by Lee Gesmer | Dec 7, 2025 | Employment

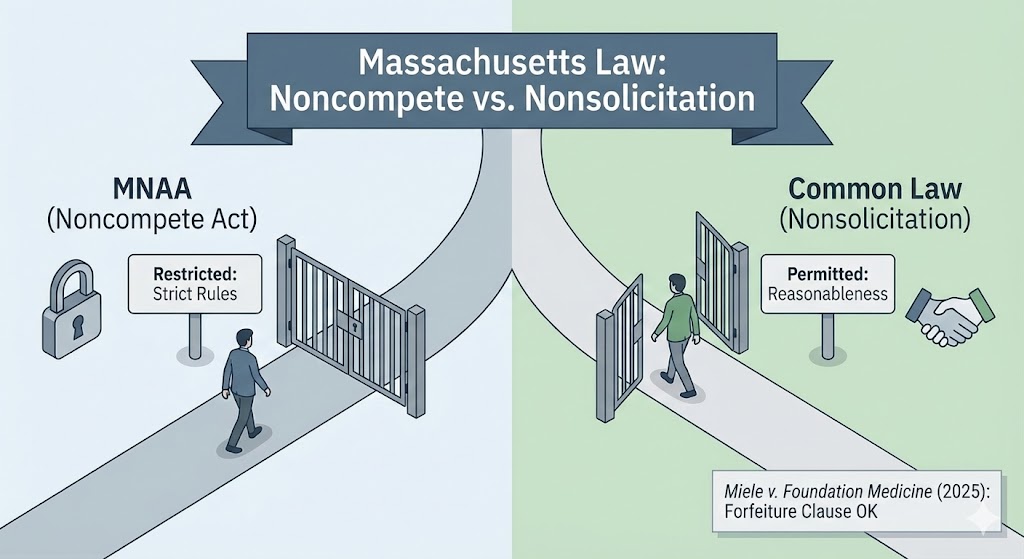

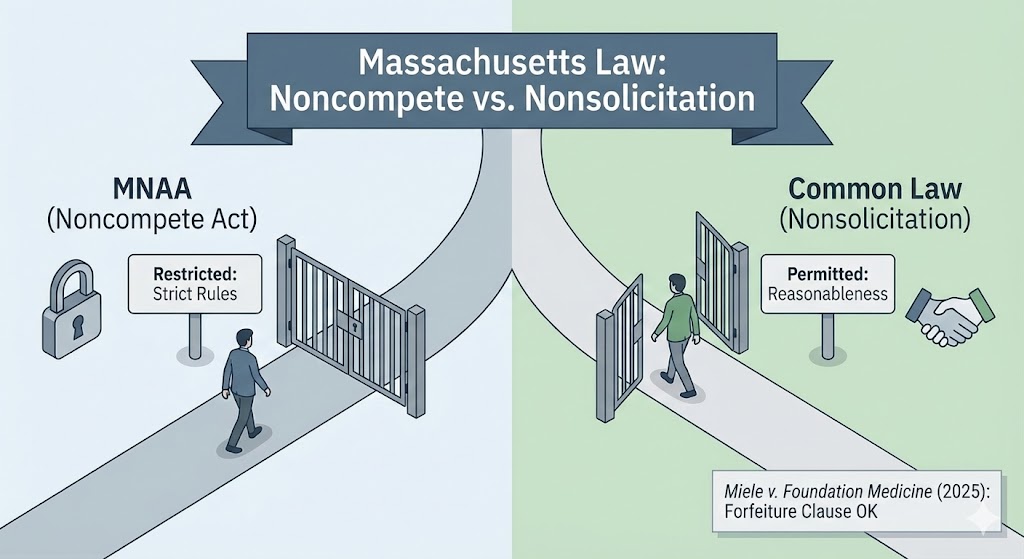

When the Massachusetts Noncompetition Agreement Act (MNAA) took effect in October 2018, I described the law in detail and wrote that employers and employees were entering “a new era” in noncompete law. The statute imposed formalities, created new employee protections, and limited the enforceable duration of noncompetes. But it also drew a set of carefully worded exclusions – most notably for nonsolicitation agreements. I predicted that those exclusions would become critical as employers adjusted to this new law.

Seven years later, the Supreme Judicial Court has now decided its first significant case interpreting the statute, Miele v. Foundation Medicine, Inc. (2025). The decision answers a narrow question, but it carries substantial practical consequences. The court held that the MNAA does not apply when an employer conditions severance pay on compliance with an employee-nonsolicitation covenant. In other words, adding a forfeiture-of-benefits clause to a nonsolicit does not convert it into a noncompetition agreement.

What the MNAA Regulates – And What It Doesn’t

The MNAA regulates agreements that bar a former employee from engaging in post-employment competition. To be enforceable, such agreements must satisfy a gauntlet of statutory onerous requirements: advance notice, a written agreement signed by both parties, the right to consult counsel, a one-year limit on duration (with narrow exceptions), and “garden leave” or other agreed-upon consideration.

And, importantly, the MNAA includes “forfeiture for competition” agreements under the definition of noncompetition agreements. This was designed to prevent employers from avoiding the statute’s requirements by replacing a noncompete with a compensation-forfeiture clause that accomplishes the same result. In other words, employers should not be able to sidestep limits on noncompetes by changing the mechanism of enforcement.

The statute is sufficiently burdensome that employee noncompete agreements, once a routine feature of employment contracts in Massachusetts, are now seldom used.

But the statute does not sweep in every type of restrictive covenant. Its definition of “noncompetition agreement” excludes several categories, including:

- Employee and customer nonsolicitation covenants

- Confidentiality and intellectual-property assignment provisions

- Covenants linked to the sale of a business

As I noted in 2018, those exclusions matter. A well-drafted nonsolicitation clause can serve much of the protective function that noncompetes historically played. The MNAA left those covenants to be governed by common-law reasonableness standards rather than the statute’s rigid framework.

The Dispute in Miele

Susan Miele signed an employee-nonsolicitation agreement when she joined Foundation Medicine in 2017. When she left the company in 2020, she entered into a “transition agreement” providing substantial severance benefits. That agreement incorporated the earlier nonsolicitation covenant and added a forfeiture clause: if she breached any of her continuing obligations, she would forfeit unpaid benefits and repay benefits already received.

After Miele joined a competitor, Foundation Medicine alleged that she solicited several FMI employees during the one-year restricted period. The company stopped payments and demanded repayment. Miele sued, arguing that the forfeiture provision was an unenforceable “forfeiture for competition” agreement subject to the MNAA.

She took this argument all the way to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and lost.

The SJC’s Holding: A Nonsolicitation Clause Remains a Nonsolicitation Clause

The SJC’s analysis turned on the statute’s definitions. The MNAA:

- Excludes nonsolicitation agreements from the category of noncompetition agreements; and

- Defines forfeiture-for-competition agreements as a type of noncompetition agreement.

Given those two premises, the court held that a forfeiture triggered by a breach of a nonsolicitation covenant is not a “forfeiture for competition agreement” under the MNAA. The forbidden conduct was solicitation, not competition itself. Because the underlying covenant falls outside the statute, the forfeiture remedy does not bring it back within the statute’s scope.

In short: the presence of a forfeiture provision does not change the legal identity of the underlying restrictive covenant. If the covenant is a nonsolicitation clause, the MNAA does not apply.

Implications Going Forward

Miele gives employers and employees much-needed clarity, and it confirms several practical realities about the MNAA:

- Nonsolicitation provisions remain outside the statute, even when backed by serious financial consequences. A severance agreement that conditions payment on compliance with a nonsolicitation covenant does not trigger the MNAA merely because the remedy is forfeiture or repayment. These provisions will continue to be governed by pre-2018 common law.

- The MNAA’s reach depends on the nature of the restricted activity, not the chosen remedy. If an agreement penalizes an employee for working for a competitor, it is a forfeiture-for-competition agreement subject to the statute. If it penalizes solicitation, it is not. The drafting focus rests on the conduct being restricted, not the mechanism of enforcement.

- Common-law reasonableness remains the governing framework for nonsolicitation covenants. Duration, scope, legitimate business interest, and employee role still matter. Parties should expect future litigation over what counts as “solicitation,” a concept the common law has never cleanly defined. I wrote about this perplexing topic more than ten years ago in Nudge, Nudge, Wink, Wink – Are You “Soliciting” in Violation of an Employee Non-Solicitation Agreement?

- Separate statutes still matter. Miele does not insulate forfeiture clauses from scrutiny under the Massachusetts Wage Act or other employment statutes. Severance structured as earned compensation, for example, may present Wage Act issues if subject to forfeiture.

- Expect heavier reliance on nonsolicitation + severance-forfeiture structures. The decision validates a drafting strategy employers began adopting after 2018: use narrower covenants that avoid the MNAA altogether, coupled with meaningful financial incentives for compliance.

Conclusion

When the MNAA was enacted, the open question was how far courts would go in applying its protective rules beyond traditional noncompetes. Miele provides a clear boundary: the MNAA governs restraints on competitive employment, not every restrictive covenant that may influence post-employment behavior. Nonsolicitation clauses, even with substantial economic consequences attached, remain on the common-law side of the line.

Employers will undoubtedly make fuller use of that space. Employees and their counsel will scrutinize whether a provision labeled “nonsolicitation” is in substance a broader restriction. And the statute will continue to generate interpretive questions as parties test its edges.

by Lee Gesmer | Nov 11, 2025 | Copyright, DMCA/CDA

Can your internet provider be held liable for what you download? That’s the question the Supreme Court will wrestle with on December 1, when it hears Sony Music Entertainment v. Cox Communications – a case that could reshape how the internet handles copyright enforcement.

Back in May 2024 I wrote about the Fourth Circuit’s February 2024 decision in this case, breaking down the court’s divergent rulings on vicarious and contributory liability. Now the stakes have gotten even higher. The Supreme Court has agreed to hear Cox’s appeal, and the case has attracted an unusual ally: the U.S. Solicitor General, whose brief warns that the Fourth Circuit’s approach threatens universal internet access.

The Case in Brief

Cox Communications is one of the largest ISPs in the United States. Sony and other record labels sent Cox hundreds of thousands of infringement notices identifying subscribers who used peer-to-peer networks to trade copyrighted songs. The labels argued Cox knew certain customers were serial infringers but failed to disconnect them, preferring to keep collecting subscription fees. A jury agreed and awarded a record $1 billion in damages.

The Fourth Circuit split the verdict. It reversed the finding of vicarious liability, holding that Cox’s flat-fee model meant it earned the same revenue whether subscribers infringed or not – therefore Cox received no “direct financial benefit” from infringement. But it affirmed contributory liability, finding that Cox knew specific subscribers were repeat infringers and continued providing them internet service, which materially contributed to the infringement.

Because the jury’s award didn’t distinguish between the two theories, the court vacated the entire damages and remanded for a new trial on contributory infringement alone. Cox appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

What’s Before the Supreme Court

Cox argues the Fourth Circuit fundamentally misread copyright law. The company points to the Supreme Court decisions in Sony v. Universal (the 1984 “Betamax case”) and MGM v. Grokster (2005), both holding that secondary liability requires intentional encouragement or inducement of infringement – not mere knowledge that a service could be misused. Cox’s central theme can be summarized as: “We sell internet access, not infringement.”

Importantly, the U.S. Solicitor General agrees with Cox. The government warned that the Fourth Circuit’s rule cannot be reconciled with precedent and would threaten universal internet access. If ISPs face liability simply for knowing users might infringe again, they’ll over-enforce – cutting off schools, libraries, and households based on unverified accusations.

Sony sees it differently. The labels argue Cox wasn’t a neutral conduit but made a calculated business decision: it received hundreds of thousands of specific notices yet chose to keep subscribers connected to preserve revenue. This isn’t passive knowledge – it’s complicity. They also point to Cox’s allegedly ineffective repeat infringer policy, which Sony claims was designed to retain revenue rather than stop infringement.

Why Didn’t the DMCA Control This Case?

Normally, Internet providers like Cox are protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which gives online services a “safe harbor” from liability for their users’ infringement. To qualify, an ISP must adopt and reasonably enforce a repeat infringer policy – in other words, it has to disconnect customers who repeatedly violate copyright law after proper notice.

Cox, however, lost that protection years ago. In an earlier case the Fourth Circuit found that Cox had a policy on paper but didn’t actually enforce it. Internal emails showed that employees routinely reinstated known infringers to keep their monthly payments coming. That decision disqualified Cox from the DMCA’s safe harbor for the period covered in the Sony lawsuit. BMG Rights Management v. Cox (2018).

As a result, this case proceeded outside the DMCA framework, under the older, judge-made rules of secondary copyright liability – the doctrines of contributory and vicarious infringement. The Supreme Court is now being asked to decide how far those doctrines can reach when the statutory safe harbor no longer applies.

However, both sides know that if the Court sees Sony v. Cox as a one-off “Cox-was-a-bad-actor” case, the Court may decide it narrowly, or dismiss the broader policy concerns. The parties have worked hard to frame the case as not an edge case, arguing that there is industry-wide noncompliance with the safe harbor and that the case has cross-industry implications far beyond Cox.

What’s Next

The Court hears arguments on December 1, with a decision expected by June 2026.

If the Court accepts Sony’s theory – that an ISP can be contributorily liable simply for continuing to provide internet access to a subscriber after receiving infringement notices – the decision would push secondary liability far beyond the Sony/Grokster framework. Cox warns that this effectively creates a “two-notices-and-terminate” rule, forcing ISPs to cut off entire households, dorms, hospitals, and even downstream networks based on a small number of unverified accusations. Cox argues that this approach conflicts with Grokster which requires intentional, affirmative conduct to support liability; merely supplying multi-use communications infrastructure to the public on uniform terms, it argues, cannot be a culpable act.

A ruling for Sony would reverberate beyond broadband. Cloud hosts, campus networks, content delivery networks (such as Cloudflare and Akamai), and payment processors – all of whom receive automated copyright notices – would feel pressure to over-terminate users to avoid the inference that they “purposefully” facilitated infringement. The DMCA’s safe-harbor regime, which contemplates reasonable repeat-infringer policies, would become secondary to a broader judge-made duty to disconnect first and ask questions later. In that scenario, copyright enforcement would move deeper into the internet’s basic plumbing, reshaping how infrastructure providers manage risk and potentially constraining access for lawful users across entire networks.

by Lee Gesmer | Oct 20, 2025 | Copyright

“The absolute transformation of everything that we ever thought about music will take place within 10 years, and nothing is going to be able to stop it. I see absolutely no point in pretending that it’s not going to happen. I’m fully confident that copyright, for instance, will no longer exist in 10 years.”

– David Bowie, 2002

In 1994, Stanford copyright scholar Paul Goldstein coined a phrase that captured the imagination of anyone following the collision between music and technology. He foresaw the arrival of the “Celestial Jukebox” – a future in which every song ever recorded would be available instantly, anywhere, from a digital cloud. Three decades later, that vision has come to pass. We can stream millions of tracks on Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, and Amazon. The jukebox is celestial.

But Bowie’s prophecy that copyright would vanish in the process proved wrong. Instead, copyright law has persisted, adapting – sometimes awkwardly, sometimes elegantly – to every new medium.

What follows is a tour through the architecture of the business side of music copyright. To try to tie it all together I’ve used Dolly Parton’s song I Will Always Love You. My thanks to tech entrepreneur and veteran music disruptor Jeff Price, who used this song for this purpose in a presentation I saw years ago.

I Will Always Love You – One Song, Two Copyrights

When Dolly Parton wrote and originally recorded I Will Always Love You in 1973, she created two distinct copyrights. The first, in the musical work – the melody and lyrics – was hers to keep through her own publishing company, Owe-Par Publishing. The second, in the sound recording, belonged to RCA Records, which released her performance under contract with her.

The fact that most music has two separate copyrights – the composition and the sound recording – is the starting point for almost every legal question in the music business. Legal ownership of the copyright in the composition is often referred to as the publishing rights. Ownership of the sound recording is known as rights in the master recording, often referred to simply as the master.

When Whitney Houston recorded her 1992 version of I Will Always Love You for the film The Bodyguard, she and her label, Sony Records, created a new sound recording – a separate copyright from Dolly Parton’s original 1974 recording. But the musical composition – the underlying melody and lyrics – remained Dolly Parton’s property through her publishing company.

Public Performances and the PROs

One of the exclusive rights held by a copyright owner is the right of public performance. Dolly Parton owns the public performance right in her composition.

Every time I Will Always Love You plays in public – whether in a restaurant, on radio, on television, or through a digital stream – that is a public performance, and Dolly Parton is owed a royalty. The U.S. system for collecting these payments relies on four performing rights organizations, or “PROs”: ASCAP, BMI, SESAC and GMR. Each PRO offers a “blanket license” that allows a venue or broadcaster to use an entire catalog of songs without negotiating with each songwriter individually.

Under these licenses, venues, broadcasters, and digital services pay royalties to the performing rights organizations, which in turn distribute royalties to the songwriters and publishers they represent. It is a quiet but remarkably effective system of collective licensing – largely invisible to the public – that ensures the creators of songs, often overshadowed by the artists who perform them, are compensated whenever their music is publicly performed.

Mechanical Royalties and the Compulsory License

Suppose you want to record and sell your own version of I Will Always Love You, referred to as a “cover.” Do you need Dolly’s permission? Surprisingly, you don’t. Section 115 of the Copyright Act grants a compulsory mechanical license. Once a song has been released to the public, anyone may record and distribute a cover version as long as they pay the owner of the composition a statutory royalty – currently 12.4 cents per copy for songs under five minutes.

When Whitney Houston’s label, Sony, decided to record a cover of I Will Always Love You for The Bodyguard, it obtained a mechanical license covering the use of Dolly Parton’s composition. In most cases, this process is handled by the Harry Fox Agency, which serves as an intermediary between record labels and music publishers, collecting and distributing mechanical royalties. Because the license is compulsory under §115 of the Copyright Act, Parton could not refuse permission for the recording, but she remained entitled to receive the royalties generated by every reproduction and public performance of the song.

The system may sound bureaucratic, but it dates back to 1909, when Congress first created compulsory licenses to encourage the spread of new technologies – from player pianos to phonographs. The goal was to balance artistic control with public access, and it remains a defining feature of American music law.

Covers and the Question of Control

The concept of a compulsory license is not without controversy, and not all artists agree with it. Bob Dylan admired Jimi Hendrix’s transformative cover of All Along the Watchtower, saying that he now performs it “as a tribute to Hendrix.” Prince, on the other hand, resented the very idea. “There’s this thing called the compulsory license law,” he once complained, “which allows artists, through record companies, to take your music, at will, without your permission. And that doesn’t exist in any other art form.”

Prince was right about the uniqueness of music’s legal regime. No one can compel an author to let others rewrite a novel, or a filmmaker to let others reshoot a movie. But musicians have long accepted that their songs can – and will – be covered. It’s a reminder that copyright in music has always existed in tension with the culture of performance and reinvention.

The Sync License and the Bodyguard Deal

When The Bodyguard film featured Whitney Houston’s rendition of I Will Always Love You, two different sets of rights had to be cleared. The film’s producers needed a synchronization, or “sync,” license from Dolly Parton for the musical composition, and a master-use license from Sony Records for Houston’s sound recording. Unlike the statutory license for sound recordings, sync licenses must be negotiated and often are highly lucrative.

Parton’s ownership of her publishing rights gave her a decisive advantage. Early in her career, she founded her own publishing company, an unusual step for a young performer in the early 1970s. That decision gave her control over how her songs were used and allowed her to negotiate directly when Hollywood came calling. She later recalled how she once turned down Elvis Presley’s request to record I Will Always Love You because Colonel Tom Parker (Presley’s infamous manager) demanded half her publishing rights. It was, she said, one of the hardest business decisions of her life. Reportedly, keeping the publishing rights to that song has earned her over $10 million.

Streaming and the Music Modernization Act

The arrival of digital streaming shattered the clean boundaries that once separated reproduction from performance. Every stream is both: a reproduction of the composition and a public performance. But the performance rights differ between the two copyrights. For the musical composition, any public performance – whether on terrestrial radio, in a restaurant, or through a stream – generates a royalty for the songwriter. For the sound recording, however, the public performance right is narrower. It applies only to digital transmissions like streaming and internet radio, not to traditional AM/FM broadcasts.

This means that when Houston’s cover of I Will Always Love You plays on Spotify, Dolly Parton earns performance royalties as the songwriter, and Whitney Houston’s estate and Sony earn performance royalties as owners of that particular sound recording. But when the same song plays on terrestrial radio, only Dolly gets paid for the performance.

Before 2018, digital platforms like Spotify and Apple Music were expected to locate every songwriter and pay them directly. The result was predictable chaos – and a wave of class actions for unpaid royalties. Congress responded with the Music Modernization Act (MMA), signed into law in 2018. Among its provisions was the creation of the Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC), a centralized database of musical works and their owners. Under the new system, digital streaming services like Spotify pay their mechanical royalties to the MLC, which then distributes them to registered songwriters and publishers.

Dolly Parton’s MMA registration of I Will Always Love You is here.

The MMA simplified life for the streaming platforms but shifted the burden of compliance to the creators themselves. If a songwriter fails to register with the MLC, they receive nothing – and cannot later sue for unpaid royalties. The law thus trades friction for finality, reinforcing the old rule of copyright: you can’t get paid for rights you can’t prove you own.

Modern Lessons: Taylor Swift and Peloton

Taylor Swift’s dispute with Big Machine Records shows how ownership of master recordings can become a flashpoint of creative control. Early in her career, Swift signed with Big Machine, which financed and owned the masters of her first six albums – a standard trade-off for a young artist. She retained her publishing rights as a songwriter, but not the recordings themselves. Years later, when Big Machine and its assets were sold to Ithaca Holdings, a company controlled by music executive Scooter Braun, Swift objected that she had been denied a fair chance to buy back her masters and that they were now controlled by someone she considered personally antagonistic. The sale meant that Braun’s group would profit from every use of her early recordings – streaming, licensing, or film placements – while she had no say in how they were used. Her response was to re-record those albums as Taylor’s Versions, creating new sound recordings she fully owns. Under copyright law, these re-recordings are distinct works that she can license freely, redirecting future revenue and fan loyalty to herself. The episode underscores the same principle Dolly Parton understood decades earlier: in music, ownership of copyright – especially the masters – remains the ultimate source of leverage and independence.

If Swift’s experience illustrates how artists can reclaim their rights through a deep understanding of copyright, Peloton’s experience shows what happens when companies overlook those rights. Peloton, the fitness company, was sued for using thousands of songs in workout videos without obtaining synchronization licenses from the publishers who owned the underlying compositions. The case settled quietly, but it exposed how easily digital platforms – even well-funded, sophisticated ones – can stumble over the invisible tripwires of copyright law.

A few years earlier, the fitness company Peloton learned a different lesson. It was sued for using thousands of songs in workout videos without securing synchronization licenses from the publishers. The case settled quietly, but it demonstrated how easily businesses operating in the digital realm can stumble over the invisible tripwires of copyright law.

Dolly’s Long Game

Half a century after she wrote I Will Always Love You, Dolly Parton continues to collect royalties from her composition in multiple ways. She, or her estate, will continue to earn these royalties until 2069, 95 years from first publication. Every radio spin, every concert, every cover version, every download, every stream, and every appearance in film or television generates a payment. Her insistence on retaining her publishing rights in the 1970s – long before “owning your masters” became a rallying cry – has made her one of the wealthiest and most respected figures in popular music. It is hard to imagine a more perfect example of how copyright literacy can translate into enduring creative and financial control.

Coda: Bowie’s Prediction Revisited

Bowie’s prediction that copyright would disappear within a decade now feels almost quaint. Yet he was right about one thing: digital technology transformed everything about how we experience music. What it didn’t destroy was the basic legal structure that allows artists to profit from their work. Copyright law, born in the age of sheet music and phonographs, has proved remarkably adaptable.

At its core remains a simple question – one that every lawyer, artist, and technologist must still answer:

Who owns the song?

by Lee Gesmer | Sep 1, 2025 | General

Update: the same day I posted this article Bartz and Anthropic announced that they had settled the case. The terms are as yet unknown, and the settlement will need to be approved by the judge. However, this topic is not moot – it could easily arise in one of the many genAI copyright cases still pending.

The eyes of the artificial intelligence community are laser-focused on the upcoming class action damages trial in Bartz v. Anthropic, scheduled for December 1, 2025. This will be the first GenAI copyright case to go to trial, and commentators have observed that the damages could exceed $1 billion. With dozens of similar cases pending this trial could foretell the future of many of those cases.

In the meantime, as the parties engage in the pre-trial struggle for advantages, a key issue has arisen: did Anthropic impliedly waive attorney-client privilege?

Background

On June 23, 2025 Judge William Alsup ruled that Anthropic’s use of copyright works to train its large language models (LLMs) is fair use. However, he also ruled that its downloading of protected works from so-called “shadow libraries” was not – those downloads were copyright infringement. Three weeks later he issued an order certifying a class of plaintiffs and scheduling a jury trial on statutory damages to begin on December 1, 2025. The class includes all owners of copyright-registered books in LibGen or PiLiMi, a number that could be in the millions. How many of the books downloaded were in-copyright and registered before Anthropic’s infringement commenced is an open question.

However, there will not be millions of trials – there will be one trial and the jury’s decision on statutory damages will apply to all members of the class. If the jury finds that Anthropic’s infringement was “willful” it could award damages as high as $150,000 per work infringed. If the jury finds the infringement was “innocent” damages could be as low as $200 per work. This measure of damages would apply to every member of the class – that is, to the owners of every book that was downloaded and which qualifies as a class member. If there is a dispute over a particular work (such as ownership, registration or whether the copyright has expired), it will be resolved by a Special Master appointedby the judge.

How the Attorney-Client Privilege Issue Arose

Like many defendants in copyright cases, early in the case Anthropic pleaded “innocent infringement” as an affirmative defense, reserving the right to argue that any infringement was in good faith and therefore deserving of minimal damages. On July 24, 2025 Judge Alsup, focused on this defense and issued an order requiring Anthropic to “show cause why its affirmative defense of innocent infringement should not be stricken unless it produces all evidence of advice of counsel.”

This order kicked off an as-yet unresolved battle over Anthropic’s right to argue innocent infringement while preserving attorney-client privilege.

Why It Matters

As noted above, the privilege fight goes directly to the amount of money the jury could award. In copyright cases, juries can award as little as $200 per work for “innocent” infringement or as much as $150,000 per work for “willful” infringement. What tips the scale is the infringer’s state of mind. If Anthropic’s lawyers warned that downloading from shadow libraries was unlawful and the company went ahead anyway, that looks like willful infringement and pushes damages toward the high end. If, on the other hand, counsel advised the practice was likely fair use, Anthropic can argue it acted on legal advice, and argue for damages at the bottom of the range. The plaintiffs want to pierce privilege because they suspect the hidden legal advice undermines Anthropic’s innocence claim; Anthropic is resisting because disclosure could hand plaintiffs exactly what they need to prove willfulness.

The Arguments on Each Side

Anthropic responded to the judge’s show cause order by stating that it has not invoked an “advice of counsel” defense and has no intention of doing so. It relies on Ninth Circuit precedent for the proposition that implied waiver occurs “only when the client tenders an issue touching directly upon the substance of an attorney-client communication.” In Anthropic’s telling, its witnesses will testify based on their industry experience and objective evidence – not on what the lawyers told them. Privilege, the company argues, doesn’t vanish just because lawyers were consulted along the way. Anthropic points to the testimony of its co-founder, Benjamin Mann, who has testified that, based on his prior experience at OpenAI, he believed that downloading from a shadow library (specifically, LibGen) for LLM training was fair use.

The book-author class plaintiffs responded that if Anthropic intends to assert that its infringement was “innocent,” shouldn’t the jury hear what Anthropic’s lawyers told it? The author-plaintiffs argue that Anthropic’s assertion of “innocent infringement” and its denial of willfulness puts its lawyers’ advice squarely in issue.

Plaintiffs note that Anthropic’s witnesses, when asked about the legality of downloading books from shadow libraries, repeatedly invoked privilege. That, plaintiffs say, shows that counsel’s advice played “a significant role in formulating [their] subjective beliefs”. Having chosen to defend its conduct as “innocent,” plaintiffs argue, Anthropic cannot now shield the very communications that shaped its beliefs.

Who Has The Better Argument?

Based on the arguments of both parties and the cases cited, I give the edge to Anthropic. Anthropic says it won’t rely on advice of counsel and will ground “innocent infringement” in industry practice/experience, not lawyer communications. That fits the dominant Ninth Circuit approach that implied waiver requires affirmative reliance on privileged advice, not mere relevance of state of mind. Although Judge Alsup raised the issue, I think it’s likely that he will back off and rule in favor of Anthropic on the implied waiver issue.

However, Anthropic will need to exercise extreme care at trial – the advantage can flip fast if a witness “opens the door” to a privileged communication (for example, testifies that “legal cleared it”) or if plaintiffs develop a clear link between subjective belief and counsel’s advice. If that happens, expect Judge Alsup to either compel production, preclude the “innocent” narrative, or strike the defense altogether on fairness grounds.

What To Watch Next

Judge Alsup now faces the question of whether Anthropic can walk the tightrope – denying willfulness and pressing an innocent infringement defense while keeping its lawyers’ advice behind the curtain of privilege. A hearing on this issue is scheduled for August 28, 2025. If the court rules against Anthropic, it may be forced to choose between disclosing lawyer communications or dropping the innocence defense, in which case the judge is likely to instruct the jury that the floor for damages is $750 per work (the floor for non-innocent or “ordinary” infringement), rather than $200. And, of course, without an innocence defense damages could climb much higher – as high as $150,000 per work infringed.

In the meantime, this case could come to a sudden halt: Anthropic has filed an emergency motion with the Ninth Circuit, asking it to stay the case pending its appeal of Judge Alsup’s class certification order.

Stay tuned.

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 5, 2025 | Copyright

The United States is in a race to achieve global dominance in artificial intelligence (AI). Whoever has the largest AI ecosystem will set global AI standards and reap broad economic and military benefits. Just like we won the space race, it is imperative that the United States and its allies win this race. . . . Build, Baby, Build. America’s AI Action Plan, July 2025

The explosion of generative AI has triggered a legal crisis that few saw coming and nobody seems equipped to fix. At the center is a deceptively simple question: Can companies train AI models on copyrighted material without permission?

The stakes are enormous. This isn’t just about Big Tech and copyright holders duking it out. It’s about the future of the creative economy, the limits of fair use, and whether the U.S. legal system can adapt fast enough to regulate technologies that don’t wait for case law to catch up.

So far, there’s no clear direction. The White House is all-in on open access. Some in Congress want to prosecute. And the federal courts? Let’s just say consensus is not the word that comes to mind.

The White House: “You Just Can’t Pay for Everything”

On July 23, 2025, President Trump released his administration’s AI Action Plan, a blueprint for building a domestic AI ecosystem strong enough to beat China in the AI race. And in classic Trump fashion, he skipped the legalese and went straight to the point:

the AI race. And in classic Trump fashion, he skipped the legalese and went straight to the point:

“You can’t be expected to have a successful AI program when every single article, book, or anything else that you’ve read or studied, you’re supposed to pay for. … When a person reads a book or an article, you’ve gained great knowledge. That does not mean that you’re violating copyright laws or have to make deals with every content provider. … You cannot expect to every single time say, ‘Oh, let’s pay this one that much. Let’s pay this one.’ Just doesn’t work that way.”

Trump didn’t say “fair use,” but he didn’t need to. The message was clear: licensing everything is a non-starter, and AI should be free to learn from copyrighted works without paying for the privilege. Whether that’s a legal position or just a policy stance is beside the point. Either way, the administration is betting that a permissive approach is the price of staying ahead in the global AI race.

Congress: “The Largest IP Theft in American History”

On Capitol Hill, the mood is very different. Just one week earlier, on July 16, the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Crime and Counterterrorism held a hearing titled Too Big to Prosecute? Examining the AI Industry’s Mass Ingestion of Copyrighted Works for AI Training.

held a hearing titled Too Big to Prosecute? Examining the AI Industry’s Mass Ingestion of Copyrighted Works for AI Training.

Senator Josh Hawley opened the hearing with a blunt accusation:

“Today’s hearing is about the largest intellectual property theft in American history … AI companies are training their models on stolen material. Period. We’re talking about piracy. We’re talking about theft. This is not just aggressive business tactics. This is criminal conduct.”

He went on to ridicule national security arguments as thin cover for profiteering:

“Every time they say things like ‘We can’t let China beat us.’ Let me just translate that for you. What they’re really saying is ‘Give us truckloads of cash and let us steal everything from you and make billions of dollars on it.’”

While Congress remains divided on the issue, Hawley’s remarks reflect just how far the rhetoric has escalated – and how close it is coming to framing AI training not as a policy problem, but as a prosecutable offense. Hawley has teamed up with Senator Blumenthal on a bipartisan bill that would prohibit AI companies from training on copyrighted works without permission.

The Courts: No Consensus, No Clarity

Meanwhile, the federal courts have offered no consistent theory of their own. As I’ve noted before, two judges in the Northern District of California – William Alsup and Vince Chhabria – have reached diametrically opposed conclusions on both AI training and the legality of acquiring training data from pirate sites.

In Bartz v. Anthropic Judge Alsup ruled that using copyrighted works to train LLMs is “highly transformative” and likely protected by fair use. At the same time, he found that downloading copyrighted books from pirate sites for this purpose is plainly unlawful. Consequently, Anthropic now faces potentially massive class action liability.

In Kadrey v. Meta Judge Chhabria more or less flipped that script. He expressed serious doubt that AI training is fair use – but still ruled in Meta’s favor. Why? Because the plaintiffs (a group of well-known authors) failed to show that Meta’s use harmed the market for their books. And on the question of downloading books from pirate sites? Chhabria said it might be fair use after all – at least in this context.

So not only do two judges disagree on whether training is lawful – they also can’t agree on whether using pirated copies is legal.

Conclusion: Law Unmade

The legal framework surrounding AI training is collapsing under the weight of its contradictions. The executive branch supports open access. Congress calls it theft. The courts can’t agree on what the law is, let alone how it should evolve. And this isn’t theoretical: almost 50 copyright cases involving generative AI are now pending in U.S. courts, and the legality or illegality of using copyrighted content to train models could have a profound effect on the entire industry.

In this vacuum, AI companies continue to train their models. Copyright owners continue to sue. Policymakers continue to hedge. And the public is left wondering whether copyright law is still capable of responding to technological change.

This uncertainty is more than academic. It chills investment, clouds business models, and puts AI companies in the impossible position of defending their work without clear legal boundaries. Without guidance from Congress or a unifying appellate decision, generative AI will remain stuck in legal limbo – and in that limbo, the line between innovation and infringement will only grow harder to draw.