by Lee Gesmer | Jul 8, 2025 | Copyright, DMCA/CDA

The recent blockbuster decisions in Bartz v. Anthropic and Kadrey v. Meta have raised a number of important and controversial issues. On the facts, both cases held that using copyright-protected works to train large language models was fair use.

Still, AI industry executives shouldn’t be too quick to celebrate. Bartz held that Anthropic is liable for creating a library of millions of works downloaded illegally from “shadow libraries,” and it could be facing hundreds of millions of dollars in class-action damages. And, as I discuss here, Kadrey argued for a new theory of copyright fair use that, if adopted by other courts, could have a significant negative impact on generative AI innovation.

Both cases were decided on summary judgment by judges in the Northern District of California. Bartz was decided by Judge William Alsup; Kadrey was decided by Judge Vince Chhabria. However, the two judges took dramatically different views of copyright fair use.

Judge Chhabria set the stage for his position as follows:

Companies are presently racing to develop generative artificial intelligence models—software products that are capable of generating text, images, videos, or sound based on materials they’ve previously been “trained” on. Because the performance of a generative AI model depends on the amount and quality of data it absorbs as part of its training, companies have been unable to resist the temptation to feed copyright-protected materials into their models—without getting permission from the copyright holders or paying them for the right to use their works for this purpose. This case presents the question whether such conduct is illegal.

Although the devil is in the details, in most cases the answer will likely be yes.

Did a federal judge really just say that in most cases using copyrighted works to train AI models without permission is illegal? Indeed he did.

Let’s unpack.

Market Dilution – A New Fair Use Doctrine?

Judge Chhabria’s rationale is that generative-AI systems “have the potential to flood the market with endless amounts of images, songs, articles, books, and more,” produced “using a tiny fraction of the time and creativity” human authors must invest. From that premise he derived a new variant of factor-four fair use analysis – “market dilution,” the idea that training an LLM on copyrighted books can harm authors even when the model never regurgitates their prose. It does so, he says, by empowering third parties to saturate the market with close-enough substitutes.

Copyright law evaluates fair use by weighing the four factors identified in the copyright statute. Factors one and four are often the most important. Factor one asks whether the use is “transformative.” Judge Chhabria had no difficulty concluding (as did Judge Alsup in Bratz), that the purpose of Meta’s copying – to train its LLMs – was “highly transformative.”

Factor four looks at “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work,” and Judge Chhabria’s analysis focused on this factor.

Judge Chhabria reasoned that because an LLM can “generate literally millions of secondary works, with a minuscule fraction of the time and creativity used to create the original works it was trained on,” no earlier technology poses a comparable threat; therefore “the concept of market dilution becomes highly relevant.” Judge Chhabria stressed that the harm he fears is not piracy but indirect substitution: readers who pick an AI-generated thriller or gardening guide instead of a mid-list human title, thereby depressing sales and, with them, the incentive to create.

Judge Chhabria recognized that the impact on works other than text (all that was at issue in the case before him) could be even greater: “this effect also seems likely to be more pronounced with respect to certain types of works. For instance, an AI model that can generate high-quality images at will might be expected to greatly affect the market for such images, diminishing the incentive for humans to create them.” Although Judge Chhabria didn’t mention it, music is already suffering from AI-generated music.

A Solitary Theory – So Far

Judge Chhabria acknowledged that “no previous case has involved a use that is both as transformative and as capable of diluting the market for the original works as LLM training is.” Courts have often considered lost sales from non-literal substitutes, but always tethered to copying and similarity. By contrast, “dilution” here is the main event: infringement-adjacent competition, scaled up by algorithms, becomes dispositive even where every output may be dissimilar and lawful. That outlook has no counterpart in the copyright statute or prior case law.

Why the Plaintiffs Still Lost

However, a novel legal theory does not excuse absent proof. The thirteen authors in Bartz “never so much as mentioned [dilution] in their complaint,” offered no expert analysis of Llama-driven sales erosion, and relied chiefly on press reports of AI novels “flooding Amazon.” Meta, meanwhile, produced data showing its model’s launch left the plaintiff’s sales untouched. Speculation, Judge Chhabria concluded, “is insufficient to raise a genuine issue of fact and defeat summary judgment.” The court elevated market dilution to center stage and then ruled against the plaintiffs for failing to prove it.

The Evidentiary Gauntlet Ahead

Judge Chhabria’s opinion outlines what future litigants will have to supply to prove dilution. They must demonstrate that the defendant’s specific model can and will produce full-length works in the same genre; that those works reach the market at scale; that readers choose them instead of the plaintiff’s title; that the competitive edge flows from exposure to the plaintiff’s expression rather than public-domain material; and that the effect is measurable through sales data, price trends or other empirical evidence. Each link is contestable, and the chain grows longer as AI models add safety rails or licensing pools. The judge’s warning that “market dilution will often cause plaintiffs to decisively win the fourth factor—and thus win the fair use question overall,” may prove to be true, but the proof he demands for this is nothing short of monumental.

Policy Doubts

Judge Chhabria’s dilution theory invites several critiques. First, it risks administrative chaos: judges will referee dueling experts over how similar, how numerous and over what time period AI outputs must be considered before they count as substitutes. Second, it blurs the line between legitimate innovation and liability; many technologies have lowered creative barriers without triggering copyright damages simply for “making art easier.” Third, it revives the circularity the Supreme Court warned against in Google v. Oracle: the rightsholder defines a market (“licensing my book for AI training”) and then claims harm because no fee was paid, a logic the judge himself rejects elsewhere in the opinion. Such broad-brush dangers may be better handled, if at all, by statutory solutions – collective licensing or compulsory schemes – than by case-by-case fair-use adjudication.

A Split Already Emerging

Two days before Kadrey, Judge William Alsup faced similar facts in Bartz v. Anthropic and dismissed dilution as nothing more than teaching “schoolchildren to write well,” an analogy he said posed “no competitive or creative displacement that concerns the Copyright Act.” Judge Chhabria rebuts that comparison as “inapt,” pointing to an LLM’s capacity to let one user mass-produce commercial text. This internal split in the Northern District is an early signal that the Ninth Circuit, the Supreme Court, and perhaps even Congress, will need to clarify the law.

Practical Takeaways

For authors contemplating suit based on a dilution theory Kadrey offers both hope and the challenge of proof. To meet the challenge plaintiffs must plead dilution explicitly. Retain economists early. Collect Amazon ranking histories, royalty statements, and genre-level sales curves. Show, with numbers, how AI thrillers or gardening guides cannibalize their human counterparts. AI Defendants, in turn, should preserve training-data logs, document output filters, and press for causation: proof that their model, not the zeitgeist, dented the plaintiff’s revenue. Until one side clears the evidentiary bar, most LLM cases will continue to rise or fall on traditional substitution and lost-license theories.

But whether “market dilution” becomes a real threat to AI companies or stands alone as a curiosity depends on whether other courts embrace it. With over 40 copyright cases against generative AI developers now winding through the courts, we shouldn’t have to wait long to see if Judge Chhabria’s dilution theory was the first step toward a new copyright doctrine or a one-off detour.

The Bottom Line

Despite Judge Chhabria’s warning that most unauthorized genAI training will be illegal, Kadrey v. Meta is not the death knell for AI training; it is a judicial thought experiment that became dicta for want of evidence. “Market dilution” may yet find a court that will apply it and a plaintiff who can prove it. Until then, it remains intriguing, provocative, and very much alone. Should an appellate court embrace the theory, the balance of power between AI developers and authors could tilt markedly. Should it reject the theory, Kadrey will stand as a cautionary tale about stretching fair use rhetoric beyond the record before the court.

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 23, 2025 | Contracts, Copyright, DMCA/CDA

At the heart of large language model (LLM) technology lies a deceptively simple triad: compute, algorithms, and data.

Compute powers training – vast arrays of graphics processing units crunching numbers at a scale measured in billions of parameters and trillions of tokens. Algorithms shape the intelligence – breakthroughs like the Transformer architecture enable models to understand, predict, and generate human-like text. Data is the raw material, the fuel that teaches the models everything they know about the world.

While compute and algorithms continue to advance at breakneck speed, data has emerged as a critical bottleneck. Training a powerful LLM requires unimaginably large volumes of text, and the web’s low-hanging fruit – books, Wikipedia, forums, blogs – has largely been harvested.

The large AI companies have gone to extraordinary lengths to collect new data. For example, Meta allegedly used bittorrent to download massive amounts of copyrighted content. OpenAI reportedly transcribed over a million hours of Youtube videos to train its models. Despite this, the industry may be approaching a data ceiling.

In this context, Reddit represents an unharvested goldmine – a sprawling archive containing terabytes of linguistically rich user-generated content.

And, according to Reddit, Anthropic, desperate for training data, couldn’t resist the temptation: it illegally scraped Reddit without a license and trained Claude on Reddit data.

The Strategic Calculus: Why Contract, Not Copyright

Reddit filed suit against Anthropic in San Francisco Superior Court on June 4, 2025. However, it chose not to follow the well-trodden path of federal copyright litigation in favor of a novel contract-centric strategy. This tactical pivot from The New York Times Co. v. OpenAI and similar copyright-based challenges signals a fundamental shift in how platforms may assert control over their data assets.

Reddit’s decision to anchor its complaint in state contract law reflects the limitations of copyright doctrine and the structural realities of user-generated content platforms. Unlike traditional media companies that own their content outright, Reddit operates under a licensing model where individual users retain copyright ownership while granting the platform non-exclusive rights under Section 5 of its User Agreement.

This ownership structure creates obstacles for copyright enforcement at scale. Reddit would face complex Article III standing challenges, since it lacks the requisite ownership interest to sue for direct infringement. Moreover, the copyright registration requirements (a precondition to filing suit) would prove prohibitively expensive and logistically impossible for millions of user posts. And, even if Reddit could establish standing, it would face the copyright fair use defenses that have been raised in the more than 40 pending AI copyright cases.

requisite ownership interest to sue for direct infringement. Moreover, the copyright registration requirements (a precondition to filing suit) would prove prohibitively expensive and logistically impossible for millions of user posts. And, even if Reddit could establish standing, it would face the copyright fair use defenses that have been raised in the more than 40 pending AI copyright cases.

By pivoting to contract law, Reddit sidesteps these constraints. Contract claims require neither content ownership nor copyright registration – only proof of agreement formation and breach.

The Technical Architecture of Alleged Infringement

Reddit’s complaint alleges that Anthropic’s bot made over 100,000 automated requests after July 2024, when Anthropic publicly announced it had ceased crawling Reddit. This timeline is significant because it suggests deliberate circumvention of robots.txt exclusion protocols and platform-specific blocking mechanisms.

According to Reddit, the technical details reveal sophisticated evasion tactics. Unlike legitimate web crawlers that respect robots.txt directives, the alleged “ClaudeBot” activity employed distributed request patterns designed to avoid detection. Reddit’s complaint specifically references CDN bandwidth costs and engineering resources consumed by this traffic – technical details that will be crucial for establishing the “impairment” element required under California’s trespass to chattels doctrine.

The complaint’s emphasis on Anthropic’s “whitelist” of high-quality subreddits demonstrates technical sophistication in data curation. This selective approach undermines any defense that the scraping was merely incidental web browsing, instead revealing a targeted data extraction operation designed to maximize training value while minimizing detection risk.

Here’s a quick look at the three strongest counts in Reddit’s complaint: breach of contract, trespass to chattels and unjust enrichment.

Browse-Wrap Formation: The Achilles’ Heel

The most vulnerable aspect of Reddit’s contract theory lies in contract formation under browse-wrap principles. Reddit argues that each automated request constitutes acceptance of its User Agreement terms, which prohibit commercial exploitation under Section 3 and automated data collection under Section 7.

However, under Ninth Circuit precedent applying California law, browse-wrap contracts require reasonably conspicuous notice, and Reddit’s User Agreement link appears in small text at the page footer without prominent placement or mandatory acknowledgment – what some courts have termed “inquiry notice” rather than “actual notice.”

And, unlike human users who might scroll past terms of service, automated bots often access content endpoints directly, without rendering full page layouts. This raises fundamental questions about whether algorithmic agents can form contractual intent under traditional offer-and-acceptance doctrine.

This raises fundamental questions about whether algorithmic agents can form contractual intent under traditional offer-and-acceptance doctrine.

California courts have been increasingly skeptical of browse-wrap enforcement, and have required more than mere website access to establish assent. Reddit’s theory will need to survive a motion to dismiss where Anthropic will likely argue that no reasonable bot operator would have constructive notice of buried terms.

The Trespass to Chattels Gambit

“Trespass to chattels” is the intentional, unauthorized interference with another’s tangible personal property (contrasted with real property) that impairs its condition, value, or use. Reddit asserts that Anthropic “trespassed” by scraping data from Reddit’s servers without permission.

Reddit’s trespass claim faces a high bar. California courts require proof of actual system impairment rather than mere unauthorized access. Reddit tries to meet this standard by citing CDN overage charges, server strain, and engineering time spent mitigating bot traffic. These bandwidth costs and engineering expenses, while real, may not rise to the level of system impairment that the courts demand.

The technical evidence will be crucial here. Reddit must demonstrate quantifiable performance degradation – slower response times, server crashes, or capacity limitations – rather than merely increased operational costs. This evidentiary burden may prove difficult given modern cloud infrastructure’s elastic scaling capabilities.

Unjust Enrichment and the Licensing Market

Reddit’s unjust enrichment claim rests on its data’s demonstrable market value, evidenced by licensing agreements with OpenAI, Google, and other AI companies. These deals, reportedly worth tens of millions annually, establish a market price for Reddit’s content.

The legal theory here is straightforward: Anthropic received the same valuable data as paying licensees but avoided the associated costs, creating an unfair competitive advantage. Under California law unjust enrichment requires showing that the defendant received a benefit that would be unjust to retain without compensation.

Reddit’s technically sophisticated Compliance API bolsters this claim. Licensed partners receive real-time deletion signals, content moderation flags, and structured data feeds that ensure training datasets remain current and compliant with user privacy preferences. Anthropic’s alleged automated data extraction bypassed these technical safeguards, potentially training on content that users had subsequently deleted or restricted.

Broader Implications for AI Governance

If Reddit’s contract theory succeeds, it would establish a powerful precedent allowing platforms to impose licensing requirements through terms of service. Every website with clear usage restrictions could potentially demand compensation from AI companies, fundamentally altering the economics of model training.

Conversely, if browse-wrap formation fails or federal preemption invalidates state law claims, AI developers would gain confidence that user generated web content remains accessible, subject to copyright limitations.

The Constitutional AI Paradox

Most damaging to Anthropic may be the reputational challenge to its “Constitutional AI” branding. The company has positioned itself as the ethical alternative in AI development, emphasizing safety and responsible practices. Reddit’s allegations create a narrative tension that extends beyond legal liability to market positioning.

This reputational dimension may drive settlement negotiations regardless of the legal merits, as Anthropic seeks to preserve its differentiated market position among enterprise customers increasingly focused on AI governance and compliance.

Conclusion

While Reddit’s legal claims face significant doctrinal challenges, the case underscores the importance of understanding both the technical architecture of web scraping and the evolving legal frameworks governing AI development. The outcome may determine whether platforms can use contractual mechanisms to assert control over their data assets, or whether AI companies can continue treating public web content as freely available training material subject only to copyright challenge.

by Lee Gesmer | May 27, 2025 | General

On May 9, 2025, the U.S. Copyright Office released what should have been the most significant copyright policy document of the year: Copyright and Artificial Intelligence – Part 3: Generative AI Training. This exhaustively researched report, the culmination of an August 2023 notice of inquiry that drew over 10,000 public comments, represents the Office’s most comprehensive analysis of how large-scale AI model training intersects with copyright law.

Crucially, the report takes a skeptical view of broad fair use claims for AI training, concluding that such use cannot be presumptively fair and must be evaluated case-by-case under traditional four-factor analysis. This position challenges the AI industry’s preferred narrative that training on copyrighted works is categorically protected speech, potentially exposing companies to significant liability for their current practices.

Instead of dominating the week’s intellectual property news, the report was immediately overshadowed by an unprecedented political upheaval that raises fundamental questions about agency independence and the rule of law.

Three Days in May

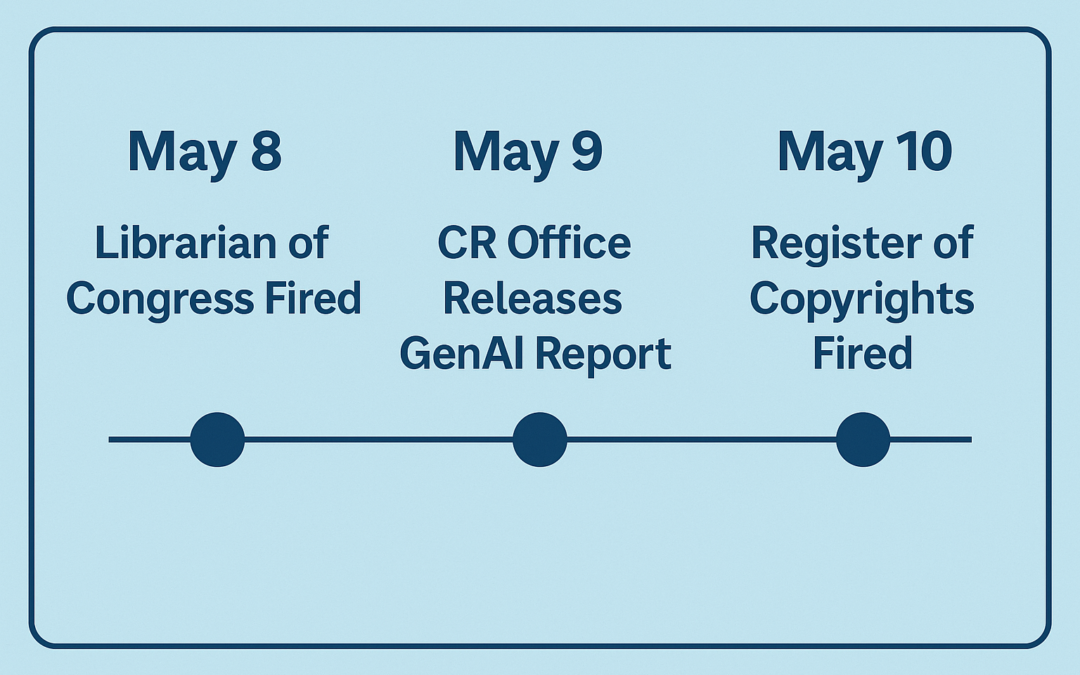

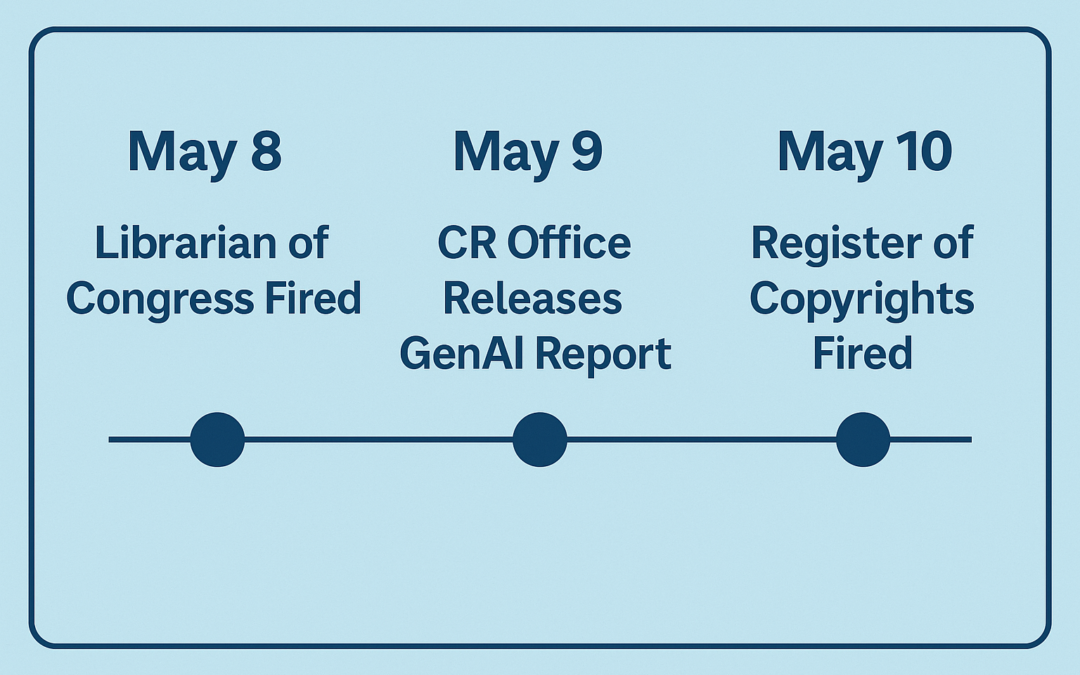

The sequence of events reads like a political thriller. On May 8—one day before the report’s release—Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden was summarily dismissed. Hayden held the sole statutory authority to hire and fire the Register of Copyrights. The report was issued on May 9, and the next day, May 10, Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter was fired by President Trump. Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche was appointed acting Librarian of Congress on May 12.

On May 22 Perlmutter filed suit against Blanche and Trump, alleging that her removal violated both statutory procedure and the Appointments Clause, and seeking judicial restoration to office.

The timing invites an obvious inference: the report’s conclusions displeased either the administration, powerful AI industry advocates, or both. As has been attributed to FDR, “In politics, nothing happens by accident. If it happens, you can bet it was planned that way.”

An Unprecedented “Pre-Publication” Label

The report itself carries a peculiar distinction. In the Copyright Office’s 128-year history of issuing over a hundred reports and studies, this marks the first time any policy document has been labeled a “pre-publication version.” A footnote explains that the Office released this draft “in response to congressional inquiries and expressions of interest from stakeholders,” promising a final version “without any substantive changes expected in the analysis or conclusions.”

any policy document has been labeled a “pre-publication version.” A footnote explains that the Office released this draft “in response to congressional inquiries and expressions of interest from stakeholders,” promising a final version “without any substantive changes expected in the analysis or conclusions.”

Whether Perlmutter rushed the draft online sensing her impending dismissal, or whether external pressure demanded early release, remains unexplained. What is clear is that this unusual designation complicates the document’s legal authority.

The Copyright Office as Policy Driver

Understanding the significance of these events requires recognizing that the Copyright Office is far more than a record-keeping/collection body. Congress expressly directs it to “conduct studies” and “advise Congress on national and international issues relating to copyright.” The Office serves as both a de facto think tank and policy driver in copyright law, with statutory responsibilities that make reports like this central to its mission.

The generative AI report exemplifies this role. It distills an enormous public record into a meticulous analysis of how AI training intersects with exclusive rights, market harm, and fair-use doctrine. The document is detailed, thoughtful, and comprehensive—representing the kind of scholarship you would expect from the nation’s premier copyright authority. Anyone seeking a balanced primer on generative AI and copyright should start here.

market harm, and fair-use doctrine. The document is detailed, thoughtful, and comprehensive—representing the kind of scholarship you would expect from the nation’s premier copyright authority. Anyone seeking a balanced primer on generative AI and copyright should start here.

Legal Weight in Limbo

While Copyright Office reports carry no binding legal precedent, federal courts often give them significant persuasive weight under Skidmore deference (Skidmore v. Swift, U.S. 1944), recognizing the Office’s particular expertise in copyright matters. The “pre-publication” designation, however, creates unprecedented complications.

Litigants will inevitably argue that a self-described draft lacks the settled authority of a finished report. If a final version emerges unchanged, that objection may evaporate. But if political pressure forces revisions or withdrawal, the May 9 report could become little more than a historical curiosity—a footnote documenting what the Copyright Office concluded before political intervention redirected its course.

The Chilling Effect

Even if the timing of the dismissals of the Librarian of Congress and Register of Copyrights on either side of the day the report was released was coincidental—a proposition that strains credulity—the optics alone threaten the Copyright Office’s independence. Future Registers will understand that publishing conclusions objectionable to influential constituencies, whether in the West Wing or Silicon Valley, can cost them their jobs.

This perception could chill precisely the kind of candid, expert analysis that Congress mandated the Office to provide. The sequence of events may discourage future agency forthrightness or embolden those seeking to influence administrative findings in politically fraught areas like AI regulation.

What Comes Next

For now, the “pre-publication” draft remains the Copyright Office’s most authoritative statement on generative AI training. Whether it survives intact, is quietly rewritten, or is abandoned altogether will reveal much about the agency’s future independence and the balance of power between copyright doctrine and the emerging AI economy.

The document currently exists in an unusual limbo—authoritative yet provisional. Its ultimate fate may signal whether copyright policy will be shaped by legal expertise and public input, or by political pressure and industry influence.

Until that question is resolved, the report stands as both a testament to rigorous policy analysis and a cautionary tale about the fragility of agency independence in an era of unprecedented technological and political change. The stakes extend far beyond copyright law—they touch on the fundamental question of whether expert agencies can fulfill their statutory duties free from political interference when their conclusions prove inconvenient to powerful interests.

The rule of law hangs in the balance, awaiting the next chapter in this extraordinary story.

by Lee Gesmer | May 14, 2025 | Copyright, DMCA/CDA, General

The Copyright Office has been engaged in a multi-year study of how copyright law intersects with artificial intelligence. That process culminated in a series of three separate reports: Part 1 – Unauthorized Digital Replicas, Part 2 – Copyrightability, and now, the much-anticipated Part 3—Generative AI Training.

Many in the copyright community anticipated that the arrival of Part 3 would be the most important and controversial. It addresses a central legal question in the flood of recent litigation against AI companies: whether using copyrighted works as training data for generative AI qualifies as fair use. While the views of the Copyright Office are not binding on courts, they often carry persuasive weight with federal judges and legislators.

The Report Arrives, Along With Political Controversy

The Copyright Office finally issued its report – Copyright and Artificial Intelligence – Part 3 Generative AI Training (link on Copyright Office website; back-up link here) on Friday, May 9, 2025. But this was no routine publication. The document came with an unusual designation: “Pre-Publication Version.”

Then came the shock. The following day, Shira Perlmutter, the Register of Copyrights and nominal author of the report, was fired. Perlmutter had served in the role since October 2020, appointed by Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden—herself fired two days earlier, on May 8, 2025.

These abrupt, unexplained dismissals have rocked the copyright community. The timing has fueled speculation of political interference linked to concerns from the tech sector. Much of the conjecture has centered on Elon Musk and xAI, his artificial intelligence company, which may face copyright claims over the training of its Grok LLM model.

Adding to the mystery is the “pre-publication” label itself—something the Copyright Office has not used before. The appearance of this label, followed by Perlmutter’s termination, has prompted widespread belief that the report’s contents were viewed as too unfriendly to the AI industry’s legal position, and that her removal was a prelude to a potential retraction or revision.

What’s In That Report, Anyway?

Why might this report have rattled so many cages?

In short, it delivers a sharp rebuke to the AI industry’s prevailing fair use narrative. While the Office does not conclude that AI training is categorically infringing, its analytical framework casts deep doubt on the broad legality of using copyrighted works without permission to train generative models.

Here are key takeaways:

Transformative use? At the heart of the report is a skeptical view of whether using copyrighted works to train an AI model is “transformative” under Supreme Court precedent. The Office states that such use typically does not “comment on, criticize, or otherwise engage with” the copyrighted works in a way that transforms their meaning or message. Instead, it describes training as a “non-expressive” use that merely “extracts information about linguistic or aesthetic patterns” from copyrighted works—a use that courts may find insufficiently transformative.

Commercial use? The report flatly rejects the argument that AI training should be considered “non-commercial” simply because the outputs are new or the process is computational. Training large models is a commercial enterprise by for-profit companies seeking to monetize the results, and that, the Office emphasizes, weighs against fair use under the first factor.

Amount and substantiality? Many AI models are trained on entire books, images, or articles. The Office notes that this factor weighs against fair use when the entirety of a work is copied—even if only to extract patterns—particularly when that use is not clearly transformative.

Market harm? Here, the Office sounds the loudest alarm. It directly links unauthorized AI training to lost licensing opportunities, emerging collective licensing schemes, and potential market harm. The Office also notes that AI companies have begun entering into licensing deals with rightsholders—ironically undercutting their own arguments that licensing is impractical. As the Office puts it, the emergence of such markets suggests that fair use should not apply, because a functioning market for licenses is precisely what the fourth factor is meant to protect.

But Google Books? The report goes out of its way to distinguish training on entire works from cases like Authors Guild v. Google, where digitized snippets were used for a non-expressive, publicly beneficial purpose—search. AI training, by contrast, is described as for-profit, opaque, and producing outputs that may compete with the original works themselves.

Collectively, these conclusions paint a picture of AI training as a weak candidate for fair use protection. The report doesn’t resolve the issue, but it offers courts a comprehensive framework for rejecting broad fair use claims. And it sends a strong signal to Congress that licensing—statutory or voluntary—may be the appropriate policy response.

Conclusion

It didn’t take long for litigants to seize on the report. The plaintiffs in Kadrey v. Meta (which I recently wrote about here) filed a Statement of Supplemental Authority on May 12, 2025, the very next business day, citing Ninth Circuit authority that Copyright Office reports may be persuasive in arriving at judicial decisions (but failing to note that the report in question here is “pre-publication”). The report was submitted to judges in other active AI copyright cases as well.

The coming weeks may determine whether this report is a high-water mark in the Copyright Office’s independence or the opening move in its politicization. The “pre-publication” status may lead to a walk-back under new leadership. If, on the other hand, the report is published as final without substantive change, it may become a touchstone in the pending cases and influence future legislation.

If it survives, the legal debate over generative AI may have moved into a new phase—one where assertions of fair use must confront a detailed, skeptical, and institutionally backed counterargument.

As for the firing of Shira Perlmutter and Carla Hayden? No official explanation has been offered. But when the nation’s top copyright official is fired within 24 hours of issuing what could prove to be the most consequential copyright report in a generation, the message—intentional or not—is that politics may be catching up to policy.

Copyright and Artificial Intelligence, Part 3: Generative AI Training (pre-publication)

by Lee Gesmer | Apr 28, 2025 | Copyright

“Move fast and break things.” Mark Zuckerberg’s famous motto seems especially apt when examining how Meta developed Llama, its flagship AI model.

Like OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, and others, Meta faces copyright lawsuits for using massive amounts of copyrighted material to train its large language models (LLMs). However, the claims against Meta go further. In Kadrey v. Meta, the plaintiffs allege that Meta didn’t just scrape data — it pirated it, using BitTorrent to pull hundreds of terabytes of copyrighted books from shadow libraries like LibGen and Z-Library.

This decision could significantly weaken Meta’s fair use defense and reshape the legal framework for AI training-data acquisition.

Meta’s BitTorrent Activities

In Kadrey v. Meta, plaintiffs allege that discovery has revealed that Meta’s GenAI team pivoted from tentative licensing discussions with publishers to mass BitTorrent downloading after receiving internal approvals that allegedly escalated “all the way to MZ”—Mark Zuckerberg.

BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer file-sharing protocol that efficiently distributes large files by breaking them into small pieces and sharing them across a decentralized “swarm” of users. Once a user downloads a piece, they immediately begin uploading it to others—a process known as “seeding.” While BitTorrent powers many legitimate projects like open source software distribution, it’s also the lifeblood of piracy networks. Courts have long treated unauthorized BitTorrent traffic as textbook copyright infringement (e.g., Glacier Films v. Turchin, 9th Cir. 2018).

The plaintiffs allege that Meta engineers, worried that BitTorrent “doesn’t feel right for a Fortune 500 company,” nevertheless torrented 267 terabytes between April and June 2024—roughly twenty Libraries of Congress worth of data. This included the entire LibGen non-fiction archive, Z-Library’s cache, and massive swaths of the Internet Archive. According to the plaintiffs’ forensic analysis, Meta’s servers re-seeded the files back into the swarm, effectively redistributing mountains of pirated works.

The Legal Framework and Why BitTorrent Matters

Meta’s alleged use of BitTorrent complicates its copyright defense in several critical ways:

1. Reproduction vs. Distribution Liability

Most LLM training involves reproducing copyrighted works, which defendants typically argue is protected as fair use. But BitTorrent introduces unauthorized distribution under § 106(3) of the Copyright Act. Even if the court finds Llama’s training to be fair use, unauthorized seeding could constitute a separate violation harder to defend as transformative.

2. Willfulness and Statutory Damages

Internal communications allegedly showed engineers warning about the legal risks, describing the pirated sources as “dodgy,” and joking about torrenting from corporate laptops. Plaintiffs allege that Meta ran the jobs on Amazon Web Services rather than Facebook servers, in a deliberate effort to make the traffic harder to trace back to Menlo Park. If proven, these facts could support a finding of willful infringement, exposing Meta to enhanced statutory damages of up to $150,000 per infringed work.

3. “Unclean Hands” and Fair Use Implications

The method of acquisition may significantly impact fair use analysis. Plaintiffs point to Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprise (1985), where the Supreme Court found that bad faith acquisition—stealing Gerald Ford’s manuscript—undermined the defendant’s fair use defense. They argue that torrenting from pirate libraries is today’s equivalent of exploiting a purloined manuscript.

Meta’s Defense and Its Vulnerabilities

Meta argues that its use of the plaintiffs’ books is transformative: it extracts statistical patterns, not expressive content. They rely on Authors Guild v. Google Books (2nd Cir. 2015) and emphasize that fair use focuses on how a work is used, not obtained. Meta claims that its engineers took steps to minimize seeding—however, the internal data logs that would prove this are missing.

The company also frames Llama’s outputs as new, non-infringing content—asserting that bad faith, even if proven, should not defeat fair use.

However, the plaintiffs counter that Llama differs from Google Books in key respects:

– Substitution risk: Llama is a commercial product capable of producing long passages that may mimic authors’ voices, not merely displaying snippets.

– Scale: The amount of copying—terabytes of entire book databases—dwarfs that upheld in Google Books.

– Market harm: Licensing markets for AI training datasets are emerging, and Meta’s decision to torrent pirated copies directly undermines that market.

Moreover, courts have routinely rejected defenses based on the idea that pirated material is “publicly available.” Downloading infringing content over BitTorrent has never been viewed kindly—even when defendants claimed to have good intentions.

Even if Meta persuades the court that its training of Llama is transformative, the torrenting evidence remains a serious threat because:

– The automatic seeding function of BitTorrent means Meta likely distributed copyrighted material, independent of any transformative use

– The apparent bad faith (jokes about piracy, euphemisms describing pirated archives as “public” datasets) and efforts to conceal traffic present a damaging narrative

– The deletion of torrent logs may support an adverse inference that distribution occurred

– Judge Vince Chhabria might prefer to decide the case on familiar grounds—traditional copyright infringement—rather than attempting to set sweeping precedent on AI fair use

Broader Implications

If the court rules that unlawful acquisition via BitTorrent taints subsequent transformative uses, the AI industry will face a paradigm shift. Companies will need to document clean sourcing for training datasets—or face massive statutory damages.

If Meta prevails, however, it may open the door for more aggressive data acquisition practices: anything “publicly available” online could become fair game for AI training, so long as the final product is sufficiently transformative.

Regardless of the outcome, the record in Kadrey v. Meta is already reshaping AI companies’ risk calculus. “Scrape now, pay later” is beginning to look less like a clever strategy and more like a legal time bomb.

Conclusion

BitTorrent itself isn’t on trial in Kadrey v. Meta, but its DNA lies at the center of the dispute. For decades, most fair use battles have focused on how a copyrighted work is exploited. This case asks a new threshold question: does how you got the work come first?

The answer could define how the next generation of AI is built.