by Lee Gesmer | Mar 6, 2023 | Copyright

There are a number of computer programs and websites that will allow you to create an image using artificial intelligence. One of them is Midjourney. You can see some of the Midjourney AI-generated art here.

Kris Kashtanova used Midjourney’s generative AI tool to create a comic book titled Zarya of the Dawn. She submitted the work to the Copyright Office, seeking registration, and the Office issued the registration in September 2022. However according to the Copyright Office Ms. Kashtanova did not disclose that she used artificial intelligence to create Zarya.

Soon afterwards the Office became aware – via a reporter’s inquiry and social media posts – that Ms. Kashtanova had created the comic book using artificial intelligence. The Office reconsidered the registration and, after much correspondence and argumentation with Ms. Kashtanova’s attorneys, canceled the registration, concluding that:

. . . the images in the Work that were generated by the Midjourney technology are not the product of human authorship. Because the current registration for the Work does not disclaim its Midjourney-generated content, we intend to cancel the original certificate issued to Ms. Kashtanova and issue a new one covering only the expressive material that she created.

Image from Zarya

This conclusion is the denouement in a lengthy letter from the Copyright Office analyzing the copyrightability of the images contained in the Zarya comic in detail in light of how Midjourney creates images. In correspondence with the Copyright Office Ms. Kashtanova argued that she had provided “hundreds or thousands of descriptive prompts” to Midjourney to generate “as perfect a rendition of her vision as possible.” However, based on how Midjourney creates images – essentially via a random mechanical process, notwithstanding the prompts of the human “mastermind” – the Copyright Office concluded that she was not the “author” of the resulting images for copyright purposes. The Copyright Office reasoned that “unlike other tools used by artists” (such as Adobe Photoshop), Midjourney generates images using prompts in an “unpredictable way.” “Because of the significant distance between what a user may direct Midjourney to create and the visual material Midjourney actually produces,” Ms. Kashtanova did not have enough control over the final images generated to be the “inventive or mastermind” behind the images.

Here are some takeaways from this decision.

First, artists using generative AI to create images should not assume that they own a copyright in the images. At present the Copyright Office appears firmly committed to its position that they do not, and until there are court decisions to the contrary, or Congress amends the Copyright Act to accommodate these works, the better practice is to assume no protection.

Second, it may be possible to protect an AI-created work based on human modifications to the work. This was illustrated by the Zarya decision, where Ms. Kashtanova also sought registration for images that she created using Midjourney but altered post-production using Photoshop. With respect to one of these images the Copyright Office left open the possibility that copyrightable expression had been added, and therefore the image might receive registration. However, in these cases the burden will be on the human artist to establish that the human modifications or contributions reflect sufficient expression to receive protection. And, the scope of protection would likely be limited to the modifications, not the full image.

Image from Zarya

Third, this is a fast-moving area of law. Ms. Kashtanova – or any person or company denied registration – has the right to appeal the Copyright Office’s decision to a federal district court, from which the case may go on appeal to a circuit court, or even the Supreme Court. Whether Ms Kashtanova will take that action – or whether we will have to wait for another case – remains to be seen. A court – or Congress by amendment to the Copyright Act – could change the law on copyright protection of AI images.

Lastly, the Copyright Office’s reasoning on AI images is likely to extend to text as well. Thus, if a person uses a program such as ChatGPT to create a written work, it seems unlikely that the Copyright Office would accept it for purposes of registration. Despite the best efforts of the “prompt engineer,” the resulting output is likely to be too random to fall within the Copyright Office’s views of authorship.

Update: On March 10, 2023, less than a week after I published this post, the Copyright Office issued a “statement of policy to clarify its practices for examining and registering works that contain material generated by the use of artificial intelligence technology.” (link). Here is the heart of that policy statement: “In the case of works containing AI-generated material, the Office will consider whether the AI contributions are the result of ‘mechanical reproduction’ or instead of an author’s ‘own original mental conception, to which [the author] gave visible form.’ The answer will depend on the circumstances, particularly how the AI tool operates and how it was used to create the final work. This is necessarily a case-by-case inquiry.”

How this principle will be applied in practice remains to be seen.

by Lee Gesmer | Mar 2, 2023 | Contracts, General, Technology

I asked GPT 3.5 to create a license agreement using the following prompt:

Draft an End user object code software license agreement between LICENSOR and LICENSEE using the following terms.

• Formal delivery, acceptance testing, final acceptance within 30 days assumed unless notice within that period

• A site license limited to offices in Cambridge, MA

• The licensor will provide updates annually

• License should be limited to internal use; resale/redistribution prohibited

• The software should be treated as confidential

• The terms of this license agreement must be confidential

• The agreement is subject to Massachusetts law.

• Annual license fee $100,000, increased annually by 5%.

• Price exclusive of applicable taxes

• Term: five years

• Any dispute subject to arbitration, venue in Massachusetts, three person panel with SAAS subject matter expertise

• Agreement is non-assignable

• Agreement is terminable for non-payment; licensee may cure within 30 days notice of default

• Limited warranty in accordance with specifications. Exclusive remedy is damages limited to monies paid by Licensee

• No virus warranty

• Non-infringement warranty

• No claims pending warranty

• No implied warranty or warranty for specific purpose

• Indemnification against IP claims – yes

• Source code escrow accessible in event of material breach by Licensor

• Licensee may not reverse engineer

• Notices in writing – certified mail

• Any amendment must be in writing

Here is the agreement the AI created. What do you think?

________________________________

SOFTWARE LICENSE AGREEMENT

This Software License Agreement (“Agreement”) is made and entered into as of the date of acceptance by Licensee, by and between Licensor, and Licensee.

1. DEFINITIONS.

(a) “Software” means the object code form of the software products specified in the applicable order form or purchase order, and any related documentation, materials, updates, and upgrades provided by Licensor to Licensee under this Agreement.

(b) “Order Form” means the written or electronic document issued by Licensor and executed by both Licensor and Licensee, or submitted electronically by Licensee and accepted by Licensor, specifying the Software licensed by Licensee and any related services.

(c) “Documentation” means the user manuals, installation guides, and other technical documentation provided by Licensor to Licensee.

(d) “Licensee” means the individual or entity that accepts the terms and conditions of this Agreement.

(e) “Licensor” means the individual or entity that licenses the Software to Licensee under this Agreement.

(f) “Support Services” means the support and maintenance services described in Section 5 of this Agreement.

(g) “Confidential Information” means any information disclosed by either party to the other party, either directly or indirectly, in writing, orally, or by inspection of tangible objects, which is designated as “Confidential,” “Proprietary,” or some similar designation, or which should reasonably be understood to be confidential given the nature of the information and the circumstances of disclosure.

2. GRANT OF LICENSE.

(a) Subject to the terms and conditions of this Agreement, Licensor hereby grants to Licensee a non-exclusive, non-transferable license to use the Software and Documentation, solely for Licensee’s internal business purposes, and only at Licensee’s offices in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

(b) Licensee shall not use the Software or Documentation for any purpose other than as expressly permitted by this Agreement.

(c) Licensee shall not modify, copy, reproduce, distribute, or create derivative works of the Software or Documentation.

(d) Licensee shall not remove or alter any proprietary notices or labels on the Software or Documentation.

(e) Licensee shall not disclose or distribute the Software or Documentation to any third party without the prior written consent of Licensor.

3. DELIVERY.

(a) Licensor shall deliver the Software and Documentation to Licensee within thirty (30) days after the date of execution of the Order Form.

(b) Licensee shall have a period of thirty (30) days following delivery to conduct acceptance testing of the Software and Documentation.

(c) Licensee shall notify Licensor in writing within thirty (30) days of delivery if Licensee determines that the Software or Documentation fails to meet the specifications set forth in the Order Form.

(d) If Licensee does not provide written notice of non-acceptance to Licensor within thirty (30) days after delivery, the Software and Documentation shall be deemed accepted by Licensee.

4. UPDATES.

(a) Licensor shall provide updates to the Software and Documentation annually during the term of this Agreement, at no additional charge.

(b) Licensee shall be entitled to install and use such updates during the term of this Agreement.

(c) Licensee shall not use any updates to the Software or Documentation in any manner that violates the terms of this Agreement.

5. SUPPORT SERVICES.

(a) Licensor shall provide Support Services to Licensee during the term of this Agreement, at no additional charge.

(b) Support Services shall include:

(i) Telephone and email support for Licensee’s designated technical support personnel during Licensor’s normal business hours;

(ii) Bug fixes and updates to the Software as necessary to correct material errors or malfunctions that materially affect the Software’s operation in accordance with the Documentation;

(iii) Assistance with installation, configuration, and troubleshooting of the Software;

(iv) Access to online support resources, including user forums and knowledge bases; and

(v) Any other support services agreed to by the parties in writing.

(c) Licensor shall not be obligated to provide Support Services if:

(i) The Software or Documentation has been modified, altered, or tampered with by anyone other than Licensor;

(ii) The Software or Documentation has been used in a manner not authorized by this Agreement;

(iii) The failure of the Software to operate is due to causes outside of Licensor’s control, including but not limited to failure of Licensee’s hardware or software systems; or

(iv) Licensee has not paid any applicable fees when due.

6. FEES.

(a) Licensee shall pay Licensor an annual license fee of $100,000, exclusive of any applicable taxes.

(b) The annual license fee shall be increased by five percent (5%) at the beginning of each subsequent year of the term of this Agreement.

(c) Licensee shall pay all fees within thirty (30) days of the date of the applicable invoice.

(d) Licensor reserves the right to suspend or terminate Licensee’s access to the Software and Support Services if Licensee fails to pay any fees when due.

7. TERM AND TERMINATION.

(a) This Agreement shall commence on the date of acceptance by Licensee and shall continue for a term of five (5) years.

(b) Either party may terminate this Agreement upon written notice if the other party materially breaches any provision of this Agreement and fails to cure such breach within thirty (30) days after receiving written notice of such breach.

(c) Licensor may terminate this Agreement immediately if Licensee fails to pay any fees when due.

(d) Upon termination of this Agreement, Licensee shall immediately cease all use of the Software and Documentation, and shall return or destroy all copies of the Software and Documentation in Licensee’s possession or control.

(e) The provisions of Sections 2(d), 2(e), 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13 shall survive any termination or expiration of this Agreement.

8. WARRANTIES AND DISCLAIMERS.

(a) Licensor represents and warrants that it has the right to license the Software to Licensee, and that the Software does not infringe any third party’s intellectual property rights.

(b) Licensor warrants that the Software will materially conform to the specifications set forth in the Order Form and the Documentation.

(c) Licensee’s exclusive remedy for any breach of the warranties set forth in this Section 8 shall be for Licensor to use commercially reasonable efforts to correct or replace the non-conforming Software or Documentation, or if Licensor is unable to do so within a reasonable period of time, to refund the fees paid by Licensee for the non-conforming Software or Documentation.

(d) Licensor does not warrant that the Software or Documentation will be error-free or uninterrupted.

(e) Licensor makes no warranties, express or implied, regarding the Software or Documentation, including but not limited to any implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement.

(f) Licensee acknowledges that it has not relied on any representations or warranties not expressly set forth in this Agreement.

9. INDEMNIFICATION.

(a) Licensor shall indemnify, defend, and hold harmless Licensee from and against any and all claims, damages, liabilities, costs, and expenses (including reasonable attorneys’ fees) arising out of or related to any third party claim that the Software infringes any third party’s intellectual property rights.

(b) Licensee shall promptly notify Licensor in writing of any claim covered by this Section 9, and Licensor shall have sole control over the defense and settlement of any such claim. Licensee shall provide Licensor with all necessary assistance, information, and authority to perform such defense or settlement.

(c) If any claim covered by this Section 9 arises or is likely to arise, Licensor may, at its sole option and expense:

(i) Obtain for Licensee the right to continue using the Software;

(ii) Modify the Software so that it becomes non-infringing;

(iii) Replace the Software with non-infringing software that is functionally equivalent;

(iv) Terminate this Agreement and refund the fees paid by Licensee for the infringing Software; or

(v) Defend Licensee against the claim.

(d) Licensor shall have no liability under this Section 9 to the extent that the claim is based on:

(i) Any modification of the Software or Documentation by anyone other than Licensor;

(ii) The combination of the Software with any product, service, or process not provided by Licensor, to the extent that such claim would not have arisen but for such combination; or

(iii) Licensee’s failure to use the Software or Documentation in accordance with this Agreement or the Documentation.

10. LIMITATION OF LIABILITY.

(a) In no event shall Licensor be liable to Licensee for any indirect, incidental, consequential, special, or punitive damages, including but not limited to lost profits, loss of business, or loss of data, arising out of or related to this Agreement, even if Licensor has been advised of the possibility of such damages.

(b) Licensor’s total liability to Licensee for all claims arising out of or related to this Agreement shall be limited to the fees paid by Licensee to Licensor under this Agreement during the twelve (12) month period preceding the claim.

11. CONFIDENTIALITY.

(a) Licensee acknowledges that the Software and Documentation contain valuable trade secrets and confidential information of Licensor.

(b) Licensee shall use the same degree of care to protect the confidentiality of the Software and Documentation as it uses to protect its own confidential information, but in no event less than a reasonable degree of care.

(c) Licensee shall not disclose the Software or Documentation to any third party without the prior written consent of Licensor.

(d) The terms of this Agreement shall be deemed Confidential Information of both parties.

(e) This Section 11 shall survive any termination or expiration of this Agreement.

12. ARBITRATION.

(a) Any dispute, claim, or controversy arising out of or related to this Agreement shall be resolved by binding arbitration in accordance with the rules of the American Arbitration Association.

(b) The arbitration shall take place in Massachusetts, and the arbitrators shall have experience in the software-as-a-service industry.

(c) The arbitration shall be conducted by a panel of three (3) arbitrators.

(d) The arbitration shall be conducted in the English language.

(e) The decision of the arbitrators shall be final and binding on the parties.

(f) This Section 12 shall not preclude either party from seeking injunctive relief in a court of competent jurisdiction.

13. GENERAL PROVISIONS.

(a) This Agreement constitutes the entire agreement between the parties with respect to the subject matter hereof and supersedes all prior or contemporaneous agreements, representations, warranties, and understandings, whether oral or written.

(b) This Agreement may not be amended except in writing signed by both parties.

(c) Licensee may not assign this Agreement or any rights or obligations hereunder, whether by operation of law or otherwise, without the prior written consent of Licensor.

(d) Licensor may assign this Agreement or any rights or obligations hereunder without the consent of Licensee.

(e) This Agreement shall be binding upon and inure to the benefit of the parties hereto and their respective successors and assigns.

(f) If any provision of this Agreement is held to be invalid or unenforceable, such provision shall be deemed modified to the extent necessary to make it valid and enforceable, and the remaining provisions of this Agreement shall remain in full force and effect.

(g) No failure or delay by either party in exercising any right or remedy hereunder shall operate as a waiver thereof, nor shall any single or partial exercise of any such right or remedy preclude any other or further exercise thereof or the exercise of any other right or remedy.

(h) This Agreement shall be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, without giving effect to its conflict of laws provisions.

(i) Any notices required or permitted to be given hereunder shall be in writing and shall be deemed to have been given and received (i) when delivered by hand, (ii) three (3) business days after being sent by registered or certified mail, return receipt requested, postage prepaid, or (iii) one (1) business day after being sent by nationally recognized overnight courier, to the parties at the addresses set forth below or to such other addresses as either party may specify in writing.

Licensor:

[Insert Licensor’s Name and Address]

Attention: [Insert Name and Title]

Licensee:

[Insert Licensee’s Name and Address]

Attention: [Insert Name and Title]

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the parties have executed this Agreement as of the date first above written.

LICENSOR:

[Insert Licensor’s Name]

By: _____________________________

Name: [Insert Name and Title]

Title: [Insert Title]

LICENSEE:

[Insert Licensee’s Name]

By: _____________________________

Name: [Insert Name and Title]

Title: [Insert Title]

by Lee Gesmer | Feb 17, 2023 | Noncompete Agreements

The Federal Trade Commission would like to preempt state law and make most noncompetes illegal as a matter of nationwide federal law. In January it began a rulemaking toward that end. See The FTC: Noncompete Agreements Must Go.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be looking over your shoulder now. The FTC may be coming for you, especially if you’re a large company that uses noncompetes abusively and without legal justification.

The reason for this is that, in addition to its rulemaking, the FTC has brought several cases charging companies for imposing abusive noncompetes on employees.

Shortly before it issued its notice of proposed rulemaking the FTC announced that it had taken legal action against several companies to stop them from enforcing noncompete restrictions. These cases are the first time that the FTC has filed suit to block noncompete agreements.

It’s no secret that some companies abuse noncompetes – they use them to control low-wage, unskilled employees, where there can be no legal justification for the use of noncompetes. This has caught the attention of the FTC, which contends that the use of noncompetes can violate Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, 15 U.S.C. § 45, which prohibits “unfair methods of competition.”

The FTC initiated two groups of cases.

FTC v. Prudential Security, Inc. (complaint). In this case Prudential, and a related company, required security guards to sign two-year noncompete agreements. The low-wage unskilled employees were subject to a $100,000 liquidated damages clause if they violated the noncompete.

This is the kind of noncompete that gives noncompete agreements a bad name. The security guards are unlikely to possess confidential information or have customer good will – the two justifications for noncompetes. The employees could not negotiate the agreements, and Prudential brought lawsuits to enforce them. It continued to require employees to sign them even after a court declared them unenforceable.

And, I’ve seen a lot of noncompetes, but I’ve never seen one that contains a liquidated damages clause, much less a $100,000 liquidated damages clause.

The FTC alleged that “Any possible legitimate objectives of [Prudential’s] conduct . . . could have been achieved through significantly less restrictive means, including, for example, by entering confidentiality agreements that prohibited disclosure of any confidential information.”

Ardagh Group and O-I Glass. (complaint). FTC complaints against Ardagh Group and O-I Glass – two large glass beverage container manufacturers – followed a similar pattern. Both companies required over 1,000 employees to enter into noncompetes. However, the focus in these cases was the use of noncompetes in concentrated industries, rather than using them against low-wage employees, as in the Prudential cases. In bringing these actions the FTC emphasized that the “glass food and beverage container industry in the United States is highly concentrated,” and “it is difficult for new competitors to enter the market in part because of the need to find and hire people who are skilled and experienced in glass container manufacturing.” (link)

All these companies quickly folded in the FTC actions, entering into Consent Decrees that voided their noncompetes and required them to inform all employees who had entered into noncompetes that they were no longer enforceable. In fact, the FTC announced the cases and the Consent Decrees at the same time.

And, there’s every reason to suspect that the FTC is not done – it’s likely that it is investigating other companies and considering more noncompete enforcement actions. Against this backdrop companies should assess their noncompete agreements and ensure that they are legally justified.

***

Coda: These cases, along with the noncompete rulemaking, have really shaken up things at the FTC. The Commission is composed of five Commissioners. One seat is vacant, and the remaining four seats are held by three Democrats and one Republican. The Democratic Chair is Lina Khan, the outspoken, controversial “hipster” antitrust advocate and author of the influential law review article, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox. The only Republican Commissioner, Christine Wilson, has been an outspoken critic of the Commission’s actions in several enforcement areas, including noncompetes – to the extent that she has announced that she will soon resign from the FTC. Why I’m Resigning As An FTC Commissioner (“This proposed rule defies the Supreme Court’s decision in West Virginia v. EPA (2022), which held that an agency can’t claim ‘to discover in a long-extant statute an unheralded power representing a transformative expansion in its regulatory authority’”).

FTC Cracks Down on Companies That Impose Harmful Noncompete Restrictions on Thousands of Workers

by Lee Gesmer | Feb 7, 2023 | DMCA/CDA

When a traditional print publication – a print newspaper or magazine – publishes a defamatory statement it is “strictly liable” for defamation. This is true even if the statement is written by an an unaffiliated third-party – for example a “letter to the editor.”

But the law for print publications is not the same for Internet websites. A law enacted in 1996, the Communications Decency Act, prohibits courts from treating a provider of an “interactive computer service” i.e., a website, as the “publisher or speaker” of third-party content posted on its platform. 47 U.S.C. 230(c)(1). Under this law, referred to as “Section 230,” websites have been granted broad legal protection. Section 230 has created what is, in effect, a form of legal exceptionalism for Internet publishers. Without it any social media site (such as Facebook, Twitter) or review site (such as Amazon) would have been sued into oblivion.

This law has been criticized and defended vigorously for many years. On the whole, the courts have given the law liberal application, dismissing cases against Internet providers in a wide variety of contexts and under many fact scenarios

However, as I recently noted, for the first time the Supreme Court has agreed to hear a Section 230 case. Supreme Court Will Decide Whether Google’s Algorithm-Based Recommendations are Protected Under Section 230.

Oral argument in the case is rapidly approaching – the Court will hear argument on February 21, 2023. When that day arrives you can listen to it live here.

Although Section 230 has been most effective in shielding websites from defamation claims, the case before the Supreme Court involves a different law. The plaintiffs are the estate and family of Nohemi Gonzalez, an American citizen who was murdered in a 2015 ISIS attack in Paris. Gonzalez’s family and estate argue that Google violated the Antiterrorism Act, 18 U.S.C. 2331, by providing targeted recommendations for Youtube videos posted by ISIS. Ms. Gonzalez’s family asserts that Google violated the ATA by using its algorithms to recommend ISIS videos and spread ISIS’s message on Youtube.

The Ninth Circuit held that Section 230 protected Google from liability.

The plaintiffs appealed, posing the following issue to the Court: “Under what circumstances does the defense created by section 230 apply to recommendations of third-party content?” (link)

While you might think that this is a narrow issue, in the cloistered world of Internet/social media law that is far from true. In those regions this is heady stuff. Section 230 has been an almost insurmountable defensive barrier for Internet publishers, and particularly social media companies. Supporters of a broad application of Section 230 are watching the Gonzalez case with apprehension, fearing that the Court will narrow it. Critics of the law are watching the case with hope that the Court will do just that.

Not surprisingly, the case has attracted an enormous number of amicus briefs. I count a total of 79 briefs. They range from briefs filed by Senators Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz (urging that Section 230 be narrowed) to Meta Platforms (Facebook/Instagram) and Microsoft (urging the Court to apply Section 230 broadly). Pretty much every major social media company has weighed in on this case.

When I look at the docket of a Supreme Court appeal one of the first questions I ask is: has the Solicitor General – who represents the executive branch of the federal government – entered an appearance and filed a brief? And if so, which side has it taken?

The Solicitor General, or “SG” is sometimes referred to as the “Tenth Justice.” Its views on a case are important, sometimes more important than those of the parties. Sometimes the Court invites the SG to take a position on a case, other times the SG enters the case at its own initiative. In Gonzalez it was the latter – the SG asked for leave to file a brief and to argue the case at oral argument. Both requests were granted.

The SG has filed a lengthy, complex and highly nuanced brief in this case, parsing various claims and theories under Section 230 in detail. The bottom line is that it is urging the Court to support the Gonzalez family and estate and overrule the Ninth Circuit:

Plaintiffs’ allegations regarding YouTube’s use of algorithms and related features to recommend ISIS content require a different analysis. That theory of ATA liability trains on YouTube’s own conduct and its own communications, over and above its failure to block or remove ISIS content from its site. Because that theory does not ask the court to treat YouTube as a publisher or speaker of content created and posted by others, Section 230 protection is not available.

In other words, in the eyes of the SG Gonzalez wins, Google loses.

The SG is careful to note that this does not mean that Google should be deemed an information content provider with respect to the videos themselves. In other words, the SG argues that Google is not liable for the ISIS postings – only that Section 230 does not shelter it from potential liability based on the fact that its algorithm recommended them.

All eyes will be on Justice Thomas during oral argument on February 21st. While several justices have expressed concerns over the broad immunity provided by the lower courts’ application of Section 230, Justice Thomas has been the most outspoken Justice on this issue. He expressed his views on Section 230 in Malwarebytes v. Enigma Software Group USA, a case where the Court denied review.

In Malwarebytes Justice Thomas agreed with the denial, but wrote an almost 3,000 word “Statement” criticizing much of the Section 230 jurisprudence for “adopting the too-common practice of reading extra immunity into statutes where it does not belong.” He criticized cases providing Section 230 immunity to websites that selected, edited and added commentary to third-party content, tailored third-party content to facilitate illegal human trafficking, and published third-party content on sites that had design defects lacking safety features. Importantly for this appeal he criticized websites that utilized recommendations, as Google does on Youtube.

There is little question where his vote will fall.

My prediction: Section 230 will not emerge from this appeal unscathed. The only question is the extent to which the Supreme Court will narrow its scope. Justice Thomas will write the opinion.

Update: The Supreme Court dodged the issue based on its holding in Twitter v. Taamneh. In that case, decided the same day as Gonzalez, the Court declined to impose secondary liability on tech companies for allegedly failing to prevent ISIS from using their platforms for recruiting, fundraising, and organizing. The Court ruled that internet platforms cannot be held secondarily liable under Section 2333 of the Anti-Terrorism Act based solely on broad allegations that they could have taken more aggressive action to prevent terrorists from using their services. This ruling applied to Gonzalez case as well, and therefore the Court did not address the Section 230 issues.

by Lee Gesmer | Jan 7, 2023 | Noncompete Agreements

There aren’t many issues in business law as divisive as non-compete agreements. Some people believe that non-competes are essential to protect trade secrets and confidential information. Critics argue that they suppress wages, reduce competition and keep innovative ideas from breaking into the market. In the eyes of many critics they are a contractual form of involuntary servitude. We’ve encountered many employees who were unaware that their employment agreements contained a non-compete clause until they tried to leave their job, or who were under the mistaken impression that noncompetes are legally unenforceable.

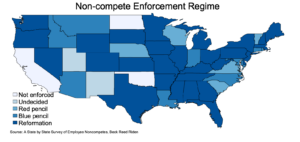

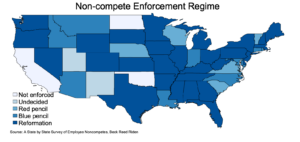

Despite this controversy, changes to noncompete law have been complicated by the fact that non-compete agreements are creatures of state law. Every state has its own body of non-compete law. Sometimes the law is based on statute, and sometimes it’s judge-made common law.

Among the states there is enormous variation. Some states, notably California, have laws that make non-competes unenforceable. In Massachusetts judges enforced non-competes under common law for decades until, in 2018, the state passed a law severely restricting them. In New York non-competes are enforceable, but there is no statute, just judge-made common law.

Non-compete agreements are so state specific that if a client asks us to advise on a non-compete subject to the laws of a state other than Massachusetts we have to consult a lawyer in that state who knows the intricacies of that state’s laws.

All of this may be about to change.

Federal Agency Proposals on Non-Compete Agreements

In 2016 the federal government entered the debate over non-compete agreements for the first time when the Obama administration issued reports critical of non-competes and suggesting policy changes. (2016 Treasury Report; 2016 White House Report).

This initiative was dormant during the four years of the Trump administration, but was revived in July 2021 when the Biden White House released an Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy “encouraging” the FTC to “exercise the FTC’s statutory rulemaking authority under the Federal Trade Commission Act to curtail the unfair use of non-compete clauses and other clauses or agreements that may unfairly limit worker mobility.”

The FTC’s Current Proposed Rule

The wheels of the law grind slowly but now – 18 months later – the FTC has proposed a rule that would ban all non-competes for both employees and independent contractors, as well as nondisclosure agreements that act as “de facto” non-competes. There are exceptions (most notably non-competes entered into as part of the sale of a business), but most non-compete agreements – including those currently in effect – would be prohibited.

The FTC’s “overview” of the proposed rule captures the “anti-non-compete” arguments:

About one in five American workers—approximately 30 million people—are bound by a non-compete clause and are thus restricted from pursuing better employment opportunities. A non-compete clause is a contractual term between an employer and a worker that blocks the worker from working for a competing employer, or starting a competing business, typically within a certain geographic area and period of time after the worker’s employment ends. Because non-compete clauses prevent workers from leaving jobs and decrease competition for workers, they lower wages for both workers who are subject to them as well as workers who are not. Non-compete clauses also prevent new businesses from forming, stifling entrepreneurship, and prevent novel innovation which would otherwise occur when workers are able to broadly share their ideas. The Federal Trade Commission proposes preventing employers from entering into non-compete clauses with workers and requiring employers to rescind existing non-compete clauses. The Commission estimates that the proposed rule would increase American workers’ earnings between $250 billion and $296 billion per year. The Commission is asking for the public’s opinion on its proposal to declare that non-compete clauses are an unfair method of competition, and on the possible alternatives to this rule that the Commission has proposed.

It’s not uncommon for federal law to preempt state law, and that would be the case under this rule – the rule would supersede any conflicting state law. In other words, the rule would render almost all state non-compete laws – statutory or judge-made – obsolete. Employers, regardless of size, would be required to notify employees that any existing noncompete clause has been rescinded.

If it became law this rule would be a sea change in noncompete law and, more broadly, employment law. Decades of established non-compete law would be wiped from the books.

Implications

The implications have many lawyers who work in the areas of non-compete agreements and employment law pinching themselves to make sure they’re not dreaming.

I’ll write in more detail about this proposed rule as the rulemaking process proceeds, but here are a few initial observations:

First, like many federal laws or agency rules the law is complex – it weighs in at over 1400 words. If it becomes effective its full implications will be understood through further explanation from the FTC and interpretation by the courts. The “de facto” provision alone – which would treat some nondisclosure agreements as non-competes – is ripe for litigation. In other words, there’s a lot to unpack here.

Second, should this rule become effective it can be challenged in court, and almost certainly will be. In fact, the sole Republican FTC Commissioner, Christine Wilson, has already issued a dissenting statement criticizing the proposed rule on substantive grounds and outlining the possible bases for challenging the FTC’s rulemaking authority for this proposed rule. The first of these is likely to be that the rule exceeds the FTC’s authority to regulate“unfair methods of competition.”

Third, federal agency rules are not statutes – they can be reversed by later rules, and in that respect they are somewhat impermanent. The implications of an “on-again/off-again” federal non-compete policy are harrowing to contemplate.

Fourth, what should you do while this rulemaking is pending? The answer is probably nothing – if you’re an employer that uses noncompetes it’s business as usual, along with “watchful waiting,” to borrow a medical term. Theres no reason to change your business practices until the proposed rule becomes effective. Worst case, any noncompetes you enter into during this period will be void. Of course you want to have a nondisclosure provision in your form of employment agreement, but you probably have that already, so it’s likely no change will be required.

If you’re a prospective employee and you’re evaluating a job offer that requires a noncompete, you should be on the defensive and negotiate terms. Again, this rule may never come to fruition, and your noncompete may be fully enforceable. Don’t assume that it won’t be.

Lastly, an essential element of rule-making is that the public gets to submit “comments” on the proposed rule, which – at least in theory – the FTC considers before finalizing the rule. However, in the world of federal agency rule-making, “comments” can include extensive legal and economic analyses and industry position papers. We can expect a flood of comments and a robust debate on this proposed rule, perhaps followed by public hearings. By the time the rule takes effect – if it ever does – it may be substantially different from what has been proposed.