This legal standard has proven to be subjective and inconsistent in its application. The Warhol case is a good example.

The District Court and Second Circuit Decisions in Warhol

A Southern District of New York district court judge agreed with Warhol’s defense that the Prince Series was “transformative.” The judge reasoned that while Goldsmith’s photo portrays Prince as “not a comfortable person” and a “vulnerable human being,” the Prince Series portrays the musician as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.” Comparing the works side-by-side, the district court concluded that a reasonable observer would perceive that Warhol’s work has a “different character, a new expression, and employs new aesthetics with [distinct] creative and communicative results” when compared to the Goldsmith original.

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed. It held that to satisfy the “transformative” requirement the second work (the Warhol Series) must –

. . . at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work such that the secondary work remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material. The judge must examine whether the secondary work’s use of its source material is in service of a fundamentally different and new artistic purpose and character, such that the secondary work stands apart from the raw material used to create it.

In the eyes of the Second Circuit Warhol’s silkscreens failed this test. Hence, they were not protected by fair use.

Interest in the case has been high since the Second Circuit issued its decision last year. It increased when the Supreme Court agreed to hear Warhol’s appeal, and has gone into overdrive as the case approaches oral argument on October 12, 2022. Warhol filed its appeal brief in early June. Goldsmith filed her opposition in early August. More than 30 amicus briefs have been filed. The Copyright Office and the Solicitor General have filed an amicus brief in support of Goldsmith, and the Solicitor General has asked for leave to participate at oral argument.

Google v. Oracle: Will It Matter to the Warhol Appeal?

An important consideration is how the Court’s 2021 ruling in Google v. Oracle may impact this case. Google is only the second time the Supreme Court has addressed fair use in depth. However, while the Court upheld Google’s fair use defense, the subject of that case was far from the traditional core of copyright – visual art, music and writings. Google involved fair use in the context of Google’s copying and reimplementation of Oracle’s Java API user interface. The Court found this to be fair use because it was socially beneficial – it allowed programmers familiar with the Java API to use their knowledge and experience to program Google’s Android operating system, rather than having to learn a new API. See Final Thoughts On Google v. Oracle.

Warhol argued that Google helped tip the scales in its favor, but the Second Circuit rejected this argument, stating that “a case that addresses fair use in such a novel and unusual context [as functional computer programs] is unlikely to work a dramatic change in the analysis of established principles as applied to a traditional area of copyrighted artistic expression.”

Will the Supreme Court affirm or reverse the Second Circuit? Setting aside Google (which is something of a one-off for copyright fair use), this is only the second time the Court will have addressed fair use since 1994 – will the Court expand fair use (by reversing the Second Circuit), contract it or tread lightly and leave it largely intact?

In pondering these questions it’s worth noting that changes in the Court’s make-up may be a significant factor in the outcome of this case.

Fair Use at the Supreme Court Without Justice Breyer

Until his retirement in June 2022 Justice Breyer had focused on intellectual property law more than any other member of the Court. He was viewed as the most liberal justice on IP issues, and he wrote the majority pro-fair use decision in Google.

Given the current make-up of the Court post-Breyer, a little armchair kremlinology is in order.

Based on their dissent in Google it seems likely that Justices Thomas and Alito will vote to uphold the Second Circuit’s decision for Goldsmith. Under their view of fair use the most important factor is the effect of Warhol’s silkscreens on the market for Goldsmith’s photo. (Google, p. 1216). The Second Circuit found that Warhol’s silkscreens negatively impacted the market for Goldsmith’s original photo in a variety of ways, and Justices Thomas and Alito are likely to overweight this factor in concluding that Warhol’s silkscreens are not protected by fair use.

The remaining justices on the new “conservative” wing of the Court – Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett – favor “textualism,” the judicial philosophy that places primary weight on the normal meanings of a statute’s words, rather than public policy. It’s worth noting that the word “transformative” (indeed, the concept) appears nowhere in the Copyright Act, and is something of a judicial gloss on the statutory enumerated fair use factors. Based on a strict application of textualism these three justices may side with Justice Thomas’s view of fair use, in which case the Warhol Foundation will lose its bid to reverse the Second Circuit 5-4. If “swing conservative” Chief Justice Roberts joins the conservative wing, Warhol will lose at least 6-3.

My prediction: the Second Circuit’s ruling in favor of Lynn Goldsmith will be affirmed by at least a 5-4 vote.

Conclusion

Either way, affirm or reverse, will this case change fair use in the U.S.? We won’t know until the Supreme Court issues its decision, likely sometime in 2023. In the meantime, tune in to the oral argument in October and judge for yourself.

Update 5-18-23: I was correct in predicting that the Court would uphold the Second Circuit in this case. Here is the 7-2 decision – link

by Lee Gesmer | Apr 27, 2022 | Copyright

If you own or manage a website you may be familiar with the process of “photo embedding” or “inline linking” an image or video on your site. Rather than hosting the image file on your own server you retrieve the image from another Internet site and embed the content as part of your webpage’s overall display. Users can’t tell the difference, but as a technical (and legal) matter you never “copy” the image to your server.

This practice is common, and has been performed millions of times on millions of sites. You have no legal concerns since you’re just channeling the image from another site. No worries, right?

Not so fast. This is actually a hotly disputed legal issue in the world of digital copyright.

For many years there actually were no worries. Way back in 2007 the Ninth Circuit created what has come to be called the “server test” in Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc. This gave unauthorized embedding a legal green light so long as the image resided on another server. In copyright lingo the embedding site does not host any “material objects … in which a work is fixed … and from which the work can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated” and thus does not communicate a copy. 17 U.S.C. § 101.

However, in addition to the right of reproduction the Copyright Act gives the owner of a work the right of public display – copyright owners have the exclusive right to “transmit or otherwise communicate… a display of the work… to the public, by means of any device or process.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. The Ninth Circuit used similar reasoning to hold that an image is not displayed when the embedding site’s computer does not store the photographic images.

For many years the “server test” has been shaky but accepted law. A few courts around the country suggested that the Ninth Circuit’s holding that unauthorized embedding didn’t constitute public display was questionable, but there were no clear rulings on this issue.

However, in the recent decision in McGucken v. Newsweek LLC (S.D. N.Y. March 21, 2022) a federal district court in the southern district of New York (the “SDNY”) outright rejected this rule in a case in which Newsweek embedded a photographer’s Instagram post in an online news article without his permission. The court focused on the right of display and concluded that –

After all, the Copyright Act defines “display” as “to show a copy of” a work, 17 U.S.C. § 101, and not “to make and then show a copy of the copyrighted work.” . . . The Ninth Circuit’s approach, under which no display is possible unless the alleged infringer has also stored a copy of the work on the infringer’s computer, would seem to make the display right merely a subset of the reproduction right. . . . The Copyright Act makes clear, however, that to “show a copy” is to display it. . . . Therefore, the Court finds that Defendant did in fact display Plaintiff’s Photograph when it embedded the Photograph in the Article.

In fact, this is the second time an SDNY court has reached this conclusion. In Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, LLC (2018) the district court held that an embedded tweet violated the photographer-plaintiff’s right of public display: “the plain language of the Copyright Act . . . provides no basis for a rule that allows the physical location or possession of an image to determine who may or may not have ‘displayed’ a work within the meaning of the Copyright Act.” (See my earlier post, Is In-Line Linking Illegal Now?).

However, in Goldman the Second Circuit denied interlocutory review and the case settled before any appeal. Hence, the issue didn’t reach the Second Circuit in that case.

The split between the Ninth Circuit and the trial courts in the southern district of New York leaves website owners with a difficult decision – do they assume that Ninth Circuit law is controlling, and therefore continue to embed images? Clearly, for trial judges in SDNY the answer is “no” – these courts, at least, have made clear that they view this practice to be a violation of the right of public display. And, since a copyright plaintiff can often engage in “forum shopping” and file a copyright suit in that district the only safe conclusion is that this practice should be avoided nationwide, at least until one of the southern district cases reaches the Second Circuit on appeal and the split between the SDNY and the Ninth Circuit is resolved. If the Second Circuit creates a circuit split with the Ninth Circuit at the appellate level, the issue would be ripe for Supreme Court review.

There is another dimension to this issue that bears mentioning: the copyright issues are intertwined with complex terms, conditions and technical measures imposed by photo hosting services.

The poster child for this is Instagram. Instagram is the most popular source of images for embedded images, and it facilitates embedding by providing an embedding API. Late last year Instagram introduced a new feature allowing copyright owners to disable the embedding feature for photos they post. Before that, Instagram posters had to elect to use a private account to block unwanted embedding.