by Lee Gesmer | Jun 27, 2014 | Copyright

In the end Aereo’s dime-sized antennas and subscriber-specific copies of television broadcasts – its “Rube Goldberg” attempt to find a loophole that would allow it to stream TV over the Internet – were not enough to win over a majority of the Supreme Court.

On June 25, 2014, the Supreme Court held that Aereo’s streaming service violated the exclusive right of copyright owners to “publicly perform” their works. Aereo had used diabolically clever technology (or so the broadcasters claimed) in its attempt to avoid this outcome, which seems very likely to force Aereo out of business.

As I have described in detail elsewhere, Aereo’s system – which would have been unimaginable and cost-prohibitive only a few years ago – relied on thousands of antennas and massive, low-cost hard disk storage. Advances in antenna technology allowed Aereo to assign a separate micro-antenna to each paid subscriber. The plummeting cost of digital storage allowed Aereo to save a separate copy of each broadcast transmission for each subscriber that wanted to save a copy.

Aereo’s argument was that for any singe subscriber this was no different (legally speaking) than accessing a broadcast using a rooftop TV antenna connected to a DVR in the living room. In effect, Aereo claimed, each subscriber had outsourced the antenna and the remote DVR to Aereo’s central facility, and Aereo was no more than an equipment supplier.

And, Aereo argued, nothing was accessed or copied unless the consumer initiated access and decided to watch or save a show. In other words, Aereo didn’t collect TV shows and provide a ready-to-access “TV jukebox” the consumer could choose shows from, à la Netflix. If none of Aereo’s subscribers initiated a copy of the “Barney and Friends,” broadcast at 3:00 a.m. on WNET in New York (one of the plaintiffs in the case), it would never be accessed, saved or streamed by Aereo. It was the “volitional conduct” (an esoteric copyright law buzz-phrase) of the subscriber that caused a copy to be made and transmitted, just as it is the volitional conduct of a library patron that causes a photocopy of a copyrighted work to be made on a library photocopier. Aereo argued that it should be no more liable for what its subscribers do with the equipment than is a library with a copy machine on its premises (libraries are not legally responsible for illegal copying by their patrons).

Further, Aereo argued, the fact that it may have transmitted 10,000 personal copies of a World Cup soccer match didn’t constitute a public performance under the Copyright Act, since each transmission was viewed by only one subscriber, not the “public.”

These arguments were enough to persuade the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York (a court many lawyers view as the most knowledgeable and influential of the federal courts when it comes to copyright law), but it didn’t pass muster with the Supreme Court (although three justices dissented, agreeing with Aereo). The Court was unimpressed with the technological details that had occupied the lower courts that had ruled in favor of Aereo, observing that it “did not see how the fact that Aereo transmits via personal copies of programs” makes a difference under the copyright statute. Likewise, the Court rejected Aereo’s argument that transmitting a performance means to make a single transmission, holding that Aereo was transmitting a performance through a “multiple, discrete transmissions.”

Drawing heavily on Congress’ 1976 amendment to the copyright statute intended to bring cable TV companies within the definition of “public performance,” the Supreme Court concluded by analogy that Aereo’s “is not simply an equipment provider . . . that Aereo’s activities are substantially similar to those of the CATV companies that Congress amended the Act to reach.” And, because the fit between the 1976 law and Aereo’s technology was so imperfect, the Court was forced to fall back on what it described as the “overwhelming likeness to the cable companies targeted by the 1976 amendments” and conclude that the technological differences between Aereo and the cable companies “does not make a critical difference.”

Fundamentally, the Court focused on Congress’ regulatory objectives, and on this basis considered Aereo’s technological system of dedicated antennas and personal copies as “not adequate to place Aereo’s activities outside the scope of the Act,” a conclusion the dissent described as a “looks-like-cable-TV” (or“ guilt by resemblance”) standard that will “sow confusion for years to come” and is “nothing but th’ ol’ totality-of-the-circumstances test (which is not a test at all but merely assertion of an intent to perform test-free, ad hoc, case-by-case evaluation).”

* * *

There is no question that had Aereo won before the Supreme Court it would have been a huge upset, and the fourth estate would be doing somersaults. As it is, the outcome was largely anticipated by the small group of lawyers, academics and commentators that paid close attention to the legal arguments made by each side. While most of us prefer to see David defeat Goliath, it has always seemed unlikely that the networks’ $3 billion-plus annual licensing revenues would be weakened by Aereo or Aereo clones.

However, questions remain over what the Court’s ruling (and reasoning) will mean for the delivery of television programming, cloud computing or service-provider liability. Is the dissent correct when it warns that it “will take years, perhaps decades, to determine which automated systems now in existence are governed by the traditional volitional-conduct test and which get the Aereo treatment. (And automated systems now in contemplation will have to take their chances)”?

The answer to these questions is, of course, that it’s far too early to tell. For better or worse, the Supreme Court was careful to emphasize that its decision was limited to the “technologically complex” system engineered by Aereo: “we cannot now answer more precisely how the Transmit Clause or other provisions of the Copyright Act will apply to technologies not before us.” Even so, the Court was careful to note that its decision didn’t reach remote storage (“cloud locker”) services where consumers are able to store digital copies they “have already lawfully acquired.”

Nevertheless, start-ups involved in the delivery of television programming will have to ask whether they cross the line set by Aereo: are they merely an equipment provider (and not liable for direct infringement) or a cable TV look-alike that falls on the wrong side of the line between legality and illegality?

The Supreme Court did little to help companies answer this question, and there may be real concern that Aereo will discourage investment in alternatives to traditional television programming. One thing that seems certain is that any almost every investor in a television technology company will have to ask whether the business plan passes the “Aereo test,” i.e., is copyright compliant. Remote service DVR (“RS-DVR”) services, in particular, may need to reexamine the legality of their services following this decision. Commentators have already questioned whether Aereo has implications for the legality of in-line streaming and in-line linking of images, and noted that regardless of whether the answer is yes or no, the case is likely to raise litigation costs, and thus indirectly chill innovation.

With respect to non-broadcast TV content — for example, the “cloud computing industry” and “cloud lockers” that were the subject of concern expressed by some Justices during oral argument before the Court — it seems unlikely that there will be any implications, at least in the short term, for the reasons described in my post titled Aereo and the Cloud Before the Supreme Court, written just before the Supreme Court decision was issued. Most cloud services provide access to content they own or license, or store files that consumers have already lawfully acquired, a practice the Supreme Court noted was not impacted by its decision. And, cloud services that host third-party content are largely protected (although not entirely) by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

However, copyright law inevitably lags technological development, creating a seemingly never-ending state of uncertainty over how the law will be applied to new technologies. Indeed, Aereo itself illustrates this – the Supreme Court was called on to apply a statute enacted in 1976 to a technology that could not have been envisioned by Congress until decades later. What unintended consequences Aereo might have for innovation and investment in content-delivery and content-storage technologies yet to be invented or imagined is anyone’s guess.

American Broadcasting v. Aereo, Inc. (June 25, 2014)

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 21, 2014 | Copyright

This is a catch-up post on oral argument in ABC v. Aereo, which was held on April 22, 2014.

The Supreme Court’s 2013-2014 term is almost over, and we can expect to receive the Court’s decision in Aereo on June 23rd or 30th.

A great deal has been written about whether Aereo’s TV -to-Internet service violates the TV networks’ public performance right under the transmit clause of the Copyright Act. By comparison, less has been written about the implications of the case for “cloud computing” and “cloud lockers.”*

*note: the “cloud” is simply a metaphor for data and computing power accessed via the Internet.

When the Aereo case was argued before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in November 2012 the “cloud” was not mentioned once. (transcript) However, by the time the case reached oral argument before the Supreme Court in April 2014 cloud computing — or the implications of a Supreme Court decision in Aereo on cloud computing — seemed to have become the focus of the case. Amicus briefs supporting Aereo predicted dire consequence for cloud computing if the Court ruled in favor of the networks,* and the “cloud” is mentioned more than 30 times in the argument transcript,

*note: For example, one amicus brief supporting Aereo warned of “unintended consequences” and argued that the tests proposed by the networks, their amici and the United States “are unworkable and will endanger the thriving cloud computing industry just as it starts to mature.” (link)

What was the Court’s concern about cloud computing, and how did the attorneys for the parties handle the issue?

While the Supreme Court judges didn’t identify their specific concerns about how a decision for the networks might impact cloud computing, they repeatedly referenced it. For example, at the very outset of oral argument Justice Breyer was so concerned about this issue that he questioned whether it would be easier to remand the case to determine whether Aereo is a cable company subject to a compulsory license in order to avoid addressing “serious problems . . . like the cloud.”

The networks’ attorney urged the Court “not to decide the cloud computing question once and for all today, because not all cloud computing is created equal.” (An argument at least one Justice found unsatisfying). Aereo’s lawyer capitalized on this line of questioning, beginning his argument with the assertion that the networks’ interpretation of the copyright statute “absolutely threatens cloud computing.” He argued that the cloud computing industry was “freaked out about this case” because it had invested “tens of billions of dollars” in reliance on the legal principles Aereo was defending.

The attorney for the United States (which sided with the networks) made the best attempt to respond to the justices’ concerns, explaining that “if you have a cloud locker service, somebody has bought a digital copy of a song or a movie from some other source, stores it in a locker and asks that it be streamed back, the cloud locker and storage service is not providing the content. It’s providing a mechanism for watching it.” In other words, a cloud locker service that provides a user access to copies of copyrighted content that the user already has legally obtained would not violate the public performance right.

The Justices, for their part, did more to confuse matters than they did to clarify the issue. Justice Kagan described a system in which “companies where many, many thousands or millions of people put things up there, and then they share them, and the company in some ways aggregates and sorts all that content” and asked the networks’ attorney how a decision against Aereo would impact such a (presumably illegal) Megaupload-like service. Justice Sotomayor confused matters with her reference to the non-existent “iDrop in the cloud” and her apparent lack of awareness that Roku is not a content provider, but a piece of hardware that allows subscribes to access programming services such as Netflix. Justice Scalia asked a question that suggested he might think HBO (a cable channel) was delivered free over the airwaves, and therefore would be susceptible to re-broadcast by Aereo.

Setting aside the melange of law, fact and misinformation at oral argument of the Aereo case the question remains: what would a ruling against Aereo mean for cloud lockers or the “cloud industry”?

The answer, it appears, is very little, since the key question in any cloud storage/copyright case is likely to be, “who provides the content that resides in the cloud locker”?

There are several possible scenarios: First, most data in the “cloud” is either created or licensed by the provider. Subscribers to the New York Times, Wired Magazine and Netflix stream or download files from the cloud. In each of these and thousands of similar services, the content is owned or licensed by the site, and access is restricted to paying subscribers. A Supreme Court ruling against Aereo will have no impact on this part of the “cloud industry.” A variant on this model is where the user already possesses a copy of a file, and “scan-and-match”* technology allows the user to access files on a centralized database maintained in the cloud. Popular “music lockers” provided by Google, Apple and Amazon are good examples of this hybrid model. Again, a decision against Aereo will not affect this model of cloud computing.

*note: Using “scan-and-match” technologies the cloud service maintains one licensed copy of each song, and “matches” the subscriber’s collection against each song in the database. This avoids requiring the user to upload her library to the service (an often time-consuming process) and eliminates the requirement that the service maintain a copy of each file the user uploads, greatly reducing storage requirements.

Second, where content is uploaded to the cloud by a user or subscriber in the first instance and is universally accessible, the cloud service is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s (DMCA) notice and take down provisions.* A popular example of this type of cloud service is YouTube. This model would not be adversely impacted by a decision against Aereo.

note: Although Aereo mentioned the DMCA in passing in its brief to the Supreme Court, it has never argued that it is entitled to immunity under the DMCA safe harbors, seemingly conceding that Aereo is the content provider of the TV shows at issue, not Aereo’s users.

Third, in cases where users upload files that are stored individually (e.g., 10,000 copies of “Stairway to Heaven” uploaded and stored separately), the storage site allows only the person who uploaded the file to access it (so-called user-specific transmissions), avoiding copyright liability under the public performance provision based on a combination of fair use (“space shifting” by the user) and application of the “volitional conduct doctrine” by the cloud service.*

*note: Under the “volitional conduct doctrine” a technology provider is not liable for direct copyright infringement when it provides the means for infringement but that infringement is controlled by the “volitional conduct” of the users. An example would be a copy shop. The difficult question, under this line of cases, is whether the technology provider is sufficiently actively engaged in the process to be liable.

Aereo — which copies over-the-air TV transmissions directly and supplies copyrighted content to its subscribers — fits within none of these models, leaving the Supreme Court plenty of room to conclude that Aereo’s argument that a ruling against it will signal a death knell for cloud computing technologies is little more than a straw man argument. The Court can rule against Aereo while making clear that it has no intent to interfer with cloud-based services that use licensed content or provide storage for content the end-user independently possesses and elects to store in the cloud.

My prediction: the Supreme Court will do exactly that, leaving any “close cases” that may arise in the future for the lower courts to resolve.

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 16, 2014 | Copyright

I am proud to have been a member of the CopyrightX class of 2014. If you have any doubts about the merits of online education, apply to take this course in 2015. You will be pleasantly surprised at how effective this form of education can be.

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 13, 2014 | Copyright

While The Author’s Guild copyright suit against Google Books has received most of the attention on the copyright law front, its smaller sibling – the Author’s copyright suit against HathiTrust – has been proceeding on a parallel track. HathiTrust is a consortium of more than 70 institutions working with Google to digitize the books in their libraries, but a smaller number of books than Google Books (only ten million), and for academic use (including an accommodation for disabled viewers), compared with Google Books’s commercial use.

On June 10, 2014, the Second Circuit upheld the federal district court, holding that HathiTrust is protected from copyright infringement under the fair use doctrine. With respect to full-text search (the most legally problematic aspect of HathiTrust), the Second Circuit held:

- “[T]he creation of a full‐text searchable database is a quintessentially transformative use” because it serves a “new and different function.”

- The nature of the copyrighted work (the second factor under fair use analysis) is “of limited usefulness where as here, ‘ the creative work … is being used for a transformative purpose.’”

- The copying was not excessive since “it was reasonably necessary for [HathiTrust] to make use of the entirety of the works in order to enable the full‐text search function.”

- And lastly, “full‐text‐search use poses no harm to any existing or potential traditional market” since full-text search “does not serve as a substitute for the books that are being searched.”

Citing HathiTrust’s “extensive security measures,” the court rejected as speculative the Author’s argument that “existence of the digital copies creates the risk of a security breach which might impose irreparable damage on the Authors and their works.”*

*note: In an earlier post I discussed the Guild’s argument that Google Books creates the ”all too real risks of hacking, theft and widespread distribution.” As I noted in that post, in describing that risk the Guild leaves nothing to the imagination: “just one security breach could result in devastating losses to the rightholders of the books Google has subjected to the risk of such a breach by digitizing them and placing them on the Internet.” In response to similar arguments in HathiTrust the Second Circuit found that there is “no basis in the record on which to conclude that a security breach is likely to occur.”

HathiTrust is distinguishable from Google Books in one significant respect. Non-disabled users can search the HathiTrust database for content, but unlike Google Books, which displays “snippets” of copyrighted works, unless the copyright holder authorizes broader use the results only show page numbers where search terms appear in a given work.

HathiTrust offers additional features to users with disabilities, who can access complete copies if they can show that they are unable to read a work in print. However, the Second Circuit made short shrift of this issue, holding that “the doctrine of fair use allows the Libraries to provide full digital access to copyrighted works to their print-disabled patrons.”

Even taking into consideration the fact that the non-disabled-access HathiTrust library can be distinguished from Google Books on the grounds that it does not provide “snippets,” it is difficult to see how the outcome will be different in the Guild’s appeal of Google Books. The Second Circuit’s central rationales in support of fair use in HathiTrust — that full-text search is transformative and that the database does not serve as a substitute for the books being searched (the latter factor being true in snippet-enabled Google Books as well as in HathiTrust) — likely foretell the fate of the Google Books case* (link), where the federal district court ruled in favor of Google on similar grounds. (For a full discussion of district court decision in the Google Books litigation, click here).

*note: The Author’s Guild suit targeting Google Books is on appeal to the Second Circuit.

Author’s Guild v. Hathitrust, 755 F.3d 87 (2nd Cir. 2014)

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 11, 2014 | Copyright

The idea behind statutes of limitations is usually straightforward. If someone commits an illegal act, after a certain period of time they can no longer be liable (or prosecuted) for that act. In civil cases the statute of limitations usually begins to run when the injured party knew or should have known of the illegal act. Once that period has passed, the injured party is barred from filing a lawsuit. For example, in Massachusetts the statute of limitations for most tort actions is three years. If you are the victim of a tort (for example, medical malpractice), you must file suit within three years of the act that caused you harm, or you likely are barred by the statute of limitations.*

*note: Like almost everything in the law, there are exceptions and nuances to this.

The U.S. Copyright Act contains a three year statute of limitations (17 U.S.C. Section 507),* but the way in which the statute is applied is different. A copyright holder may know that a defendant has been selling an infringing product for more than three years, but that doesn’t bar an action for copyright infringement – the defendant may still be liable for any infringing conduct taken during the three year period before the suit was filed. This is described as a “three-year look back,” a “rolling limitations period” or the “separate-accrual rule.”**

*note: The statute provides that “No civil action shall be maintained under the provisions of this title unless it is commenced within three years after the claim accrued.”

**note: A new statute of limitations “accrues” (commences) with each new infringement.

In theory, therefore, a copyright owner can become aware of an infringing use of her work and do nothing for an indefinite period of time – more than just three years – until, for example, she concludes that the infringer has earned profits that could be recovered as damages and therefore justify the cost of a lawsuit. At that point the copyright owner can file suit and the statute of limitations will come into play, but only to limit damages to the preceding three year period. However, if the copyright owner wins her case and the defendant doesn’t settle there is the possibility that the copyright owner will wait three years and then file another infringement suit based on infringing actions taken during the second three year period. And so on, ad infinitum (or so it will seem to the defendant, given the length of copyright protection).

Until recently infringers were not wholly at the mercy of this strategy. They were able to raise the common law legal doctrine of “laches,” a doctrine which may bar a lawsuit based on an unreasonable, prejudicial delay in commencing suit. In many cases defendants successfully arged that a copyright owner should not be permitted to wait beyond three years before filing an infringement suit.

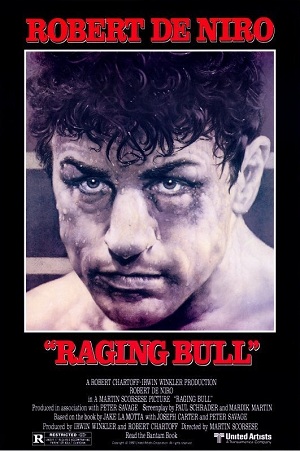

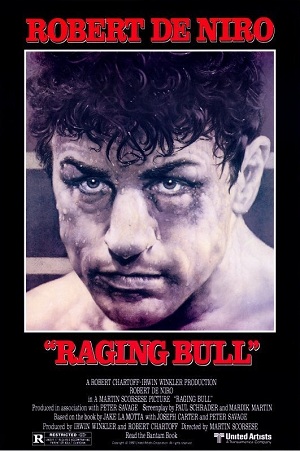

These two legal principles — the three-year copyright statute of limitations and the laches doctrine — came into collision when Paulla Petrella brought a copyright suit against MGM. Since 1981 Petrella has been the heir to her  father Frank Petrella’s copyright interest in a book and two screenplays about the life of Jake LaMotta, the central character portrayed in the film Raging Bull. She asserts that Raging Bull is a derivative work of the book and screenplays, and that she is entitled to royalties based on MGM’s distribution of the film during the three years preceding her suit.

father Frank Petrella’s copyright interest in a book and two screenplays about the life of Jake LaMotta, the central character portrayed in the film Raging Bull. She asserts that Raging Bull is a derivative work of the book and screenplays, and that she is entitled to royalties based on MGM’s distribution of the film during the three years preceding her suit.

Ms. Petrella had threatened MGM with a suit for copyright infringement as far back as 1998, but she didn’t actually file suit until 2009. In fact, Raging Bull was released in 1980, and there is evidence that Ms. Petrella was aware of her copyright infringement claim as far back as 1981, in which case she delayed for almost 30 years before filing suit for copyright infringement.

MGM raised the defense of laches, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, dismissing the suit. The Supreme Court took the case and reversed in a 6-3 decision, holding that, except in “extraordinary circumstances,” laches cannot be invoked to preclude a claim for damages that falls within the three-year window. However, this was not a clear win for Petrella or others in her position: oddly, the Court held that delay is relevant to equitable relief which (the Court stated), includes not only an injunction against further public display or distribution of the copyrighted work, but also damages based on the infringer’s profits that are attributable to the infringement.

Whether this decision leads to a flood of hitherto dormant copyright suits remains to be seen, and may be influenced by how the lower  courts interpret and apply the decision. For example, given the Supreme Court’s comments it is uncertain that Ms. Petrella will be able to obtain an injunction against future sales of Raging Bull, and the Court’s statement that a delay in bringing suit is relevant to determining damages based on MGM’s profits during the three year period may limit any recovery by allowing MGM to use its investment in the film prior to the three-year look-back period to offset profits earned during those three years. Therefore, the extent of any potential monetary recovery is unclear.

courts interpret and apply the decision. For example, given the Supreme Court’s comments it is uncertain that Ms. Petrella will be able to obtain an injunction against future sales of Raging Bull, and the Court’s statement that a delay in bringing suit is relevant to determining damages based on MGM’s profits during the three year period may limit any recovery by allowing MGM to use its investment in the film prior to the three-year look-back period to offset profits earned during those three years. Therefore, the extent of any potential monetary recovery is unclear.

*note: Although, as discussed above, assuming Petrella establishes liability (an issue yet to be addressed in this case) and MGM continues to distribute the film, in theory Petrella could file a series of lawsuits every three years seeking MGM’s profits for the preceding three year period. After the first suit MGM would be on notice that it is exploiting a copyright-protected work, and would likely have little choice but to to settle the case, rather than have this sword of Damocles hanging over its head.

Many observers in the copyright community think that Petrella may lead to a wave of lawsuits by copyright holders who had assumed, until now, that their claims might be barred by laches. A prominent example suggesting this may be the case is the May 31, 2014 lawsuit filed by the Randy Craig Wolfe Trust against the members of Led Zeppelin. Wolfe, the deceased founder and creative force behind the band Spirit, had believed since the mid-’90s (and perhaps as far back as 1971) that the intro to Stairway to Heaven had been copied from Taurus, a song on a Spirit album released in 1968. It seems unlikely that this case, filed less than two weeks after the Petrella decision, was not encouraged by the outcome in Petrella.

Petrella could also have implications for application of the laches doctrine under patent law. As the Supreme Court noted in Petrella, the Federal Circuit has held that laches may be used to bar patent damages prior to the actual commencement of suit. The courts may conclude that the rationale of the Supreme Court in Petrella applies under the patent statute as well, making it easier for patent plaintiffs to take advantage of the full six year statute of limitations under the patent statute.

Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., No. 12-1315 (May 19, 2014)

Scotusblog page on Petrella

by Lee Gesmer | May 10, 2014 | Copyright

On November 26, 2013 I wrote a post titled “Oracle v. Google: How Google Could Lose on Appeal” (link). After oral argument before the CAFC a couple of weeks later I wrote a follow-up post, “Oral Argument in Oracle v. Google: A Setback for Google?” (link).

I thought I was being a bit paranoid on Google’s behalf, but I was wrong – if anything, I was being too optimistic. The CAFC reversed California federal district court judge William Alsup, upholding almost every argument made by Oracle.

Interoperatibility Goes To Fair Use, Not Copyrightability

In the “How Google Could Lose” post I noted that Oracle had a good argument that interoperability is properly raised in connection with a copyright fair use defense, not to determine whether the plaintiff’s work is copyright-protected in the first instance. The CAFC agreed, stating

Whether Google’s software is “interoperable” in some sense with any aspect of the Java platform … has no bearing on the threshold question of whether Oracle’s software is copyrightable. It is the interoperability and other needs of Oracle—not those of Google—that apply in the copyrightability context, and there is no evidence that when Oracle created the Java API packages at issue it did so to meet compatibility requirements of other pre-existing programs.

Filtration for Interoperatility Should be Performed Ex Ante, Not Ex Post

In “How Google Could Lose” I noted that:

under Altai it is the first programmer’s work (in this case Oracle) that is filtered, not the alleged infringer’s work (in this case Google), and the filtration is performed as of the time the first work is created (ex ante) not as of the date of infringement (ex post). When Oracle created the Java API it did not do so to meet compatibility requirements of other programs. Thus, copyright protection of the Java API was not invalidated by compatibility requirements at the time it was created.

The CAFC agreed, stating:

[W]e conclude that the district court erred in focusing its interoperability analysis on Google’s desires for its Android software … It is the interoperability and other needs of Oracle—not those of Google—that apply in the copyrightability context, and there is no evidence that when Oracle created the Java API packages at issue it did so to meet compatibility requirements of other pre-existing programs.

Lotus v. Borland Is Not the Law in the Ninth Circuit

In the “How Google Could Lose” post I noted that

“a close reading of Judge Alsup’s decision in Oracle/Google could lead one to conclude that this was the sole basis on which Judge Alsup found the structure of the Java API declaring code to be uncopyrightable, and therefore affirmance or reversal may depend on whether the CAFC concludes that Judge Alsup properly applied Lotus in Oracle/Google. . . . The CAFC could even reject Lotus outright, and hold that a system of commands is not a “method of operation” under §102(b). Both the Third and Tenth Circuits have indicated that the fact that the words of a program are used in the implementation of a process should not affect their copyrightability, and the CAFC could conclude that this is the appropriate approach under Ninth Circuit law.

In fact, this is exactly what the CAFC concluded:

[T]he Ninth Circuit has not adopted the [First Circuit’s] “method of operation” reasoning in Lotus, and we conclude that it is inconsistent with binding precedent. Specifically, we find that Lotus is incompatible with Ninth Circuit case law recognizing that the structure, sequence, and organization of a computer program is eligible for copyright protection where it qualifies as an expression of an idea, rather than the idea itself.

The only consolation that Google can take from this decision is that the court rejected Oracle’s argument that Google’s adoption of the Java declaring code did not qualify for fair use. Instead, the CAFC sent the case back to the federal district court for reconsideration (summary judgment motions and perhaps a trial) on that issue. Or, actually, a retrial, since the first jury trial on fair use resulted in a hung jury. However, as I read the decision, it seems to favor Oracle’s position on fair use, and I predict that Google will be hard pressed to justify its copying of the Java API declaring code based on fair use.

Perhaps the case will settle now, but Larry Ellison is not one to back down when he has the advantage. I suspect there are intellectual property damages experts across America dreaming of the case of a lifetime this weekend.

I gave an extensive presentation on Oracle v. Google at the Boston Bar Association on November 13, 2013. To see the slides, click here.

Oracle America, Inc. v. Google, Inc. (CAFC, May 9, 2014)

by Lee Gesmer | Apr 7, 2014 | Copyright

Can a state court order assignment of a defamatory posting on Ripoff Report to a prevailing plaintiff?

That may be the central question in Small Justice LLC, et al. v. Xcentric Ventures LLC, pending the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

Here are the basic facts.

A Boston attorney* was defamed by a litigation adversary on the Ripoff Report (a website owned by Xcentric Ventures). The former adversary party, Richard Dupont, claimed that the lawyer was a perjurer with “a history of persecuting the elderly, especially, wealthy elderly women.” The lawyer was accused of filing “baseless lawsuits in order to seize assets from clients, from adversaries and even from his own family.” The posting urged readers to contact the FBI and the Securities and Exchange Commission with similar complaints, and claimed that the attorney had “a history of child abuse, domestic violence and bi-sexuality,” as well as an “addiction to illicit substances.” None of this is true.

*note: The lawyer is not named in this post, to minimize further negative publicity.

The lawyer brought suit against Dupont in Massachusetts state court, where he obtained a default judgment. However, this did him no good as far as the defamatory post was concerned. Ripoff Report is infamous for refusing to remove third-party postings, and the Communications Decency Act (“CDA”) (47 USC § 230) renders it almost impervious to suit by victims of third-party defamation, such as the lawyer victimized in this case.

The lawyer, however, attempted a clever work-around to avoid what he knew would be Ripoff Report’s CDA defense. As part of the remedy in state court the judge assigned to an LLC created by the lawyer — Small Justice LLC — the copyright in the defamatory posting. Small Justice, the copyright owner, then demanded that Ripoff Report take down the copyrighted material. Ripoff Report refused, and Small Justice sued Ripoff Report in federal court in Boston for copyright infringement (and libel, interference with contract, and violations of Massachusetts’ unfair competition statute).

Ripoff Report moved to dismiss (memo in support here), and Judge Denise Casper issued a decision on the motion on March 24, 2014 (Order here).

As the decision implies, however, Ripoff Report may have anticipated Small Justice’s copyright strategy. Ripoff Report’s terms of service required Dupont to check a box before posting his report, granting Ripoff Report an irrevocable license to display the post, as follows:

By posting information or content to any public area of www.RipoffReport.com, you automatically grant, and you represent and warrant that you have the right to grant, to Xcentric an irrevocable, perpetual, fully-paid, worldwide exclusive license to use, copy, perform, display and distribute such information and content and to prepare derivative works of, or incorporate into other works, such information and content, and to grant and authorize sublicenses of the foregoing.

Relying on this license, Ripoff Report argued that whatever rights Small Justice acquired from Dupont by reason of the state court transfer of ownership were subject to the license Dupont granted to Ripoff Report.

Judge Casper did not totally buy this argument, at least at the motion to dismiss stage. Relying on Specht v. Netscape Comm’ns Corp., 306 F.3d 17 (2d Cir. 2002) and Craigslist Inc. v. 3Taps Inc., 942 F. Supp. 2d 962 (N.D. Cal. 2013), Judge Casper held that:

Whether [the quoted paragraph] . . . was sufficient to transfer the copyrights in the Reports from Dupont to Xcentric depends on whether it was reasonable to expect that Dupont would have understood he was conveying those rights to Xcentric. … the Court cannot resolve the issue of the ownership of the copyrights on the present record. Although the process by which users posted to the Ripoff Report appears to be similar to the … context in Specht, the Court cannot say, on this record now before it, what a reasonably prudent offeree in Dupont’s position would have concluded about license.

Accordingly, the motion to dismiss the copyright claim was denied.

Admittedly, the outcome in this case is offensive.* The fact that a person can be defamed in this manner, and that Ripoff Report can use the CDA and contract law to render itself immune from suit, is appalling, at least on first impression (whether the defamed attorney would want to represent anyone naive enough to believe Dupont’s obviously bogus post might be a question worth asking).

*note: An editorial in Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly opined, “[the lawyer] is unquestionably pushing the envelope, but the Ripoff Report’s response to his libel suit makes clear that it’s time for a fresh approach to the growing problem of gratuitous attacks in online reviews. Casper should reject the defense’s motion to dismiss and allow his suit to go forward.”

Hopefully, Judge Casper’s decision will lead to a settlement in which the offending post is removed. However, Xcentric may feel it needs to litigate this case to conclusion to maintain the integrity of the (thus far successful) legal barrier it has created against liability. If that proves to be the case, the law and the facts in this case seem, unfortunately, to favor Xcentric.

Small Justice LLC, et al. v. Xcentric Ventures LLC, 2014 WL 1214828 (D. Mass. Mar. 24, 2014).

Update: Click here for the court’s 2015 summary judgment decision in this case.

by Lee Gesmer | Mar 20, 2014 | Copyright, DMCA/CDA

According to my count, I’ve written seven posts on the Viacom v. Youtube DMCA copyright case. The first time I mentioned Youtube and the DMCA was in October 2006, over 7 years ago. Referencing Mark Cuban’s comment that Youtube would be “sued into oblivion” I stated:

Surprisingly few observers have asked the pertinent question here: do the Supreme Court’s 1995 Grokster decision and the DMCA (the Digital Millennium Copyright Act) protect YouTube from liability for copyright-protected works posted by third parties . . ..?

In fact, Youtube was acquired by Google for $1.65 billion. It was then sued by a group of media companies, resulting in a marathon lawsuit that never went to trial, but yielded two district court decisions and one Second Circuit decision on the issues I identifed in 2006. As I described in a two-part post in December 2013/January 2014, the second appeal to the Second Circuit had been fully briefed and was awaiting oral argument. Now the case has settled, on confidential terms of course. However, demonstrating the extent to which the interests of the media companies and Youtube have converged, the joint press release contained the unusual statement that the “settlement reflects the growing collaborative dialogue between our two companies on important opportunities, and we look forward to working more closely together.”

We may never know the terms of the settlement, but rumor has it that the plaintiffs received no money in this settlement. My guess is they recovered a token amount, if anything. All three decisions favored Youtube, and Viacom’s case had been whittled down to next to nothing, even if it had been able to persuade the Second Circuit to crack the door a bit and remand the case a second time for damages on a limited number of video clips.

However, the settlement leaves some important questions unanswered:

- Viacom’s argument that web sites don’t have to take any actions to “induce infringement” – that this basis for liability can be found based on the owner’s intent or state of mind alone – remains unresolved. This is the Grokster issue I identified in 2006. While I think Viacom’s argument was weak, it would have been helpful to have the Second Circuit resolve it.

- Since the Second Circuit’s first ruling in April 2012 the courts have read the decision to reduce protection for web sites. Courts in New York applying the Second Circuit decision have held that a website can lose DMCA protection if it becomes aware of a specific infringement, or if it is aware of facts that would make it “obvious to a reasonable person” that a specific clip is infringing. Because the case has settled, the Second Circuit will have no opportunity to clarify this standard, at least in this case.

- The Second Circuit will have no opportunity to clarify the “actual knowledge”/”facts or circumstances” sections of the DMCA. The distinction between these two provisions remains confusing to the lower courts and to lawyers who must advise their clients under this law.

- The Second Circuit will have no opportunity to clarify its controversial comments (in its first decision) on “willful blindness,” and help the courts reconcile this concept with the DMCA’s notice-and-takedown procedure. As noted above, the settlement leaves in place the Second Circuit’s implication that awareness of specific infringement may result in infringement liability even in the absence of a take-down notice.

It’s likely that other cases presenting these issues will make their way to the Second Circuit (arguably the nation’s most influential copyright court), but it could be years before that happens. The industry could have used additional guidance in the meantime, and one consequence of this settlement is that it will get it later rather than sooner, if at all.

by Lee Gesmer | Feb 26, 2014 | Copyright

An old legal saw warns that “hard cases make bad law.” The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decision in Garcia v. Google may be a good example of this maxim.

The issue facing the Ninth Circuit was whether an actress can claim a copyright interest in her performance in a film and, if so, under the unusual circumstances in this case, whether the actress could use that copyright to compel Google to remove the film from Youtube.

The facts in this case were very hard. The plaintiff, Cindy Garcia (pictured on left) was paid $500 to act in an independent film for a few days. She was told she was acting in an adventure film set in ancient Arabia. However, the film turned out to be an anti-Islamic movie, and her voice was overdubbed so that she appeared to be asking, “is your Mohammed a child molester?” The movie, titled “Innocence of Muslims,” let to a fatwa, and Garcia received death threats.

After Youtube (owned by Google) refused Garcia’s request to takedown the film (rejecting multiple DMCA notices from Ms. Garia), she brought suit for copyright infringement, make a novel legal argument. Rather than arguing that the film was a joint work under copyright law (which might have entitled her to a share of profits, but wouldn’t have achieved her goal of forcing Youtube to remove the film), she argued that she retained a copyright interest in her contribution. Calling this “a rarely litigated question,” Chief Judge Alex Kosinski, writing for a divided 3-judge panel, avoided the question whether Garcia qualified as a joint author of the film (it seems clear that, under Ninth Circuit precedent such as the Aalmuhammed case, she would not). Instead, he wrote that “nothing in the Copyright Act suggests that a copyright interest in a creative contribution to a work simply disappears because the contributor doesn’t qualify as a joint author of the entire work.”

After Youtube (owned by Google) refused Garcia’s request to takedown the film (rejecting multiple DMCA notices from Ms. Garia), she brought suit for copyright infringement, make a novel legal argument. Rather than arguing that the film was a joint work under copyright law (which might have entitled her to a share of profits, but wouldn’t have achieved her goal of forcing Youtube to remove the film), she argued that she retained a copyright interest in her contribution. Calling this “a rarely litigated question,” Chief Judge Alex Kosinski, writing for a divided 3-judge panel, avoided the question whether Garcia qualified as a joint author of the film (it seems clear that, under Ninth Circuit precedent such as the Aalmuhammed case, she would not). Instead, he wrote that “nothing in the Copyright Act suggests that a copyright interest in a creative contribution to a work simply disappears because the contributor doesn’t qualify as a joint author of the entire work.”

The opinion concludes that Ms. Garcia may claim a copyright interest in “the portion of the film that represents her individual creativity.”

The court rejected Google’s argument that Ms. Garcia’s performance was a work made for hire (she was not an employee), or that she had granted the filmmaker an implied license (her participation had been induced by fraud, precluding that argument). And, Ms. Garcia had never assigned her rights to the filmmaker in a written document.

Lastly, the court found that Ms. Garcia had suffered irreparable harm (“death is an irremediable harm, and bodily injury is not far behind”), and that she had satisfied the causation requirement. The court “rejected Google’s preposterous argument that any harm to Garcia is traceable to her filing of this lawsuit.”

The district court had denied an injunction, which the Ninth Circuit reversed, ordering Youtube to take down all copies of “Innocence of Muslims.”

It’s difficult to predict whether this case will be a significant legal precedent. The idiosyncratic facts were sympathetic to Ms. Garcia, who appears to have been the victim of a fraudulent filmmaker, and who suffered unusual harm as a consequence. However, independent of these facts, the Ninth Circuit has held that an actor or actress owns an independent copyright interest in a film performance, reminding every non-fraudulent film producer to obtain a written copyright assignment from every performer.

Garcia v. Google, Inc. (9th Cir., February 26, 2014)

by Lee Gesmer | Feb 25, 2014 | Copyright

[Catch-up Post] In an unusual application of the copyright fair use doctrine, on January 27, 2014, the Second Circuit held that Bloomberg’s copy of an investor conference call by Swatch was protected from copyright infringement under the fair use doctrine.

The facts are unusual. Swatch transmittd, recorded and promptly registered the copyright for a 2011 earnings call. Bloomberg recorded the call separately. Swatch claimed that Bloomberg’s recording infringed Swatch’s recording.

Although, technically speaking, Bloomberg did not copy Swatch’s copy of the call (it recorded it simultaneously, an issue I’ll return to below), the district court judge based his decision of non-infringement on fair use and the Second Circuit affirmed.

Analyzing fair use utilizing the four statutory fair use factors,* the Second Circuit held that Bloomberg’s purpose was to deliver important financial information to investors, and that this was analogous to news reporting, an activity often favored under the fair use doctrine. The fact that Bloomberg’s reproduction was not transformative was not an obstacle to a finding of fair use since, as the Second Circuit said, cases of news reporting favor “faithfully reproduc[ing] an original work rather than transform[ing] it.”

*note: Abbreviated, the factors are (1) the purpose and character of the use;(2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market fo the copyrighted work. 17 U.S.C. 107.

Second, while the work was technically unpublished under the Copyright Act’s definition of “publication,” a fact that usually cuts against fair use, the court held that because the contents of the recording were transmitted during the conference call, “the publication status of the work favors fair use.” Third, although Bloomberg copied the entire recording (again, a factor that typically weighes against fair use), it didn’t help Swatch in this context. The court held that “copying the entirety of a work is sometimes necessary to make a fair use,” and that was the case here.

Fourth, the Second Circuit held that the fact that there is no commercial market for the resale of financial earnings calls favored fair use.

Swatch v. Bloomberg is a significant case in the evolution of fair use case law, which has been quite active as of late (see, for example, Google Books, Cariou v. Prince).

It’s worth pointing out that the Second Circuit dodged an unusual copyright issue on this appeal. One of the fundamental precepts of copyright law is that the work for which copyright is claimed must be “fixed in a tangible medium of expression,” such as a book, film or a digital storage device. In this case Swatch’s audio was recorded simultaneously with its transmission, satisfying the all-important “fixation” requirement. However, Bloomberg received the transmission simultaneously with Swatch’s receipt and fixation of the call, and therefore fixation had not taken place at the instant Bloomberg made its recording. Accordingly, Bloomberg argued, no copyright-protected work existed at the moment Bloomberg recorded the transmission.

This issue was addressed in the lower court opinion, decided in April 2011. Swatch’s response, which the federal district court accepted, relied on Section 101 of the Copyright Act, part of which states that “a work consisting of sounds, images, or both, that are being transmitted, is ‘fixed’ for purposes of this title if a fixation of the work is being made simultaneously with its transmission.” The district court applied this section of the statute, and held that copyright law creates a legal fiction that the simultaneous fixation occurs before the transmission. This ruling allows the unauthorized recording of sounds that are transmitted live and recorded simultaneously to be the subject of a copyright infringement claim.

Bloomberg sought to challenge this interpretation of the copyright statute on appeal, but the Second Circuit refused to address the issue based on a procedural defect in Bloomberg’s appeal. This leaves the lower court decision on a rare and obscure issue of copyright law intact.

The Swatch Group Mgt. Services Ltd. v. Bloomberg, L.P. (2nd Cir. Jan.27, 2014)

by Lee Gesmer | Feb 21, 2014 | Copyright

It’s difficult to believe that so many judges and lawyers could disagree over what would appear, at first blush, to be a straightforward issue of copyright law. Can a company legally copy over-the-air TV broadcasts and transmit them to subscribers over the Internet, as long as it stores and transmits a separate copy for each customer?

Two companies have adopted this technology,, Aereo and FilmOn X (fka “BarryDriller.com”). Two federal courts have held that this does  not violate the copyright rights of broadcasters (New York’s Second Circuit and a Massachusetts district court), and three courts have held it does (the California, D.C. and Utah district courts). Thus far, all of the rulings have arisen in the context of preliminary injunction motions, and until the Utah court’s ruling on February 19, 2014, Aereo had survived two challenges (New York and Massachusetts). FilmOn X had suffered the two losses (California and D.C.). Before the Utah decision, the Supreme Court had accepted review of the New York case, an unusual development given the fact that none of these cases involved a final judgment on the merits.

not violate the copyright rights of broadcasters (New York’s Second Circuit and a Massachusetts district court), and three courts have held it does (the California, D.C. and Utah district courts). Thus far, all of the rulings have arisen in the context of preliminary injunction motions, and until the Utah court’s ruling on February 19, 2014, Aereo had survived two challenges (New York and Massachusetts). FilmOn X had suffered the two losses (California and D.C.). Before the Utah decision, the Supreme Court had accepted review of the New York case, an unusual development given the fact that none of these cases involved a final judgment on the merits.

The Utah decision may prove to have tipped the balance, in more ways than one. Not only is the count now 3-2 in favor of the broadcasters in judging the legality of the “individual copies” technology, but Utah Federal District Court Judge Dale Kimball — a 17 year judicial veteran and former law professor — may have finally cut through the massive volume of verbiage surrounding this issue.

The section of the Copyright Act at issue, the “Transmit Clause,” states:

To perform or display a work “publicly” means—

to transmit or otherwise communicate a performance or display of the work … by means of any device or process, whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times.

When confronted with the same issue that had been presented to four federal district courts and the Second Circuit, and which will be decided by the Supreme Court this term, Judge Kimball made short work of the local broadcaster’s motion for a preliminary injunction:

The plain language of the 1976 Copyright Act support Plaintiffs’ position. The definitions in the Act contain sweepingly broad language and the Transmit Clause easily encompasses Aereo’s process of transmitting copyright-protected material to its paying customers. Aereo uses “any device or process” to transmit a performance or display of Plaintiff’s copyrighted programs to Aereo’s paid subscribers, all of whom are members of the public, who receive it in the same place or separate places and at the same time or separate times.

After recapping the legislative history of the Transmit Clause, Judge Kimball stated:

Aereo’s retransmission of Plaintiffs’ copyrighted programs is indistinguishable from a cable company and falls squarely within the language of the Transmit Clause. It is undisputed that Plaintiffs license its programming to cable and satellite television companies and through services such as Hulu and iTunes. These companies and services are providing paying customers with retransmissions of copyrighted works. Similarly, Aereo uses “any device or process” to transmit a performance or display of Plaintiff’s copyrighted programs to Aereo’s paid subscribers, all of whom are members of the public.

Judge Kimball was not impressed with the reasoning of the Second Circuit in the Cablevision case (Cartoon Network v. CSC Holdings), the 2008 case that created the copyright “loophole” on which Aereo and FilmOn X have built their businesses:

To reach its conclusion that the recorded copies for later playback did not require an additional license as a separate public performance, the Second Circuit proceeded to spin the language of the Transmit Clause, the legislative history, and prior case law into a complicated web. The court focused on discerning who is “capable of receiving” the performance to determine whether a performance is transmitted to the public. However, such a focus is not supported by the language of the statute. The clause states clearly that it applies to any performance made available to the public. Paying subscribers would certainly fall within the ambit of “a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances” and within a general understanding of the term “public.”

However, the Cablevision court appears to discount the simple use of the phrase “to the public” because it concludes that the final clause within the Transmit Clause – “whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times”– was intended by Congress to distinguish between public and private transmissions. This court disagrees. The entire clause “whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times” appears to actually be Congress’ attempt to broaden scope of the clause, not an effort to distinguish public and private transmissions or otherwise limit the clause’s reach. The term “whether” does not imply that the ensuing clause encompasses a limitation. Rather, the introduction of the clause with the word “whether” implies an intent to explain the broad sweep of the clause and the many different ways it could apply to members of the public. Reading this final clause expansively is consistent with Congress’ intent to have the entire Transmit Clause apply to all technologies developed in the future.

Judge Kimball challenged an interpretation of the law that lies at the very heart of the Cablevision decision:

The Cablevision court’s analysis also appears to have changed the wording of the Transmit Clause from reading “members of the public capable of receiving the performance” to “members of the public capable of receiving the transmission.” Therefore, instead of examining whether the transmitter is transmitting a performance of the work to the public, the Cablevision court examined who is capable of receiving a particular transmission. This court agrees with Plaintiffs that the language of the Transmit Clause does not support such a focus.

Judge Kimball concluded that:

Based on the plain language of the 1976 Copyright Act and the clear intent of Congress, this court concludes that Aereo is engaging in copyright infringement of Plaintiffs’ programs. Despite its attempt to design a device or process outside the scope of the 1976 Copyright Act, Aereo’s device or process transmits Plaintiffs’ copyrighted programs to the public.

Based on this analysis the court enjoined Aereo from providing its service in the six states in the Tenth Circuit (Colorado, Kansas, New  Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah and Wyoming). He declined to stay the injunction pending the Supreme Court’s review of the issue, ordering that the preliminary injunction go into force at once.

Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah and Wyoming). He declined to stay the injunction pending the Supreme Court’s review of the issue, ordering that the preliminary injunction go into force at once.

This case, and the fact that it is Aereo’s first courtroom loss, just adds to the drama over the upcoming Supreme Court hearing and decision on this issue. Will the Supreme Court perceive the issue to be a simple as Judge Kimball, or will it, to use Judge Kimball’s phrase, “spin the language” of the Transmit Clause to come out the same way as the Second Circuit ?

And, while this line of cases may be of academic interest to copyright lawyers, it is of immense practical interest to untold numbers of consumers who may want to use the Aereo/FilmOn X services to help them “cut the cord” of the expensive cable services. For this reason, pressure on the Supreme Court from consumer rights advocates in favor of Aereo’s technology is likely to be intense. The extent to which this will influence the Supreme Court may never be known, but few will deny that it will be a factor.

by Lee Gesmer | Feb 11, 2014 | Copyright, DMCA/CDA

A couple of weeks ago I returned to the offices of the URBusiness Network to discuss the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). This was my second trip to the URBusiness Network, an online radio network with a wide range of business shows.

The subject of the first show, recorded last October, was web site liability for third party postings under the Communications Decency Act (CDA). However, the CDA does not protect web sites for user postings that violate copyright law, so copyright liability and the DMCA were the topics of the current show.

Once again it was a pleasure to be interviewed by Ruck Brutti, who was joined on this occasion by co-host Nathan Roman.

You can listen to the new show here.

father Frank Petrella’s copyright interest in a book and two screenplays about the life of Jake LaMotta, the central character portrayed in the film Raging Bull. She asserts that Raging Bull is a derivative work of the book and screenplays, and that she is entitled to royalties based on MGM’s distribution of the film during the three years preceding her suit.

father Frank Petrella’s copyright interest in a book and two screenplays about the life of Jake LaMotta, the central character portrayed in the film Raging Bull. She asserts that Raging Bull is a derivative work of the book and screenplays, and that she is entitled to royalties based on MGM’s distribution of the film during the three years preceding her suit. courts interpret and apply the decision. For example, given the Supreme Court’s comments it is uncertain that Ms. Petrella will be able to obtain an injunction against future sales of Raging Bull, and the Court’s statement that a delay in bringing suit is relevant to determining damages based on MGM’s profits during the three year period may limit any recovery by allowing MGM to use its investment in the film prior to the three-year look-back period to offset profits earned during those three years. Therefore, the extent of any potential monetary recovery is unclear.

courts interpret and apply the decision. For example, given the Supreme Court’s comments it is uncertain that Ms. Petrella will be able to obtain an injunction against future sales of Raging Bull, and the Court’s statement that a delay in bringing suit is relevant to determining damages based on MGM’s profits during the three year period may limit any recovery by allowing MGM to use its investment in the film prior to the three-year look-back period to offset profits earned during those three years. Therefore, the extent of any potential monetary recovery is unclear.

After Youtube (owned by Google) refused Garcia’s request to takedown the film (rejecting multiple DMCA notices from Ms. Garia), she brought suit for copyright infringement, make a novel legal argument. Rather than arguing that the film was a joint work under copyright law (which might have entitled her to a share of profits, but wouldn’t have achieved her goal of forcing Youtube to remove the film), she argued that she retained a copyright interest in her contribution. Calling this “a rarely litigated question,” Chief Judge Alex Kosinski, writing for a divided 3-judge panel, avoided the question whether Garcia qualified as a joint author of the film (it seems clear that,

After Youtube (owned by Google) refused Garcia’s request to takedown the film (rejecting multiple DMCA notices from Ms. Garia), she brought suit for copyright infringement, make a novel legal argument. Rather than arguing that the film was a joint work under copyright law (which might have entitled her to a share of profits, but wouldn’t have achieved her goal of forcing Youtube to remove the film), she argued that she retained a copyright interest in her contribution. Calling this “a rarely litigated question,” Chief Judge Alex Kosinski, writing for a divided 3-judge panel, avoided the question whether Garcia qualified as a joint author of the film (it seems clear that,

not violate the copyright rights of broadcasters (New York’s Second Circuit and a Massachusetts district court), and three courts have held it does (the California, D.C. and Utah district courts). Thus far, all of the rulings have arisen in the context of preliminary injunction motions, and until the Utah court’s ruling on February 19, 2014, Aereo had survived two challenges (New York and Massachusetts). FilmOn X had suffered the two losses (California and D.C.). Before the Utah decision, the Supreme Court had accepted review of the New York case, an unusual development given the fact that none of these cases involved a final judgment on the merits.

not violate the copyright rights of broadcasters (New York’s Second Circuit and a Massachusetts district court), and three courts have held it does (the California, D.C. and Utah district courts). Thus far, all of the rulings have arisen in the context of preliminary injunction motions, and until the Utah court’s ruling on February 19, 2014, Aereo had survived two challenges (New York and Massachusetts). FilmOn X had suffered the two losses (California and D.C.). Before the Utah decision, the Supreme Court had accepted review of the New York case, an unusual development given the fact that none of these cases involved a final judgment on the merits.