by Lee Gesmer | Aug 13, 2013 | Copyright

“The phone, the laptop and the tablet have advanced so dramatically. Television has been drastically left behind.” – Tom Rogers, CEO of TiVo, Inc., Wall Street Journal, July 30, 2013

_________________

First music, then books, now television. Music and book publishers have suffered well-publicized headwinds (some would say hurricane gales) at the hands of the Internet economy, and now 2013 is the year the TV and cable industries are beginning to face comparable technology-driven disruptive technologies.

Technical advances now allow people who live in New York, Boston or Atlanta to use Aereo to watch inexpensive over-the-air television on Internet-enabled devices (potentially freeing them from more expensive cable fees), and subscribers to Dish satellite TV to watch primetime network TV ad free

The broadcasters are fighting these developments in the marketplace and the courts, and the court actions have sent sparks flying in the world of copyright law.

I’ve written about the broadcasters’ ongoing legal efforts to shut down Aereo, However, the Ninth Circuit’s July 24, 2013 decision in Fox v. Dish Network adds another dimension to the TV industry’s copyright battles.*

*An important caveat in both cases is that the appellate courts were reviewing preliminary injunction decisions by district courts under a deferential standard of review. There is no certainty that the Second and Ninth Circuits will reach the same conclusion on an appeal of a final judgment in these cases.

Here are the facts in Dish.

Dish records the primetime programming of the four major network TV broadcasters – ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox. It manually inserts electronic bookmarks to mark the beginnings and ends of commercial breaks. Dish then downloads the programming to the hard drives in the set-top DVR boxes of subscribers who have pressed the button that “enables” this service.

These subscribers now have a box-top recording of the previous eight days of primetime programming, including ads. However, when they watch a show and the system encounters an electronic bookmark marking an ad the service skips to the next bookmark, “hopping” over the ads. Voilà! Dish subscribers have advertisement-free TV, “the feature viewers have been waiting for since the beginning of television.” Dish has given this ad-skipping service the name “AutoHop.”*

*The district court record suggests that an important motivation for Dish to create AutoHop may have been to compete with Internet-based programming from services such as Hulu and Hulu Plus.

Hopper Logo

If Aereo’s service – which feeds over-the-air TV programming to computers, tablets and smart-phones (ads and all) infuriated the network broadcasters, the Dish ad-skipping service – “which could destabilize the entire television eco-system” according to Moody’s – has left broadcast TV executives apoplectic. Fox filed suit for copyright infringement in California, but the district court denied Fox’s motion for a preliminary injunction. In a nightmare scenario following the networks’ thus-far unsuccessful battle with Aereo in the Second Circuit, the Ninth Circuit upheld the district court, relying in significant part on the Second Circuit’s controversial Cablevision decision, the case that was central to the broadcasters’ loss in Aereo.

Based on Cablevision, the Ninth Circuit held that because Dish’s AutoHop system creates copies only in response to the customer command enabling the service, the district court did not err in concluding that Dish is not engaged in direct infringement. Even though Dish provides the service, the customer, not Dish, is “the most significant and important cause of the copy.”

In Cablevision the Second Circuit asked “whether one’s contribution to the creation of an infringing copy may be so great that it warrants holding that party directly liable for the infringement, even though another party has actually made the copy.” However, the Second Circuit never identified that point in Cablevision, and although Fox argued that Dish, as an active participant in the activity of copying, had crossed that line, neither did the Ninth Circuit in Fox v. Dish.

If Dish is not the “direct” infringer (since the subscribers, not Dish engage in the “volitional conduct” that “makes” the copies), isn’t Dish liable under the theory of secondary liability?* After all, Dish puts the DVR devices in the hands of their subscribers, ready to use (with no options or vatiations), and shows them how to push the button that feeds the copies to them.

* One form of secondary liability under copyright law is to intentionally induce or encourage direct infringement. This theory of liability was not asserted in either Cablevision or Aereo. In Cablevision, the cable company “expressly disavowed” secondary liability as a theory of liability.

In response to this argument Dish fell back on the Supreme Court’s famous 1984 decision in Sony v. Universal (better known as the “Betamax case)”, and argued that copying by subscribers was fair use under that case.* However, the most important factor in fair use analysis is the harm to the market value of the copyrighted work, and in this case (unlike Sony) AutoHop clearly has an impact on the value of Fox’s TV shows, since they are supported by advertising revenues which are likely to shrink if people are skipping Fox’s paid advertising.

* Although there was evidence in Sony that 25% of Betamax users fast-forwarded though commercials, the Supreme Court in Sony never squarely decided whether commercial-skipping was fair use (as compared with time-shifting, which the Supreme Court held was fair use).

The Ninth Circuit attempted to side-step this argument by Fox by noting that Fox does not own the copyright to the ads, only the programming. Therefore, the Ninth Circuit concluded, “any analysis of the market harm should exclude consideration of AutoHop because ad-skipping does not implicate Fox’s copyright interests.” However, this conclusion seems to ignore the fact that Dish subscribers are copying Fox’s programming as well as its advertising, and therefore Fox’s copyright interests are implicated. Perhaps a copyright suit by an advertiser would have a better chance of establishing copyright infringement before the Ninth Circuit, and I suspect that Fox (or one of the other broadcasters) is considering the pros and cons of this strategy.

On August 7th Fox filed an impassioned Petition for Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc, pointing out a number of flaws in the Ninth Circuit panel’s reasoning and legal analysis. The Ninth Circuit is more amenable to en banc review than the Second Circuit (where en banc review is rare, and where it was denied in Aereo), and therefore Fox’s quest for a preliminary injunction is not necessarily over in the Ninth Circuit. And, if the panel decision is held to be the law in the Ninth Circuit after final judgment, the issues are so important that the case should be a good candidate for Supreme Court review.

It’s also worth keeping in mind the fact that Dish, like Aereo, is playing with fire. If Dish is found to have infringed Fox’s copyrights after final judgment in district court or on appeal, the damages could be significant, given the large number of copyrighted shows at issue and the potential for statutory damages of as much as $150,000 per infringement.*

*The district court and the Ninth Circuit suggested that Dish may be liable for copies it made for “quality control,” but that seems to be little more than a monetary footnote in the context of this case. And, it appears that Dish has stopped this practice. In addition, Fox has asserted a breach of contract claim against Dish. Based on the Ninth Circuit decision, this may turn out to be a better claim for Dish than its claim of copyright infringement.

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 8, 2013 | General

“The thing to fear is not the law, but the judge.” – Russian Proverb

_____________________________

Viacom has filed its opening brief in its second appeal in Viacom v. Youtube. This long-running copyright case is establishing important precedents in the interpretation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).*

*See this link for my most recent post on this long-runing case.

In its current appeal Viacom argues that the trial court judge erred in granting Youtube summary judgment following remand from the Second Circuit’s 2012 decision in this case.

The appeal raises many difficult and important issues in applying the DMCA, and it remains to be seen whether the Second Circuit will add clarity or confusion to this complex law. However, one element of Viacom’s argument jumps out instantly. Viacom’s brief includes a section titled “This Court Should Exercise Its Discretion To Remand The Case To A Different District Court Judge.” The text of the argument in support of this request, in its entirety, is as follows:

Given the protracted nature of this litigation (the case is now well into its seventh year) and the evident firmness of the district court’s erroneous views regarding the DMCA, this Court should exercise its discretion to remand the case to a different judge “to preserve the appearance of justice.” E.g., United States v. Robin, 553 F.2d 8, 10 (2d Cir. 1977). Reassignment would “not imply any personal criticism of the . . . judge,” nor would it “create disproportionate waste or duplication of effort,” given that the case has yet to go to trial. Scott v. Perkins, 150 F. App’x 30, 34 (2d Cir. 2005).

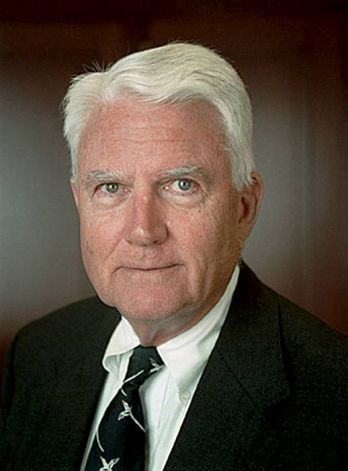

Well, that takes chutzpah! If the case is remanded to the district court for further proceedings and the case goes back to U.S. District Court Judge Louis L. Stanton he will be well aware that Viacom tried to have him bounced from the case. While Judge Stanton (who has almost 30 years on the bench and is pictured above) may try not to hold this against Viacom, he’s only human, and there’s no knowing to what extent this will subtly bias him against Viacom. After all, one of the most important rules of good lawyering is try to stay on the right side of the judge.*

*That’s why lawyers invariably laugh at every joke made by a judge in their case, and even (I have seen this) research the judge’s hobbies and make subtle comments about it. If the judge’s hobbies include professional baseball, you can be sure one of the lawyers will comment, “great (tough) game last night, Your Honor.”

Given the low likelihood that the request will succeed, was asking for reassignment a prudent risk for Viacom to take? I think not. For the Second Circuit to reassign a case on remand following summary judgment is rare, so this is a long shot for Viacom. As Justice (then Second Circuit Appeals Court Judge) Sotomayor observed in 2001, reassignment on remand occurs only where there are “unusual circumstances,” such as “substantial difficulty in putting out of his or her mind previously-expressed views or findings determined to be erroneous” or to “preserve the appearance of justice.” (Martens v. Thomann). The two cases cited by Viacom (U.S. v. Robins and Scott v. Perkins) are not to the contrary.

Viacom has made no effort to show that Judge Stanton falls under this narrow exception. The only “appearance of injustice” is that the judge has ruled against Viacom in two summary judgment motions. The majority of the judge’s rulings were upheld in Viacom’s first appeal, showing that the “appearance of injustice” is often in the eye of the person receiving the justice.

If anything, the fact that Viacom v. Youtube is a large, complex and long-lived case with which Judge Stanton is intimately familiar is good reason not to remand the case to a new district court judge.

Clearly, Viacom is fed up with Judge Stanton and wants to get out of his courtroom. However, it has taken a calculated risk with low odds in its favor. By asking that its case be reassigned in the event of a remand Viacom’s lawyers are more likely to have shot their client in the foot than to have advanced its cause.

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 6, 2013 | Copyright

An unusual copyright suit recently filed in federal court in Boston is worth a brief comment.

Here are the facts.

In July 2012 someone wrote an offensive, defamatory “complaint” about a Boston attorney on the website Ripoff Report. Because a federal statute (47 USC § 230) protects Ripoff Report from liability for defamatory user generated content (“UGC”), the lawyer could not force Ripoff Report to remove the defamation from the site.* However, he came up with a clever (but, as we shall see, probably ineffective) work-around.

*Ripoff Report does not voluntarily take down UGC.

The lawyer sued the original poster for defamation in Massachusetts superior court, and obtained a default judgment. As part of the relief he was assigned the copyright in the defamatory posting (or, power of attorney giving him the right to assign copyright ownership to himself). He then demanded that Ripoff Report take down the copyrighted material. Ripoff Report refused, and the lawyer has now sued Ripoff Report in federal court in Boston for copyright infringement.

Setting aside the question of whether transferring copyright ownership of defamatory material is a proper remedy for defamation (this implicates First Amendment issues), and whether the defamation at issue is even entitled to copyright protection (it is very brief and non-creative), can the lawyer use this strategy to obtain removal of the defamation from Ripoff Report?*

*More precisely, can the threat of damages for copyright infringement compel Ripoff Report to take down the defamation?

At first blush the attorney’s copyright suit against Ripoff Report faces two significant problems: first, whether the Massachusetts state court had the legal authority to transfer the copyright to him, and second, whether the original author granted rights to Ripoff Report that trump any rights the state court could give to the lawyer.

Let’s take these in reverse order. Paragraph 6 of the Ripoff Report’s terms of service state: “by posting information or content to any public area of www.RipoffReport.com, you automatically grant, and you represent and warrant that you have the right to grant, to [Ripoff Report ] an irrevocable, perpetual, fully-paid, worldwide exclusive license to use, copy, perform, display and distribute such information and content ….” In order to post on Ripoff Report a user must register on the site and agree to be bound by a clickwrap agreement that includes these TOS.

Can an assignment (whether by the court or even the original author) deprive Ripoff Report of this license? Clearly not. Ripoff Report, not the original poster, owns the copyright in this content. (See, e.g., Davis v. Blige, 2nd Cir. 2007 (“exclusive license … conveys an ownership interest”).

The fact that Ripoff Report owns the copyright should end the matter right there. The Massachusetts court had no authority to transfer ownership in a copyright that was not even owned by the defaulting defendant. However, there is the further question of whether the Massachusetts state court had the authority to transfer ownership to the attorney, even if the defendant had still owned the copyright. The copyright statute provides that “when an individual author’s ownership of a copyright, … has not previously been transferred voluntarily by that individual author, no action by any governmental body … purporting to … transfer, or exercise rights of ownership with respect to the copyright … shall be given effect except as provided under title 11.”

Title 11 is the federal bankruptcy statute. Bankruptcy was not implicated in this case, and in any event the bankruptcy laws are administered by the federal bankruptcy courts, not the state courts. Thus, the state court did not have the authority to transfer any rights of ownership in the defamatory material, and therefore any rights the attorney could have acquired by reason of the court order are of no legal effect. Because the attorney does not hold the copyright he has no valid copyright claim against Ripoff Report, and the case should be dismissed.

[Note: I have not provided the name of the attorney or the case, or a link to any pleadings, because I am hoping to spare the attorney involved any further discomfort arising from the Streisland Effect.]

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 1, 2013 | Copyright

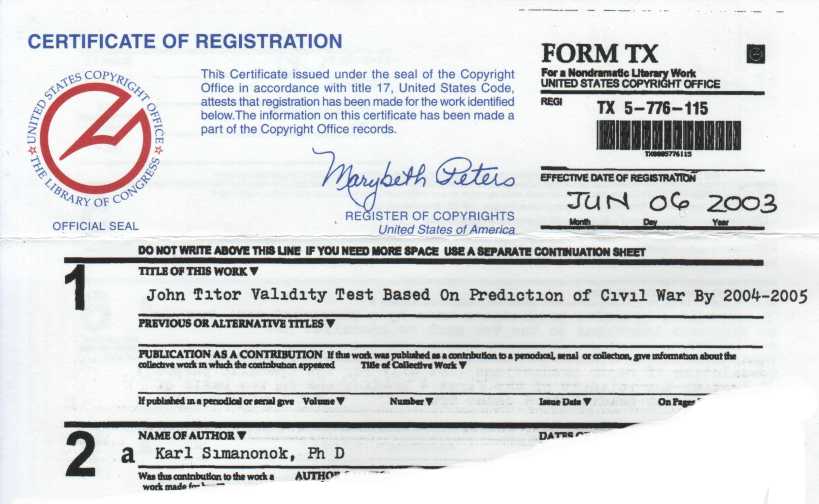

Copyright registration requirements can get quirky, and if they aren’t handled properly can result in dismissal of a copyright infringement case (valid registration being a requirement before an infringement case can be filed). An invalid or defective registration can deep-six a copyright plaintiff’s suit on a technicality.

The Fourth Circuit addressed a number of issues associated with copyright registration in Metropolitan Regional Information Systems, Inc. v. American Home Realty Network, Inc. (July 17, 2013), one of which is whether the requirement that assignment of a copyright be in writing (17 U.S.C. § 204) may be satisfied by an electronic signature under E-Sign, 15 U.S.C. § 7001.

In what appears to be the first appellate decision on the question of whether E-Sign applies to the copyright statute’s signed writing requirement, the Fourth Circuit held that it does, and that the e-signature at issue in this case (a click-wrap agreement), was a valid assignment:

The issue we must yet resolve is whether a subscriber, who “clicks yes” in response to MRIS’s electronic TOU prior to uploading copyrighted photographs, has signed a written transfer of the exclusive rights of copyright ownership in those photographs consistent with Section 204(a) [of the Copyright Act]. Although the Copyright Act itself does not contain a definition of a writing or a signature, much less address our specific inquiry, Congress has provided clear guidance on this point elsewhere, in the E-Sign Act.

The E-Sign Act, aiming to bring uniformity to patchwork state legislation governing electronic signatures and records, mandates that no signature be denied legal effect simply because it is in electronic form. … Additionally, “a contract relating to such transaction may not be denied legal effect, validity, or enforceability solely because an electronic signature or electronic record was used in its formation.” The E-Sign Act in turn defines “electronic signature” as “an electronic sound, symbol, or process, attached to or logically associated with a contract or other record and executed or adopted by a person with the intent to sign the record.”

Although the E-Sign Act states several explicit limitations, none apply here. The Act provides that it “does not . . . limit, alter, or otherwise affect any requirement imposed by a statute, regulation, or rule of law . . . other than a requirement that contracts or other records be written, signed, or in nonelectric form[.]” … Because Section 204(a) requires transfers be “written” and “signed,” a plain reading of Section 7001(b) indicates that Congress intended the provisions of the E-Sign Act to “limit, alter, or otherwise affect” Section 204(a).

While the court’s ruling on E-Sign is significant (if for no other reason than that it is the first clear appellate ruling on this issue since the federal law was enacted in 2000), this case is important in other respects as well. The court held that websites (in this case an MLS service) can acquire exclusive copyright ownership from users using clickthrough agreements, and addressed the registration requirement for collective works.

Metropolitan Regional Information Systems, Inc. v. American Home Realty Network, Inc. (July 17, 2013)

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 31, 2013 | CFAA

This week’s internal report by MIT on its handling of the Aaron Swartz case may be an appropriate time to note that the sound and fury over the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (the “CFAA”) is not limited to its use in criminal cases like the Swartz prosecution. The controversy extends to the use of this law in civil cases as well.*

*The CFAA may be used as either a civil or a criminal law. However, the words of the statute must mean the same thing in each context. As the court noted in the case discussed in this post, “it is not possible to define authorization narrowly for some CFAA violations and broadly for others.”

In my July 2nd post on AMD v. Feldstein I noted that the case had given rise to two note-worthy decisions. The May 15, 2013 decision, discussed in that post, involved the legalities of the former-AMD employees’ alleged solicitation of current AMD employees in violation of non-solicitation agreements. However, Massachusetts Federal District Court Judge Timothy Hillman issued a second opinion in the case on June 10, 2013, ruling on the defendant-employees’ motion to dismiss claims of civil liability under the CFAA.

Judge Hillman’s June 10th opinion reflects the struggle within the federal courts nationally over how to apply the CFAA. The controversy focuses on the section of the law that imposes criminal and civil penalties on –

whoever … intentionally accesses a computer without authorization or exceeds authorized access, and thereby obtains … information from any protected computer. 18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(2)(C).*

*As Judge Hillman observed, “The breadth of this provision is difficult to understate.”

I discussed the courts’ varied interpretations of this provision in some detail in an August 2012 post. As I stated there, “the issue, on which the federal courts cannot agree, is whether an employee who has authorized access to a computer, but uses that access for an illegal purpose — typically to take confidential information in anticipation of resigning to start a competing company or join one — violates the CFAA.” In that post I discussed several of the conflicting decisions over this issue, including the Ninth Circuit’s influential en banc holding in U.S. v. Nosal.

In considering how to apply the CFAA in this case Judge Hillman described the two possible interpretations of the CFAA. The first, a “technological model of authorization,” requires that an employee violate a technologically implemented barrier in order for his actions to give rise to a violation. Under this model, which the court described as the “narrow interpretation,” the employee would have to (for example) use someone else’s login credentials to access his employer’s computer, or break into (hack) the computer. Another way to view the “narrow interpretation” of the CFAA is that the phrase “without authorization” in the statute is limited to outsiders who do not have permission to access the employer’s computer in the first place.

Under the second model, described as the “broader interpretation,” the employee would be liable under the CFAA if he used a valid password to access information for an improper purpose, for example, obtaining confidential or trade secret information that will be provided to the employee’s new employer, or to a competitor of the current employer.

As Judge Hillman noted, the only First Circuit case to address the scope of the CFAA – EF Cultural Travel BV v. Explorica, Inc. – only created uncertainty over how to apply the statute. At least one Massachusetts district court judge has viewed EF Cultural as an endorsement of the broader interpretation. Guest-Tek Interactive Entm’t, Inc. v. Pullen (Gorton, J. 2009).

Judge Hillman, however, disagreed, distinguishing EF Cultural and concluding that the facts in that case shift it into the realm of “access that exceeds authorization” rather than permitted access for an unauthorized purpose. In what seems to be a clear nod to the Ninth Circuit in Nosal, he held that “as between a broad definition that pulls trivial contractual violations into the realm of federal criminal penalties, and a narrow one that forces the victims of misappropriation and/or breach of contract to seek justice under state, rather than federal, law, the prudent choice is clearly the narrower definition.”*

*A recent case from the district of New Hampshire appears to have reached the same conclusion. Wentworth-Douglas Hospital v. Young & Novis Prof. Assoc. (June 29, 2012).

This is the conclusion that the former AMD employee-defendants wanted the court to reach on their motion to dismiss the CFAA count. However, it turned out to be somewhat of a pyrrhic victory for them.

Although the judge found that “the narrower interpretation” of the CFAA “is preferable” and found that AMD’s “allegations are … insufficient to sustain a CFAA claim under a narrow interpretation of the CFAA,” he declined to dismiss the CFAA claims against the defendants, noting that “this is an unsettled area of federal law, and one where the courts have yet to establish a clear pleading standard.” Instead, he deferred action on this claim until the factual record is complete, meaning the conclusion of discovery.

And, if it was the defendants’ hope to dismiss the federal CFAA claim in order to force the case into state court (which is unclear, since AMD also pleaded diversity jurisdiction), not only did they fail to accomplish this by means of this motion, but the court went so far as to note that “even if the CFAA claims are dismissed at a later date, the pendant state law claims need not be remanded to state courts. … It would be extremely inefficient to remand this case to state court given the quantity of evidence already presented to this Court.”

Bottom line: the defendants won their central legal argument, but did not get their reward. And, this section of the CFAA remains in limbo in the First Circuit, pending final word from the First Circuit Court of Appeals on its proper interpretation.

Advanced Micro Devices, Inc.v. Feldstein