When the Massachusetts Noncompetition Agreement Act (MNAA) took effect in October 2018, I described the law in detail and wrote that employers and employees were entering “a new era” in noncompete law. The statute imposed formalities, created new employee protections, and limited the enforceable duration of noncompetes. But it also drew a set of carefully worded exclusions – most notably for nonsolicitation agreements. I predicted that those exclusions would become critical as employers adjusted to this new law.

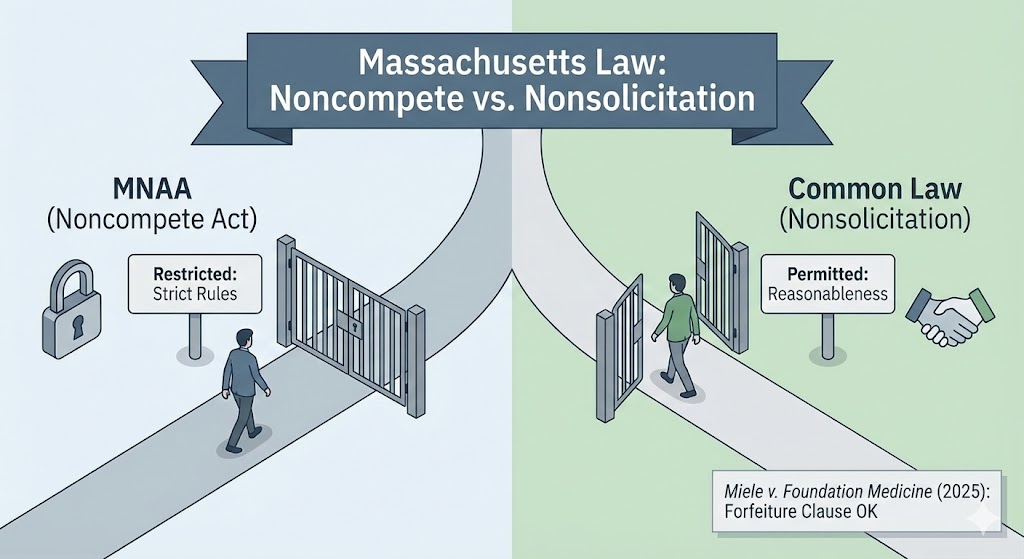

Seven years later, the Supreme Judicial Court has now decided its first significant case interpreting the statute, Miele v. Foundation Medicine, Inc. (2025). The decision answers a narrow question, but it carries substantial practical consequences. The court held that the MNAA does not apply when an employer conditions severance pay on compliance with an employee-nonsolicitation covenant. In other words, adding a forfeiture-of-benefits clause to a nonsolicit does not convert it into a noncompetition agreement.

What the MNAA Regulates – And What It Doesn’t

The MNAA regulates agreements that bar a former employee from engaging in post-employment competition. To be enforceable, such agreements must satisfy a gauntlet of statutory onerous requirements: advance notice, a written agreement signed by both parties, the right to consult counsel, a one-year limit on duration (with narrow exceptions), and “garden leave” or other agreed-upon consideration.

And, importantly, the MNAA includes “forfeiture for competition” agreements under the definition of noncompetition agreements. This was designed to prevent employers from avoiding the statute’s requirements by replacing a noncompete with a compensation-forfeiture clause that accomplishes the same result. In other words, employers should not be able to sidestep limits on noncompetes by changing the mechanism of enforcement.

The statute is sufficiently burdensome that employee noncompete agreements, once a routine feature of employment contracts in Massachusetts, are now seldom used.

But the statute does not sweep in every type of restrictive covenant. Its definition of “noncompetition agreement” excludes several categories, including:

- Employee and customer nonsolicitation covenants

- Confidentiality and intellectual-property assignment provisions

- Covenants linked to the sale of a business

As I noted in 2018, those exclusions matter. A well-drafted nonsolicitation clause can serve much of the protective function that noncompetes historically played. The MNAA left those covenants to be governed by common-law reasonableness standards rather than the statute’s rigid framework.

The Dispute in Miele

Susan Miele signed an employee-nonsolicitation agreement when she joined Foundation Medicine in 2017. When she left the company in 2020, she entered into a “transition agreement” providing substantial severance benefits. That agreement incorporated the earlier nonsolicitation covenant and added a forfeiture clause: if she breached any of her continuing obligations, she would forfeit unpaid benefits and repay benefits already received.

After Miele joined a competitor, Foundation Medicine alleged that she solicited several FMI employees during the one-year restricted period. The company stopped payments and demanded repayment. Miele sued, arguing that the forfeiture provision was an unenforceable “forfeiture for competition” agreement subject to the MNAA.

She took this argument all the way to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and lost.

The SJC’s Holding: A Nonsolicitation Clause Remains a Nonsolicitation Clause

The SJC’s analysis turned on the statute’s definitions. The MNAA:

- Excludes nonsolicitation agreements from the category of noncompetition agreements; and

- Defines forfeiture-for-competition agreements as a type of noncompetition agreement.

Given those two premises, the court held that a forfeiture triggered by a breach of a nonsolicitation covenant is not a “forfeiture for competition agreement” under the MNAA. The forbidden conduct was solicitation, not competition itself. Because the underlying covenant falls outside the statute, the forfeiture remedy does not bring it back within the statute’s scope.

In short: the presence of a forfeiture provision does not change the legal identity of the underlying restrictive covenant. If the covenant is a nonsolicitation clause, the MNAA does not apply.

Implications Going Forward

Miele gives employers and employees much-needed clarity, and it confirms several practical realities about the MNAA:

- Nonsolicitation provisions remain outside the statute, even when backed by serious financial consequences. A severance agreement that conditions payment on compliance with a nonsolicitation covenant does not trigger the MNAA merely because the remedy is forfeiture or repayment. These provisions will continue to be governed by pre-2018 common law.

- The MNAA’s reach depends on the nature of the restricted activity, not the chosen remedy. If an agreement penalizes an employee for working for a competitor, it is a forfeiture-for-competition agreement subject to the statute. If it penalizes solicitation, it is not. The drafting focus rests on the conduct being restricted, not the mechanism of enforcement.

- Common-law reasonableness remains the governing framework for nonsolicitation covenants. Duration, scope, legitimate business interest, and employee role still matter. Parties should expect future litigation over what counts as “solicitation,” a concept the common law has never cleanly defined. I wrote about this perplexing topic more than ten years ago in Nudge, Nudge, Wink, Wink – Are You “Soliciting” in Violation of an Employee Non-Solicitation Agreement?

- Separate statutes still matter. Miele does not insulate forfeiture clauses from scrutiny under the Massachusetts Wage Act or other employment statutes. Severance structured as earned compensation, for example, may present Wage Act issues if subject to forfeiture.

- Expect heavier reliance on nonsolicitation + severance-forfeiture structures. The decision validates a drafting strategy employers began adopting after 2018: use narrower covenants that avoid the MNAA altogether, coupled with meaningful financial incentives for compliance.

Conclusion

When the MNAA was enacted, the open question was how far courts would go in applying its protective rules beyond traditional noncompetes. Miele provides a clear boundary: the MNAA governs restraints on competitive employment, not every restrictive covenant that may influence post-employment behavior. Nonsolicitation clauses, even with substantial economic consequences attached, remain on the common-law side of the line.

Employers will undoubtedly make fuller use of that space. Employees and their counsel will scrutinize whether a provision labeled “nonsolicitation” is in substance a broader restriction. And the statute will continue to generate interpretive questions as parties test its edges.