by Lee Gesmer | Apr 27, 2022 | Copyright

If you own or manage a website you may be familiar with the process of “photo embedding” or “inline linking” an image or video on your site. Rather than hosting the image file on your own server you retrieve the image from another Internet site and embed the content as part of your webpage’s overall display. Users can’t tell the difference, but as a technical (and legal) matter you never “copy” the image to your server.

This practice is common, and has been performed millions of times on millions of sites. You have no legal concerns since you’re just channeling the image from another site. No worries, right?

Not so fast. This is actually a hotly disputed legal issue in the world of digital copyright.

For many years there actually were no worries. Way back in 2007 the Ninth Circuit created what has come to be called the “server test” in Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc. This gave unauthorized embedding a legal green light so long as the image resided on another server. In copyright lingo the embedding site does not host any “material objects … in which a work is fixed … and from which the work can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated” and thus does not communicate a copy. 17 U.S.C. § 101.

However, in addition to the right of reproduction the Copyright Act gives the owner of a work the right of public display – copyright owners have the exclusive right to “transmit or otherwise communicate… a display of the work… to the public, by means of any device or process.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. The Ninth Circuit used similar reasoning to hold that an image is not displayed when the embedding site’s computer does not store the photographic images.

For many years the “server test” has been shaky but accepted law. A few courts around the country suggested that the Ninth Circuit’s holding that unauthorized embedding didn’t constitute public display was questionable, but there were no clear rulings on this issue.

However, in the recent decision in McGucken v. Newsweek LLC (S.D. N.Y. March 21, 2022) a federal district court in the southern district of New York (the “SDNY”) outright rejected this rule in a case in which Newsweek embedded a photographer’s Instagram post in an online news article without his permission. The court focused on the right of display and concluded that –

After all, the Copyright Act defines “display” as “to show a copy of” a work, 17 U.S.C. § 101, and not “to make and then show a copy of the copyrighted work.” . . . The Ninth Circuit’s approach, under which no display is possible unless the alleged infringer has also stored a copy of the work on the infringer’s computer, would seem to make the display right merely a subset of the reproduction right. . . . The Copyright Act makes clear, however, that to “show a copy” is to display it. . . . Therefore, the Court finds that Defendant did in fact display Plaintiff’s Photograph when it embedded the Photograph in the Article.

In fact, this is the second time an SDNY court has reached this conclusion. In Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, LLC (2018) the district court held that an embedded tweet violated the photographer-plaintiff’s right of public display: “the plain language of the Copyright Act . . . provides no basis for a rule that allows the physical location or possession of an image to determine who may or may not have ‘displayed’ a work within the meaning of the Copyright Act.” (See my earlier post, Is In-Line Linking Illegal Now?).

However, in Goldman the Second Circuit denied interlocutory review and the case settled before any appeal. Hence, the issue didn’t reach the Second Circuit in that case.

The split between the Ninth Circuit and the trial courts in the southern district of New York leaves website owners with a difficult decision – do they assume that Ninth Circuit law is controlling, and therefore continue to embed images? Clearly, for trial judges in SDNY the answer is “no” – these courts, at least, have made clear that they view this practice to be a violation of the right of public display. And, since a copyright plaintiff can often engage in “forum shopping” and file a copyright suit in that district the only safe conclusion is that this practice should be avoided nationwide, at least until one of the southern district cases reaches the Second Circuit on appeal and the split between the SDNY and the Ninth Circuit is resolved. If the Second Circuit creates a circuit split with the Ninth Circuit at the appellate level, the issue would be ripe for Supreme Court review.

There is another dimension to this issue that bears mentioning: the copyright issues are intertwined with complex terms, conditions and technical measures imposed by photo hosting services.

The poster child for this is Instagram. Instagram is the most popular source of images for embedded images, and it facilitates embedding by providing an embedding API. Late last year Instagram introduced a new feature allowing copyright owners to disable the embedding feature for photos they post. Before that, Instagram posters had to elect to use a private account to block unwanted embedding.

Instagram’s change to its embedding policy may reduce the likelihood of future copyright cases on this issue, but not by much. Many Instagram posters are unlikely to become aware of or implement this feature. Other social media and photo hosting sites, such as Twitter, Facebook and Flickr, have not followed Instagram’s policy. And, of course, there are millions of hobbyist and small-business sites that will not bother to block photo embedding, making it likely that this issue will continue to be the subject of litigation.

Stay tuned.

McGucken v. Newsweek LLC (S.D. N.Y. March 21, 2022)

Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, LLC 302 F.Supp.3d 585 (S.D.N.Y 2018)

by Lee Gesmer | Mar 18, 2022 | Copyright

The scope of copyright law is vast – it protects traditional art forms such as books, music, photos and paintings, but also covers more exotic forms of expression, such as computer software, choreography, literary and movie characters (Batman, James Bond) and even useful objects (product and clothing designs).

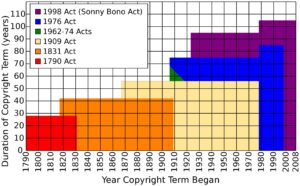

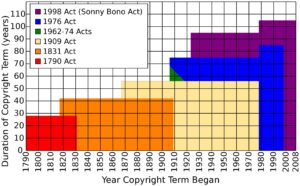

However, it can be difficult to determine whether a particular work is protected by copyright due to the passage of time or failure to comply with once-essential “formalities.” Many people know that under current copyright law a copyright lasts for the “life of the author plus 70 years” or, if the work was created by an employee and is a “work for hire” 95 years from publication. Unfortunately, for older works it’s not that simple – duration is complicated by the fact that as Congress has increased the term of copyright protection for new works it has had to struggle with readjusting the term for older works, leading to a series of arcane retroactive rules that control the copyright status of what have come to be known as “orphan works.”

THE FOUR COPYRIGHT ERAS

There are four major time periods – four “eras” – that need to be considered when determining whether a work is protected by copyright or has entered the public domain.

THE FIRST ERA: Pre-1923

Although all works published before 1923 are in the public domain today, historical context is helpful to understanding copyright duration. To find that we have to look back more than a century, to the Copyright Act of 1909. Relatively speaking, copyright protection was short then. Between 1909 and 1923 works registered with the Copyright Office were protected for 28 years from publication.

At the end of the 28 year term the owner had the option to renew the copyright. If the owner renewed protection was extended for a second consecutive 28 year term, known as the “renewal term”. Thus, with renewal works could be protected for a total of 56 years. Congress has not extended the copyright for pre-1923 works, and therefore they are in the public domain whether their copyright lasted 28 or 56 years.

THE SECOND ERA: 1923 – 1963

In 1996 Congress passed the Copyright Term Extension Act, which became effective in 1998. This law increased the copyright term for works published after that date. At the same time it reset the term for works published between 1923 and 1963. Works whose registration was still in their first term or had been renewed (by then the renewal term had been extended to 47 years, extending the full two terms to 75 years and making it possible for works published in 1923 to remain protected in 1998) were given a new life – 95 years from publication. This created a 20 year “gap” during which works that would have entered the public domain in 1998 were protected for an additional 20 years. However, the 20 year period has lapsed, and these works have been falling into the public domain annually each year since 2019. Works published in 1923 entered the public domain on January 1, 2019, works published in 1924 in 2020, and so on. To date works published in 1923, 1924, 1925 and 1926 have entered the public domain. This process will continue until 2057 when, finally, works published in 1961 will enter the public domain.

THE THIRD ERA: 1964 – 1977

Expansion of U.S. copyright law (assuming authors create their works 35 years before their death)

The third major era covers the years from 1964-1977. Once again, when Congress changed the rules in 1998 it changed the term for these works retroactively. Works published during these years are protected for 95 years, and there is no registration or renewal requirement. Thus, a work published in 1964 will fall out of copyright on January 1, 2059, works published in 1965 in 2060, and continuing until 2072, when the final cohort – 1977 works – will lose protection.

THE FOURTH ERA: 1978 – PRESENT

Works published after January 1, 1978 are protected for the life of the author + 70 years or, in the case of works for hire, 95 years. Works for hire – works created by employees – are a large share of copyright-protected works. For example, all Hollywood movies are works for hire, and therefore a movie released in 2022 will be protected for 95 years, until 2117.

The “life + 70 years” term has the potential for even longer duration for works that are not works for hire – the 30 year old author of a book published today might live another 60 years, to age 90. That 60 years, plus 70 years following the author’s death, could result in the work being protected for 130 years, until 2152. This will be true even if the author sells or assigns the work – the life of the copyright continues to run based on the life of the author, even after the author no longer owns the copyright.

ORPHAN WORKS – DETERMINING WHETHER A WORK IS PROTECTED CAN BE DIFFICULT

As this trip through history shows there has been a slow but continuous expansion of copyright duration from 28 years in 1909 to potentially well over 100 years today.

However, the fact that Congress has enacted rules retroactively can make it difficult to determine whether many older works are still under copyright. Owners can’t be identified or located and registration records are imperfect – it can be difficult to determine whether the author complied with mandatory registration and renewal requirements, or even who owns the copyright today. A copyright may have been lost based on publication without a proper copyright notice (notice was mandatory before 1977). The Duke Law School Center for the Study of the Public Domain reports that most older works are “orphan works,” where the copyright owner cannot be found at all.

Nevertheless, potential users of orphan works cannot blame inefficiencies in the system – the obligation to perform thorough research and “clear” a work rests with those wishing to use these works. Failure to do so could result in an expensive claim of copyright infringement.

Caveat lector: Copyright duration is an exceedingly complex and technical topic. This article should be viewed as a high-level summary of copyright duration for U.S. law. There are legal requirements beyond the rules described here.

by Lee Gesmer | Dec 25, 2021 | Antitrust

When I was a newbie lawyer just out of law school I worked at a Washington D.C. “BigLaw” firm that concentrated on antitrust law. We represented a client in a criminal antitrust case that involved bid rigging in the highway and airport paving industry. It turns out that bid rigging was rampant in the U.S. southeast, leading to many indictments, guilty pleas and convictions.You can read about it in this 1982 court decision.

What is bid rigging? Typically a state highway or transportation agency would issue a request for bids on a highway paving project. Potential bidders would either ask other contractors not to bid or arrange for them to enter a high bid. Although the winning bidder would have the lowest bid, it would be higher than it might have been had all contractors competed for the job.

The bid rigging case my firm handled was a big one – in fact, when our client eventually pled guilty it paid the largest criminal antitrust penalty in U.S. history to date.

However, before our client pled guilty my firm prepared to defend the case at trial, and the partners gave me a research assignment: find cases that will allow us to argue that bid rigging is not “per se” illegal.

For readers without a background in antitrust law here’s context.

Per Se vs. Rule of Reason

When it comes to anticompetitive conduct that falls under the Sherman Act there are two broad doctrines – “per se” illegality and the “rule of reason.” If the conduct in question falls under the per se rule the act constitutes an unreasonable restraint of trade, and it’s not necessary to consider motive or the economic effects. Under the per se rule an offender can’t justify its conduct by arguing (for example) that it had no anticompetitive effect. The classic example of this is price fixing – if a judge or jury concludes that two or more competitors got together and agreed to raise their prices they are guilty. Period and end of case.

By contrast, under the “rule of reason” a defendant can argue that although it may have engaged in conduct that is potentially anti-competitive, the pro-competitive effects outweighed the anticompetitive effects, and therefore the antitrust laws were not violated.

The judge decides whether a case is governed by the per se rule or the rule of reason. Therefore, antitrust defendants will often argue that the rule of reason should govern their case, and this was the rationale behind my assignment. The BigLaw partners running my case wanted to argue that our client’s bid rigging should be judged under the rule of reason.

It was apparent to the lawyers at my firm (at least the associates working with me) that this was a horizontal price fixing conspiracy, and therefore illegal “per se.” In fact, there were cases that held just that. “A conspiracy to submit collusive, non-competitive, rigged bids is a per se violation of the statute” United States v. Brighton Bldg. & Maintenance Co. (7th Circuit 1979). (link)

No surprise – my research found nothing to the contrary. I spent days in the library reading antitrust cases, hoping to find even a few words that might give us a toehold to argue that our client’s bid-rigging conduct should be judged under the rule of reason. I returned to the partners empty handed.

Is Wage-Fixing Judged Under the Rule of Reason or the Per Se Rule?

What brings this to mind today? – A federal court decision holding that wage-fixing is a per se violation. The case, United States v. Jindal, is the first criminal wage-fixing case brought by the Department of Justice. The federal indictment was returned in December 2020, and the decision that caught my attention was filed in December 2021.

The facts are straightforward – two individuals that owned physical therapy companies agreed to lower the pay rates for physical therapists and PT assistants. They were discovered and the Department of Justice (DOJ) Antitrust Division brought a criminal antitrust case against them.

Although the Jindal case was the first criminal indictment for wage-fixing a second case was filed in March 2021. (United States v. Hee) It’s clear that the labor markets are, for the first time, the focus of the criminal arm of the Antitrust Division.

This comes with plenty of advance notice. In 2016 the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) warned that wage-fixing agreements would be prosecuted criminally. President Biden’s July 2021 Executive Order focused on antitrust enforcement in labor markets. In early December the new Assistant Attorney General in charge of the DOJ Antitrust Division noted that many of the economic problems faced by workers have their “roots in collusion and unfair practices in the labor markets,” and warned that the DOJ Antitrust Division will be working closely with the FTC on issues relating to competition in the labor market. (link)

When I read the court’s November 2021 decision in Jindal I saw – shades of my long-ago bid rigging research! – that the defendants argued that wage-fixing is not per se illegal but should be judged under the rule of reason. Likely, a junior associate on the case was sent to the law books to find a precedent that might move wage-fixing from “per se” to “rule of reason.”

No such luck.

Jindal’s Arguments for Rule of Reason Strike Out

First, the defendants argued that wage-fixing is not the same as price-fixing and therefore does not constitute a per se violation. The court rejected this argument, noting that courts have held that a price-fixing conspiracy can pertain to services and price-fixing conspiracies among buyers (in this case employers who buy the services of employees), not just sellers.

Second, the defendants argued that the charges were insufficient because they failed to allege that the defendants had agreed to fix prices paid by consumers. The court rejected this argument, observing that it is well established that the Sherman Act “does not confine its protection to consumers,” but also protects employees.

Third, the defendants argued that courts lacked sufficient experience with wage-fixing to justify classifying it as a per se violation. The court rejected this argument – “The lack of criminal judicial decisions only indicates Defendants’ unlucky status as the first two individuals that the Government has prosecuted for this type of conduct.”

Bottom line: pending appeal and reversal, wage-fixing is a type of price-fixing—and price-fixing is the quintessential per se violation of the Sherman Act. Given the evidence in the case (inculpatory text messages) it looks like Mr. Jindal and his co-defendant should be getting their affairs in order in advance of a prison term.

DOJ Focuses on “No-Poach” Agreements

The broader takeaway for business executives is that while historically the DOJ treated no-poach agreements as civil antitrust violations, criminal prosecutions can lead to felony indictments and prison time. They also need to be aware that the DOJ Antitrust Division is looking beyond just wage-fixing – it has an eye out for “employee allocation agreements” – commonly referred to as “no-poach” or “no-hire” agreements. Under these agreements two or more employers agree that “I won’t hire your employees if you’ll agree you won’t hire mine.” The Antitrust Division is likely to argue that these agreements also are a per se antitrust violation. The DOJ filed an indictment against Surgical Care Affiliates LLC in January 2021 alleging an illegal no-poaching/no-hire agreement (link), and a second no-poach case against aerospace executives as recently as December 16, 2021, while I was writing this post. (link)

Oh, and by the way the associates in the firms defending the no-poach indictments better head for the library and start looking for cases that will persuade the judges that no-poach/no-hire agreements should be judged under the rule of reason.

Perhaps they’ll have better luck than I did.

(To read a 2012 post discussing no-poach/no-hire civil cases (not to be confused with the criminal indictments discussed above) see Repeat After Me: Competitors Cannot Agree Not to Hire Each Others Employees.)

Update: The defendants were acquitted in both cases following jury trials.

by Lee Gesmer | Nov 9, 2021 | General

Many people who’ve lived with the traditional rules of intellectual property during their professional lives are struggling with non-fungible tokens, or “NFTs”. I’m one, and it’s a bit of an existential crisis for us. My advice – relax and repeat after me: “this has nothing to do with copyright law.”

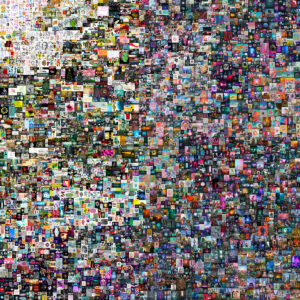

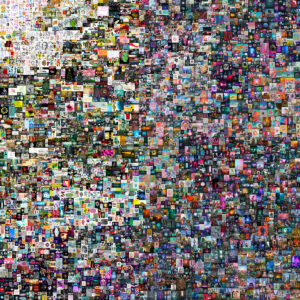

The existence of NFTs came to the attention of many people after Christie’s sold Beeple’s Everydays: the First 5000 Days – a collage of 5000 digital art images – for $69 million in early 2021. One of the 5000 images is at the top of this post. The purchaser was Vignesh Sundaresan, and to be precise, Sundaresan purchased this NFT in exchange for $69 million worth of Ether cryptocurrency.

What, I asked when I first heard this, did the buyer receive in exchange? I assumed the buyer received copyright title in the artwork. Or perhaps a license to the work. This was a copyright transaction involving digital art, right? Old wine in new bottles.

Wrong!

Although the subject matter of the Beeple NFT appeared to fall in the realm of copyright law – digital artwork – Mr. Sundaresan received none of these things, nor anything else that one would associate with copyright law.

Warning, blockchain jargon ahead: Mr. Sundaresan received a unique (hence “non-fungible”) crypto “token” – not to be confused with non-unique (hence “fungible”) cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum that can be traded on a blockchain. His purchase of this NFT was subject to a “smart contract” that you can read here (2,000+ lines of code, good luck). The token is managed (recorded, bought/sold) on a public blockchain, a decentralized, peer-to-peer network-based digital ledger system that tracks the ownership of the NFT. The token contains a link to a location on the Internet that holds a copy of the digital artwork, but there was no transfer of ownership of the artwork. Christie’s terms of sale made this clear to potential purchasers.

Beeple’s Everydays: the First 5000 Days

Let me stop now and note that, based on my reading on the subject, there’s a lot of confusion around NFTs, even among the Internet 3.0 cognoscenti. A photo or musical work created today is under copyright, and the owner (often the author, particularly in the world of NFTs) can control reproduction and public display/performance. In the world of traditional copyright transactions a buyer owns the physical copy s/he purchases. If there’s only one copy, or a limited series, the original may increase in value – this is why people invest in art.

By contrast the buyer of an NFT rarely (if ever) acquires ownership of the art work. And here we see the copyright conundrum – historically, no knowledgeable art investor would spend a large sum of money to buy a piece of digital art to which they didn’t own the copyright or a physical copy, and which could be reproduced and downloaded off the Internet with the right-click of a mouse.

This is the “legal” aspect of NFTs that leaves intellectual property lawyers perplexed – in many instances the seller of the NFT makes no promises, other than not to resell the specific NFT purchased by the buyer. The buyer owns nothing more than a fragment of code that exists on a blockchain, and a link to a website that holds an authentic copy (one hopes) of the artwork.

The point is this: in the world of NFTs – which typically involve artwork, video and music – purchasers of NFTs do not obtain any intellectual property ownership in the work associated with the NFT unless it is explicitly transferred. In the case of Beeple’s artwork, the buyer didn’t purchase the artwork and he didn’t purchase the copyrights – the buyer purchased the token, and the right to hold or resell it. The images in Beeple’s $69 million collage are all freely available on his website.

Now, lawyers, wake up! There’s good news for you. NFTs may be subject to “smart contracts.” What is a smart contract? It’s a computer program executed in the blockchain by algorithmic code when given certain data. You can see the Beeple contract linked above (the MakersTokenV2 standard), and another example here (the ERC721 standard). If you have the courage to click through you’ll see that these so-called “contracts” look nothing like traditional contracts – they are computer code.

However, with smart contracts traditional legal principles have infiltrated the world of NFTs – at least to the extent that a court can “translate” and enforce a code-based contract. The buyer and seller of the NFT can agree to copyright-like rights, either on the blockchain or even in a traditional “off-blockchain” natural language contract. They could also agree, for example, that if the token is resold a percentage of the resale price would be paid to the NFT creator, or some other third party (perhaps a charity). The smart contract would cause this to occur automatically and the designated recipient would receive payment in crypto currency without any human intervention.

So, to return to my original point – at first this is all a bit mind boggling to people steeped in traditional copyright law, but not so much if you understand that NFTs often involve works that could be the subject of traditional copyright transactions, but aren’t.

If you’ve been paying attention and think you’ve understood everything I’ve said, you may still feel confused. Don’t feel badly, almost everyone else is too. If you’d like to read further on this topic I recommend Deconstructing that $69million NFT (explaining what an NFT is, in technical detail) and the October 26, 2020 episode of the 4PC Podcast, which explains some of the legal issues involved with smart contracts.

If you still aren’t sure what an NFT is, or why people are willing to pay huge sums of money for them, I’ll leave you with copyright lawyer Rebecca Tushnet’s explanation. When asked to explain the value of a NFT she responded –

The value is the ability to say that you own the NFT. Like blockchain currency, it is worth whatever humanity collectively or individually decides it’s worth. It is a melding of Oscar Wilde and Andy Warhol, art for art’s sake and commerce for commerce’s sake.

by Lee Gesmer | Oct 13, 2021 | Noncompete Agreements

When Massachusetts passed its complex and restrictive noncompete law in 2018 (the “Massachusetts Noncompete Act” or the “Act”) it was predictable that the use of noncompete agreements in the state would decline. See A New Era In Massachusetts Noncompete Law. And, in fact, until now there have been no reported cases that involve the Act. Anecdotally, with few exceptions employers have stopped asking employees to enter into noncompete agreements. It’s just too darn complicated.

As I summarized in my 2108 post, the Massachusetts Noncompete Act created eight requirements for a noncompetition agreement to be legally binding. Of these the most challenging (for employers and the lawyers who advise them) is the requirement that the agreement provide the employee with garden leave “or other mutually-agreed upon consideration . . . specified in the noncompetition agreement.”

“Garden leave” is a term used to describe when an employee leaving a job is required to stay away from work for a period of time while continuing to be paid. As I described in 2018 in describing the Massachusetts Noncompete Act, garden leave occurs when an employer is required “to continue paying the employee, during the restricted period on a pro rata basis, no less than 50% of the employee’s annualized base salary, thereby financially enabling the employee to putter around in her ‘garden’ during the restricted period.” In other words, a one year noncompete would require the employer to pay the employee 50% of her base salary during the year.

Garden leave can be expensive for employers. However, the law contains a loophole – it allows the employer and employee to avoid garden leave by agreeing on “other mutually-agreed upon consideration.”

What constitutes “other consideration”? Does it have to be reasonable? Could an employer buy its way out of garden leave if the employer and employee agreed that the consideration could be one dollar? Could they agree that the very job offer itself is the mutually-agreed upon consideration?

Now a decision by Judge Timothy Hillman in the Massachusetts federal district court is the first reported case to apply the Massachusetts Noncompete Law. Because it is the first case in three years, it has received a good deal of attention in the legal community – however, I see it as little more than a nothingburger, beyond being a warning to employers not to ignore the Act.

In the case – KPM Analytics Corp. v. Blue Sun Scientific, LLC – Philip Ossowski signed a noncompete with KPM in 2019, after the new law took effect. However, Ossowski’s agreement did not state that Ossowski had the right to consult with counsel prior to signing (one of the eight requirements). And, it did not contain a garden leave clause or an agreed-upon consideration that would have allowed the employer to avoid garden leave payments. Hence, the court concluded that the agreement was unenforceable by KPM.

What’s the takeaway from this case?

Well, for starters any other outcome would have been surprising. The noncompete agreement violated the “consult with counsel” requirement, and it made no mention of garden leave at all. Therefore it failed two of the eight requirements. It seems that some Massachusetts lawyers have read the decision as holding that employment alone may not provide consideration for garden leave, but to me that seems self-evident, since it would largely obliterate the garden leave requirement. In any event, Judge Hillman does not address this theory or discuss it in his opinion.

However, Massachusetts lawyers are starved for court guidance on this law – after all it’s been three years since the law took effect. The only other case to touch on garden leave in the last three years is Nuvasive, Inc. v. Day (D. Mass. May 29, 2019), which involved a noncompete that had been entered into before the effective date of the Act. The Act does not apply to noncompetes entered into prior to its enactment.

In Nuavsive Massachusetts federal district court Judge Caspar suggested that had the new law applied and garden leave required, “compensation … received from the Company (including for example monetary compensation, Company goodwill, confidential information, restricted stock units and/or specialized training)” might have satisfied the option for “other mutually-agreed upon consideration.” However, given that the law did not apply in that case this was little more than dicta. And, she provided no discussion or rationale for such a conclusion.

The bottom line is that after KPM Analytics and Nuvasive, and three years after the law took effect, we still have no guidance from the legislature or the state courts as to how an employer and employee can agree on consideration that will stand in lieu of garden leave, without the risk that the employee will argue that the consideration was inadequate and therefore the noncompete is unenforceable.

I ended my 2018 post with the comment that “lawyers will struggle to explain all of this to bewildered clients, both employers and employees, for years to come.” Three years later, nothing has changed.