by Lee Gesmer | Jul 30, 2013 | Corporate Law

Click here for direct access to a pdf of this document. This advisory was updated on August 1, 2013, to reference a FAQ issued by DOR on July 31, 2013.

[pdf file=”http://gesmer.com/media/pnc/6/media.386.pdf”]

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 22, 2013 | Copyright, What Were They Thinking

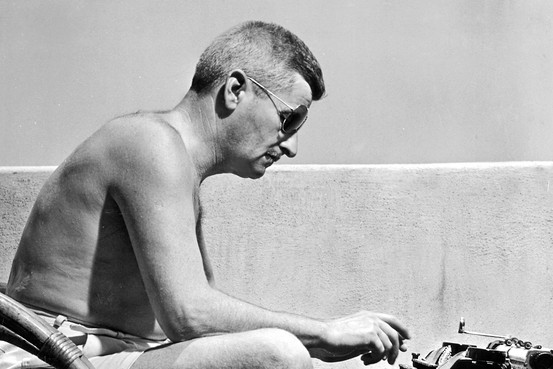

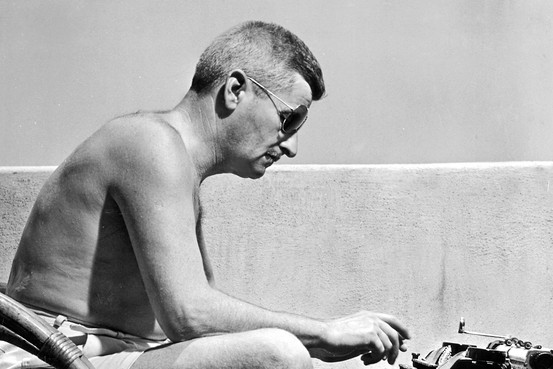

“It was as though she realised for the first time that you – everyone – must, or anyway may have to, pay for your past; the past is something like a promissory note with a trick clause in it which, as long as nothing goes wrong, can be manumitted in an orderly manner, but which fate or luck or chance, can foreclose on you without warning.” Requiem for a Nun, William Faulkner

__________________

For many years the Estate of James Joyce was infamous for its use of copyright law to restrict what many people considered fair uses of Joyce’s works. Now that most of Joyce’s works are in the public domain, it seems that the owner of William Faulkner’s copyrights, Faulkner Literary Rights LLC (“Faulkner”, is stepping up to take its place. But in the “Midnight in Paris” case you’ve gotta wonder: what the heck was Faulkner thinking?

Even many people who have never read a word of William Faulkner will recognize these famous lines: “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” These words are spoken by the fictional County attorney Gavin Stevens in Faulkner’s novel Requiem of a Nun.

The production of a Hollywood movie oftenrequires the producer to obtain many copyright permissions. However, when Woody Alan’s Midnight in Paris was released in 2011, one of the characters paraphrased these lines from Faulkner. When the protagonist, Gil (played by Owen Wilson) accuses his wife, Inez (played by Rachel McAdams) of having an affair she asks him where he got that idea. He responds that he got the idea from Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Salvador Dali, a response that Inez ridicules because they are all dead. In response, Gil quotes Faulkner: “The past is not dead. Actually, it’s not even past. You know who said that? Faulkner, and he was right. And I met him too. I ran into him at a dinner party.”

The producers of Midnight in Paris may have tried and been denied the right to use these words, or they may not have tried at all, concluding that the use was too minimal, and too transformative, to require a license. Regardless, after the movie appeared Faulkner sued Sony Pictures Classics Inc. in federal court in Mississippi alleging, among other things, copyright infringement. On July 18, 2013 the case was dismissed based on the fair use doctrine. Faulkner Literary Rights LLC v. Sony Pictures Classics Inc.

The federal judge who drew this case, Judge Michael P. Mills,* did his level best to address the Faulkner estate’s case with a straight face, and wrote an opinion that would do any college English major proud. However, he gave himself away when he commented, “how Hollywood’s flattering and artful use of literary allusion is a point of litigation, not celebration is beyond this court’s comprehension.”

*Judge Mills is a graduate of the University of Mississippi and has lived in Mississippi for more than 30 years, although there’s no reason to think he’s ever visited Yoknapatawpha County.

Predictably to everyone except Faulkner, Judge Mills found the movie’s use of the quote highly transformative, a key factor in determining whether a copy qualifies as fair use. The heart of the court’s decision is captured in this quote:

The speaker, time, place, and purpose of the quote in these two works are diametrically dissimilar. Here, a weighty and somber admonition in a serious piece of literature set in the Deep South has been lifted to present day Paris, where a disgruntled fiancé, Gil, uses the phrase to bolster his cited precedent (that of Hemingway and Fitzgerald) in a comedic domestic argument with Inez. Moreover, the assertion that the past is not dead also bears literal meaning in Gil’s life, in which he transports to the 1920’s during the year 2011. It should go without saying that this use is highly distinguishable from an attorney imploring someone to accept responsibility for her past, a past which, to some extent, inculpates her for the death of her child. Characters in both works use the quote for antithetical purposes of persuasion. On one hand is a serious attempt to save someone from the death penalty, and on the other is a fiancé trying to get a leg up in a fleeting domestic dispute. The use of these nine words in Midnight undoubtedly adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.

In addition to its claim of copyright infringement, Faulkner alleged  violation of the Lanham Act. Faulkner claimed that the film would “deceive or confuse viewers as to a perceived affiliation, connection or association between William Faulkner and his works on the one hand, and Sony, on the other hand.” The proposition that the use of this Faulkner quote in Woody Alan’s movie would confuse viewers as to a perceived affiliation between Faulkner and Sony is, if not an insult to the intelligence of Americans, certainly an insult to the New Yorker(ish) fans of Woody Alan. The judge denied this claim out of hand.

violation of the Lanham Act. Faulkner claimed that the film would “deceive or confuse viewers as to a perceived affiliation, connection or association between William Faulkner and his works on the one hand, and Sony, on the other hand.” The proposition that the use of this Faulkner quote in Woody Alan’s movie would confuse viewers as to a perceived affiliation between Faulkner and Sony is, if not an insult to the intelligence of Americans, certainly an insult to the New Yorker(ish) fans of Woody Alan. The judge denied this claim out of hand.

What was Faulkner thinking when it filed this case?

_________________________

Bonus content 1 – Letter in which William Faulkner quite his job with the U.S. Postal Service:

October, 1924

As long as I live under the capitalistic system, I expect to have my life influenced by the demands of moneyed people. But I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp.

This, sir, is my resignation.

(Signed by Faulkner)

Bonus content 2 – A couple of days after this post was published the Wall Street Journal published an extensive article on Faulkner’s attempts to capitalize on William Faulkner’s estate, including an unsuccessful attempt to sell Faulkner’s 1949 Nobel Prize medallion. The article discusses similar efforts by the estates of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Joyce and Nabokov.

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 12, 2013 | Copyright

Why did a Boston affiliate of ABC file suit a major copyright infringement action against Aereo in Boston, rather than ABC itself? Or another major broadcaster, such as CBS, NBC or Fox?

On May 15th, in a post titled “Does Second Circuit Decision Determine Copyright Legality of Aereo “Antenna-Farm” System Nationwide?”, I discussed the fact that Aereo had filed a preemptive suit in the Southern District of New York. The suit asked the federal district court to enjoin the major broadcasters (ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox) from filing what Aereo called “duplicative-follow-on suits” or “do-overs.” Aereo was attempting to prevent the broadcasters from following it around the country and filing a new copyright infringement lawsuit in each circuit in which Aereo launched its service. Aereo argued that the opinion of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in WNET v. Aereo, holding that Aereo’s retransmission of over-the-air broadcasts do not violate broadcaster copyrights, was binding nationwide on the plaintiffs in that case.

However, as I pointed out in May, even if that legal argument were to be successful, at best it would only be binding on the plaintiffs in that case. For example, while ABC was a plaintiff in New York and could, conceivably, be bound nationwide by the Second Circuit decision, Aereo could not stop a non–party, such as a local affiliate, from bringing suit in another district.

In fact, that is precisely the strategy the broadcasters have followed in Boston, the second market in which Aereo has released its service. The sole plaintiff in the Boston case is a local ABC affiliate station, WCVB–TV. The complaint emphasizes WCVB’s copyright rights in its original, local programming (Chronicle, CityLine, news and weather), shows in which WCVB, not ABC, owns the copyrights.

Now you know why a local affiliate sued Aereo in Boston.

(For the first post in a four-part series on the Aereo cases, click here).

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 12, 2013 | Antitrust

All antitrust cases are tried twice – once before the appeal, and once after the appeal. anon

__________________________

The district court decision in U.S. v. Apple presents about as clear a case of price fixing as one can imagine. Apple participated in a conspiracy with five of the “Big Six” publishers (an incestuous group based entirely in Manhattan) to raise prices for e-books above the $9.99 price charged by Amazon.

This was not subtle stuff—it was conduct worthy of the classic 19th century price fixers that led to enactment of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. Secret meetings among competitors to figure out a way to stop the hated price-cutter (Amazon), a White Knight that facilitates the conspiracy to foil the price-cutter (Apple), and an industry with its feet deeply planted in tradition (book publishing) under assault from a new technology (e-book publishing).

The only thing that makes this price-fixing conspiracy different from those in the 19th century is the massive email trail that the parties left, making the government’s courtroom proof that much easier. At least the classic price-fixers had the sense to keep up a pretense of secrecy, and not leave a trail of writings that would be their undoing in court.

Despite loud criticism of the district court decision from some quarters (see, for example, Guilty of Competition, WSJ, subsc.), it’s difficult to imagine that this decision will be overturned by the Second Circuit or (as the Journal wishfully dreams), the Supreme Court. Horizontal price fixing is per se illegal, and Apple acted as the ringmaster for the price fixing in this case. If there is one thing that is certain in antitrust law (an exceptionally difficult area of law with a very high reversal rate), there is no justification for price fixing. Amazon may have had a 90% market share of the e-book market. Amazon’s 9.99 e-book price may have been below the wholesale cost it paid to the book publishers. The book industry and authors may have been suffering economic harm from Amazon’s aggressive pricing. Amazon’s pricing, along with the growth in e-books, may have threatened to disrupt the book publishing industry in ways never before seen in that industry.

However, under antitrust law none of this matters: the Apple/publisher conspiracy to force book prices above the Amazon price of 9.99 was per se illegal, and no “justification” is relevant.

In light of this, a curious question arises: where were the lawyers? Apple has  a huge legal department, and surely some of the lawyers involved in this massive attempt to corral the “Big Six” book publishers and help them raise prices industry-wide had at least a rudimentary knowledge of antitrust law. Any lawyer who takes antitrust in law school, or studies the topic even casually, comes away remembering one thing: price fixing is per se illegal. The law tolerates no excuse.

a huge legal department, and surely some of the lawyers involved in this massive attempt to corral the “Big Six” book publishers and help them raise prices industry-wide had at least a rudimentary knowledge of antitrust law. Any lawyer who takes antitrust in law school, or studies the topic even casually, comes away remembering one thing: price fixing is per se illegal. The law tolerates no excuse.

Not surprisingly, there is no mention of legal advice Apple or any of the publishers received on the implications of their actions under antitrust law; after all, these communications would have been attorney-client privileged. It is possible that lawyers for Apple or the publishers were pulling their hair out warning their clients that they were taking terrible risks under the antitrust laws. It is possible that Apple and the publishers that joined in this conspiracy decided that the benefits of their plan outweighed the risks, although that is difficult to imagine. After all, given the large number of people involved, and the way the plan unfolded publicly, there was no chance that the plan could be kept “secret.” The result: a pre-trial settlement by all of the publishers and an embarrassing lawsuit for Apple (the full implications of which remain to be seen), were predictable.

And, business executives don’t often ignore their lawyers’s advice. One would think that attorney’s for one of the publishers would have warned it, and that the forewarned publisher would have mentioned this in one of its emails with Apple or the other publishers (which would not be privileged). However, in the 160 page decision, there is no hint of this.

So, the question remains unanswered, and puzzling: where were the lawyers?

This case may fall within the maxim that all antitrust cases are tried twice, but it seems unlikely. Perhaps, as some have argued, application of the per se doctrine in the context of this case (industry joint action to create a counterweight to a company with monopoly power) is bad economic policy.* But it seems unlikely that the courts will choose this case in which to deviate from over a century of antitrust doctrine.

*A counter-argument is that the Department of Justice under-reacted, and that it should have brought criminal charges under the antitrust laws, rather than merely civil charges.

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 9, 2013 | Contracts, Trade Secrets

A lot of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) provide that if one party gives the other a document and expects it to be treated as confidential, the document must be marked “confidential.” Or, if the confidential information is communicated orally, the party that wants to protect it must notify the receiving party in writing within a specified number of days. (“Hey, the stuff we told at our meeting on Monday relating to our fantastic new product idea? That’s all confidential under our NDA”).

This was the situation in Convolve, Inc. v. Compaq Computer, decided by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on July 1, 2013. The NDA at issue in that case provided that to trigger either party’s confidentiality obligations “the disclosed information must be: (1) marked as confidential at the time of disclosure; or (2) unmarked, but treated as confidential at the time of disclosure, and later designated confidential in a written memorandum summarizing and identifying the confidential information.”

Big mistake. People sign agreements like this and a year later they have completely forgotten that they need to follow them. Or, employees come and go, the NDA is buried away someplace, and new employees are blithely unaware that they need to follow the terms of the NDA.

That’s what happened to Convolve. It had trade secrets relating to hard disk drive technology. It disclosed the secrets at a meeting, but it failed to follow-up and designate it confidential under the NDA. Its argument that the parties knew the information was confidential (even though it wasn’t designated), went nowhere with the CAFC:

Convolve contends the district court erred when it found that Compaq failed to protect the confidentiality of certain information because it failed to designate it as such pursuant to its obligations under the NDAs. Convolve asserts that the parties understood that all of their mutual disclosures were confidential, notwithstanding the marking requirements in the NDAs. … Convolve … contends that the parties’ course of conduct did not require a follow-up letter. … The plain language of the NDA unambiguously requires that, for any oral or visual disclosures, Convolve was required to confirm in writing … that the information was confidential. … The intent of the parties, based on this language, is clear: for an oral or visual disclosure of information to be protected under the NDA, the disclosing party must provide a follow-up memorandum. … Convolve argues that, regardless of whether the confidentiality of the trade secrets was confirmed in writing, … the parties understood their mutual disclosures were confidential, notwithstanding the NDA strictures. … [However], the NDAs do not appear reasonably susceptible to the interpretation Convolve urges.

Don’t put provisions like this in your NDAs if you want to protect your trade secrets or confidential information. Include a provision that everything you give to your business partner is confidential, and keep your options open. If something isn’t confidential, no harm done. If you think it is and the recipient disagrees, let the recipient prove it in court, should that become necessary. Better overkill than underkill.

violation of the Lanham Act. Faulkner claimed that the film would “deceive or confuse viewers as to a perceived affiliation, connection or association between William Faulkner and his works on the one hand, and Sony, on the other hand.” The proposition that the use of this Faulkner quote in Woody Alan’s movie would confuse viewers as to a perceived affiliation between Faulkner and Sony is, if not an insult to the intelligence of Americans, certainly an insult to the New Yorker(ish) fans of Woody Alan. The judge denied this claim out of hand.

violation of the Lanham Act. Faulkner claimed that the film would “deceive or confuse viewers as to a perceived affiliation, connection or association between William Faulkner and his works on the one hand, and Sony, on the other hand.” The proposition that the use of this Faulkner quote in Woody Alan’s movie would confuse viewers as to a perceived affiliation between Faulkner and Sony is, if not an insult to the intelligence of Americans, certainly an insult to the New Yorker(ish) fans of Woody Alan. The judge denied this claim out of hand.

a huge legal department, and surely some of the lawyers involved in this massive attempt to corral the “Big Six” book publishers and help them raise prices industry-wide had at least a rudimentary knowledge of antitrust law. Any lawyer who takes antitrust in law school, or studies the topic even casually, comes away remembering one thing: price fixing is per se illegal. The law tolerates no excuse.

a huge legal department, and surely some of the lawyers involved in this massive attempt to corral the “Big Six” book publishers and help them raise prices industry-wide had at least a rudimentary knowledge of antitrust law. Any lawyer who takes antitrust in law school, or studies the topic even casually, comes away remembering one thing: price fixing is per se illegal. The law tolerates no excuse.