A couple of people have asked me about the legal story behind Taylor Swift’s re-recording of her earlier albums.

Great question. In fact, she has re-recorded three of them.

This unusual story is a perfect “music copyright” teaching moment.

Why The Re-Recordings?

The background is a bit convoluted, but it arises out of an ugly split between Swift and her first recording company, Big Machine Records. Following the split Swift began releasing her re-recorded songs, Fearless (Taylor’s Version) and Red (Taylor’s Version) in 2021 and Speak Now (Taylor’s Version) in 2023.

Why did she re-record the songs on these albums? The gory details are discussed under the link above, but after the falling out with Big Machine, Swift decided to re-record the songs owned by it, apparently with the intention of diverting sales from her former recording company.

Swift’s popularity and financial resources allow her to do something few other artists could hope to undertake.

Copyright Law and Music

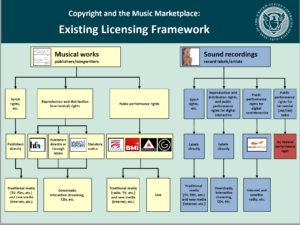

There is an important aspect of copyright law at the heart of what happened here. Every musical recording potentially has two copyrights – one in the musical work and one in each recording of the work. The musical work is the composition – the chords, melody and lyrics. Swift penned the songs on these three albums and as the author, retained ownership of these musical works. However, she assigned the recordings or “masters” to her recording company. Although she might earn royalties based on the sales and performances of these masters, she doesn’t own the copyright for them.

By not also assigning ownership of the musical works represented by the songs on the three albums, Swift retained what the music industry refers to as “publishing rights,” as in “hey, I own the publishing for this song, right?” Swift is therefore free to re-record them, as she has now done in the three “Taylor’s Version” albums.

Further Intricacies and Questions

It’s likely that there’s more to this story than has been revealed to the public. For instance, a contract between Swift and Big Machine may have temporarily delayed Swift from re-recording her songs. However, that’s more about contract law than copyright. The music industry, often a confusing maze, juggles both copyrights and contracts.

It’s likely that there’s more to this story than has been revealed to the public. For instance, a contract between Swift and Big Machine may have temporarily delayed Swift from re-recording her songs. However, that’s more about contract law than copyright. The music industry, often a confusing maze, juggles both copyrights and contracts.

The extent to which Swift is getting her hoped-for revenge is unknown – we don’t know the extent to which the re-recordings are cutting into sales of the original masters. And, no doubt there are many other legal complications that have not been made public. For example, assume a movie producer wants a “synchronization license” (a “sync” license) to use one of these recordings with a movie or TV show. The producer needs a license to both the master and the musical work. I can imagine Taylor Swift saying, “if you want a license to the musical work you need to license the new master from me as well.” This would cut out the owner of the first recording, and no doubt lead to threats of contractual interference. But is it legal? It probably is.

When I introduced the distinction between the copyrights in musical works and masters above, I said that “every musical recording potentially has two copyrights.” Why did I say “potentially”?

An example will illustrate why. Assume that in 2023 a symphony orchestra records and releases a performance of Antonín Dvořák’s NewWorld Symphony, composed in 1893. The copyright in the musical work has expired. Anyone is free to record this work. However, a new copyright applies to the new recording and will last for decades. Thus, only one copyright – the copyright in the master – exists in this scenario.

If you’re interested in the drama between Taylor Swift and her former record company, this Wikipedia entry has most of it.

Image credit: Eva Rinaldi https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taylor_Swift_%286966830273%29.jpg