[Update: Perlmutter’s challenge to her termination was rejected by a district court judge on July 30, 2025. However, on September 10, 2025 the DC Circuit reversed that ruling and issued an injunction ordering that Perlmutter be reinstated as Register of Copyrights:

In sum, all of the preliminary-injunction factors weigh in favor of granting an injunction pending appeal. Perlmutter has shown a likelihood of success on the merits of her claim that the President’s attempt to remove her from her post was unlawful because she may be discharged only by a Senateconfirmed Librarian of Congress. She also has made the requisite showing of irreparable harm based on the President’s alleged violation of the separation of powers, which deprives the Legislative Branch and Perlmutter of the opportunity for Perlmutter to provide valuable advice to Congress during a critical time. And Perlmutter has shown that the balance of equities and the public interest weigh in her favor because she primarily serves Congress and likely does not wield substantial executive power, which greatly diminish the President’s interest in her removal. For the foregoing reasons, we grant Perlmutter’s requested injunction pending appeal.]

On May 9, 2025, the U.S. Copyright Office released what should have been the most significant copyright policy document of the year: Copyright and Artificial Intelligence – Part 3: Generative AI Training. This exhaustively researched report, the culmination of an August 2023 notice of inquiry that drew over 10,000 public comments, represents the Office’s most comprehensive analysis of how large-scale AI model training intersects with copyright law.

Crucially, the report takes a skeptical view of broad fair use claims for AI training, concluding that such use cannot be presumptively fair and must be evaluated case-by-case under traditional four-factor analysis. This position challenges the AI industry’s preferred narrative that training on copyrighted works is categorically protected speech, potentially exposing companies to significant liability for their current practices.

Instead of dominating the week’s intellectual property news, the report was immediately overshadowed by an unprecedented political upheaval that raises fundamental questions about agency independence and the rule of law.

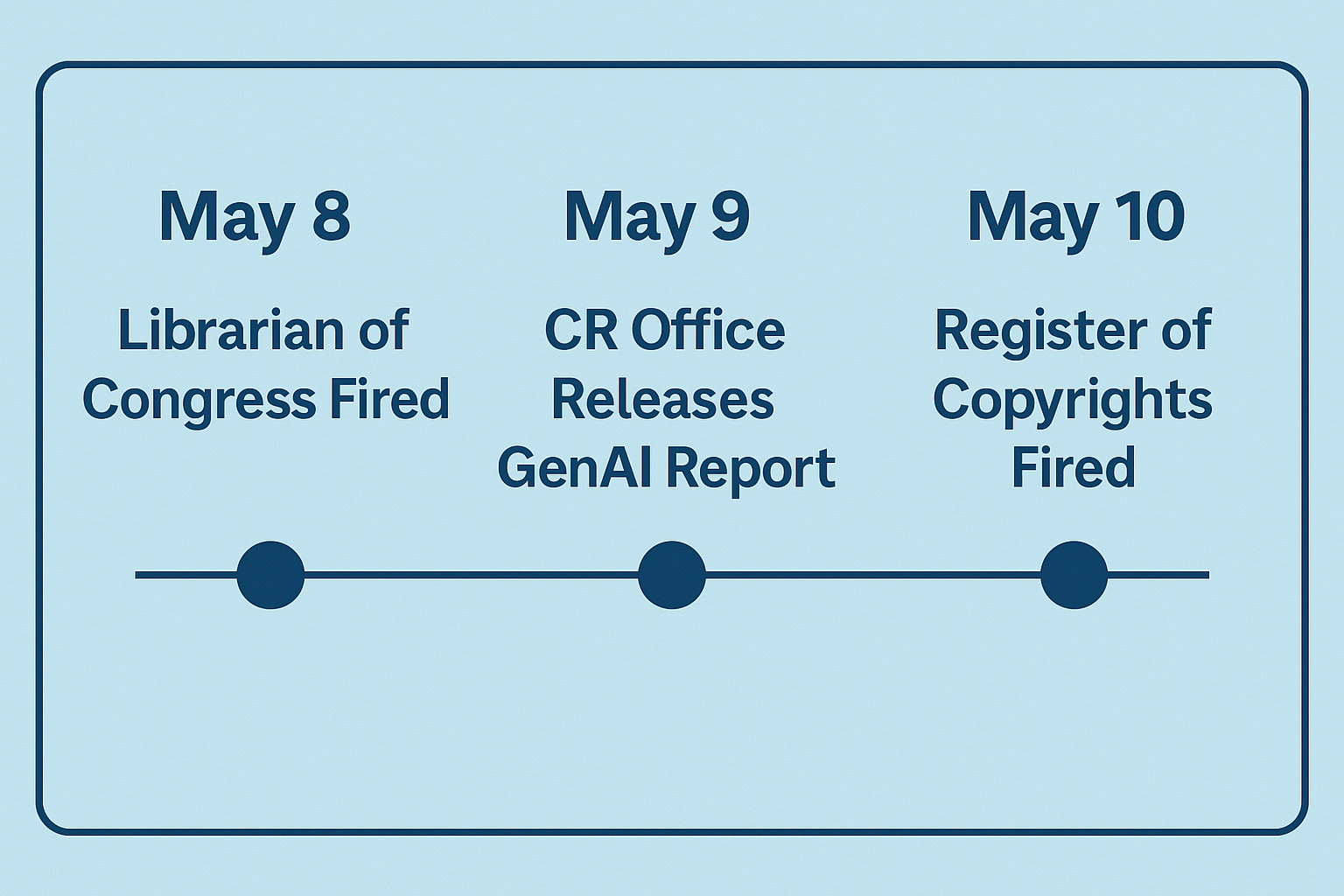

Three Days in May

The sequence of events reads like a political thriller. On May 8—one day before the report’s release—Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden was summarily dismissed. Hayden held the sole statutory authority to hire and fire the Register of Copyrights. The report was issued on May 9, and the next day, May 10, Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter was fired by President Trump. Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche was appointed acting Librarian of Congress on May 12.

On May 22 Perlmutter filed suit against Blanche and Trump, alleging that her removal violated both statutory procedure and the Appointments Clause, and seeking judicial restoration to office.

The timing invites an obvious inference: the report’s conclusions displeased either the administration, powerful AI industry advocates, or both. As has been attributed to FDR, “In politics, nothing happens by accident. If it happens, you can bet it was planned that way.”

An Unprecedented “Pre-Publication” Label

The report itself carries a peculiar distinction. In the Copyright Office’s 128-year history of issuing over a hundred reports and studies, this marks the first time any policy document has been labeled a “pre-publication version.” A footnote explains that the Office released this draft “in response to congressional inquiries and expressions of interest from stakeholders,” promising a final version “without any substantive changes expected in the analysis or conclusions.”

any policy document has been labeled a “pre-publication version.” A footnote explains that the Office released this draft “in response to congressional inquiries and expressions of interest from stakeholders,” promising a final version “without any substantive changes expected in the analysis or conclusions.”

Whether Perlmutter rushed the draft online sensing her impending dismissal, or whether external pressure demanded early release, remains unexplained. What is clear is that this unusual designation complicates the document’s legal authority.

The Copyright Office as Policy Driver

Understanding the significance of these events requires recognizing that the Copyright Office is far more than a record-keeping/collection body. Congress expressly directs it to “conduct studies” and “advise Congress on national and international issues relating to copyright.” The Office serves as both a de facto think tank and policy driver in copyright law, with statutory responsibilities that make reports like this central to its mission.

The generative AI report exemplifies this role. It distills an enormous public record into a meticulous analysis of how AI training intersects with exclusive rights, market harm, and fair-use doctrine. The document is detailed, thoughtful, and comprehensive—representing the kind of scholarship you would expect from the nation’s premier copyright authority. Anyone seeking a balanced primer on generative AI and copyright should start here.

market harm, and fair-use doctrine. The document is detailed, thoughtful, and comprehensive—representing the kind of scholarship you would expect from the nation’s premier copyright authority. Anyone seeking a balanced primer on generative AI and copyright should start here.

Legal Weight in Limbo

While Copyright Office reports carry no binding legal precedent, federal courts often give them significant persuasive weight under Skidmore deference (Skidmore v. Swift, U.S. 1944), recognizing the Office’s particular expertise in copyright matters. The “pre-publication” designation, however, creates unprecedented complications.

Litigants will inevitably argue that a self-described draft lacks the settled authority of a finished report. If a final version emerges unchanged, that objection may evaporate. But if political pressure forces revisions or withdrawal, the May 9 report could become little more than a historical curiosity—a footnote documenting what the Copyright Office concluded before political intervention redirected its course.

The Chilling Effect

Even if the timing of the dismissals of the Librarian of Congress and Register of Copyrights on either side of the day the report was released was coincidental—a proposition that strains credulity—the optics alone threaten the Copyright Office’s independence. Future Registers will understand that publishing conclusions objectionable to influential constituencies, whether in the West Wing or Silicon Valley, can cost them their jobs.

This perception could chill precisely the kind of candid, expert analysis that Congress mandated the Office to provide. The sequence of events may discourage future agency forthrightness or embolden those seeking to influence administrative findings in politically fraught areas like AI regulation.

What Comes Next

For now, the “pre-publication” draft remains the Copyright Office’s most authoritative statement on generative AI training. Whether it survives intact, is quietly rewritten, or is abandoned altogether will reveal much about the agency’s future independence and the balance of power between copyright doctrine and the emerging AI economy.

The document currently exists in an unusual limbo—authoritative yet provisional. Its ultimate fate may signal whether copyright policy will be shaped by legal expertise and public input, or by political pressure and industry influence.

Until that question is resolved, the report stands as both a testament to rigorous policy analysis and a cautionary tale about the fragility of agency independence in an era of unprecedented technological and political change. The stakes extend far beyond copyright law—they touch on the fundamental question of whether expert agencies can fulfill their statutory duties free from political interference when their conclusions prove inconvenient to powerful interests.

The rule of law hangs in the balance, awaiting the next chapter in this extraordinary story.