by Lee Gesmer | Sep 3, 2022 | Copyright

With some exceptions, every public venue that plays popular music for its customers – concert venue, bar, restaurant, shopping mall or health club – needs to enter into a blanket license agreement with ASCAP, BMI and SESAC, the performing rights organizations (PROs) that pay public performance royalties to songwriters and publishers.

Occasionally a club will fail to join a PRO, ignore warnings and be sued for copyright infringement.

Here’s a current example in which a club did sign a license with ASCAP, but allegedly failed to pay ASCAP the license fees.

Universal Music v. Calvin Theater

Two music publishers have sued Calvin Theater and its owner/manager, Eric Suher, for violating public performance rights in six compositions. Calvin Theater is a music venue in Northampton, Massachusetts, and the suit was filed in the Federal District Court for the District of Massachusetts. ASCAP manages the public performance rights for these songs.

District of Massachusetts. ASCAP manages the public performance rights for these songs.

We don’t know why Calvin Theater failed to pay ASCAP. However, the publishers’ claim is that because the venue is in breach the agreement is not in effect and the Theater has no copyright license.

Based on the allegations in the complaint this case is a good opportunity to do a short tutorial on the intersection of the music industry and copyright law.

The Infringement Involves “Musical Compositions,” Not “Sound Recordings”

Every musical work can have two copyrights – the musical composition (melody, lyrics) and the sound recording. The owners can be different, and usually are – it’s common for a record company to own the copyright in the “master” sound recording and a publishing company to own rights in the musical composition.

Calvin Theater involves the public performance of musical compositions – there is no allegation that sound recordings were illegally copied. The complaint doesn’t identify the owner of the sound recordings, nor does it need to do so.

The complaint doesn’t provide any detail about how the compositions were performed. Were the works performed by a live band? Did the Calvin Theater play a CD or stream the songs? Were the songs played over a radio? Which versions of the songs were played – the originals or cover recordings? The complaint doesn’t tell us, but it doesn’t matter – regardless of how the songs were played, the owners of the copyrights in the musical compositions are entitled to a public performance royalty. The music club should have paid that through a contract with ASCAP.

What Is The Right of Public Performance?

One of the exclusive rights held by owners of musical compositions is the right to publicly perform a work. The Copyright Act defines public performance broadly – “to perform … at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered.”

If a public venue plays popular music for its customers, it needs a public performance license. If it plays music and doesn’t have one, it’s a copyright infringer.

If you’re wondering about the public performance rights of owners of sound recordings – they don’t have one, except for digital audio transmissions. 17 U.S. Code § 106

What Are Publishing Companies?

The plaintiffs in this case are publishing companies. What’s that, you ask?

A lot of composers don’t have the time or inclination to deal with the music business. Instead, they assign ownership of their compositions to a publishing company to manage. There are many publishing companies, and the largest own publishing rights to thousands of songs. Two large publishers are the two plaintiffs in this case – Universal Music Publishing and Primary Wave.

to a publishing company to manage. There are many publishing companies, and the largest own publishing rights to thousands of songs. Two large publishers are the two plaintiffs in this case – Universal Music Publishing and Primary Wave.

What Are Performing Rights Organizations?

The owners of compositions – whether publishing companies or the composers themselves – can’t track and police the thousands of public venues where their compositions may be performed. A complex system has evolved to deal with this – they register their compositions with one of the PROs – ASCAP, BMI or SESAC. In turn, the PROs enter into blanket license agreements with the clubs and restaurants.

The clubs pay the PROs, the PROs pay the publishing companies, and the publishing companies pay the composers. This is all regulated by contracts – thousands and thousands of contracts.

It’s even more complicated than it sounds. For a deeper dive see Songtrust’s “Modern Guide to Music Publishing.“

The Publishing Companies Are Assignees of the Publishing Rights

The two plaintiffs in this case allege that they are owners of the six compositions that have been infringed. From this we know that the composers have transferred ownership of the compositions to these companies. The publishers must be either owners or exclusive licensees to bring a copyright infringement lawsuit.

to bring a copyright infringement lawsuit.

Both publishers are members of ASCAP. In order to avoid infringing the compositions of these songs, Calvin Theater needed to enter into a blanket license agreement with ASCAP and not breach the agreement.

The Owner of the Club May be Personally Liable

The complaint alleges that Eric Suher is an owner, officer and director of Calvin Theater, that he controls, manages and operates the company that owns the club, and that he has the right and ability to supervise and control the public performance of musical compositions at the club.

This is important – in my experience many lawyers and business owners don’t realize that a corporation may not shield a business owner or manager from personal liability for copyright infringement. For details on why this may be the case, see Redigi – Did Ossenmacher Know He Was Risking Personal Liability?

If the publishers win their case Suher and Calvin Theater may be jointly and severally liable for copyright infringement.

The Works Are Registered

To bring a claim of copyright infringement a work must be registered. This was uncertain until 2019, when the Supreme Court decided Fourth Estate Public Benefit Corp. v. Wall-Street.com, LLC. Before that some courts held that a pending registration was sufficient.

Here the publishers provided the registration numbers and dates for each registration. The compositions were initially registered in the early/mid-1970s. None of the copyrights have expired. In fact, the composers are still alive, so the copyrights will remain in effect for at least another 70 years. Even though the copyrights have been transferred, their duration continues to follow the lives of the composers.

early/mid-1970s. None of the copyrights have expired. In fact, the composers are still alive, so the copyrights will remain in effect for at least another 70 years. Even though the copyrights have been transferred, their duration continues to follow the lives of the composers.

The Publishers Are Seeking Statutory Damages

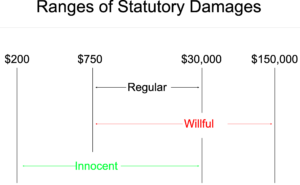

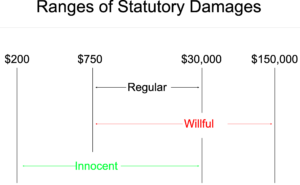

The publishers don’t want actual damages (their lost profits) or the club’s profits attributable to the infringement – these are probably minimal. The publishers have asked for statutory damages of between $750 and $30,000 per infringing work.

Because the registrations preceded the infringements (which took place in 2022), they are entitled to seek statutory damages and, at the discretion of the judge, attorney’s fees.

However, the amount they are seeking is worth questioning – when an infringement is “willful” statutory damages may be as high as $150,000 per work infringed – in this case that would total $900,000. The publishers allege that ASCAP repeatedly told Calvin Theater that it was infringing and demanded that the Theater pay the contractual license fees. It’s not clear why the publishers are not seeking $150,000 per work based on what appears, at least for pleading purposes, to have been willful infringement.

That said, statutory damages are complicated. This table illustrates the options, depending on whether an infringement is “innocent,” “regular” or “willful”:

Conclusion

If the allegations are true this is a straightforward case. It illustrates the elements of a copyright case in the music industry, and how much trouble a public venue can get into by ignoring the requirement that it license rights from the performing rights organizations if it’s going to play popular music.

However, music publishers are not in business to force music venues into bankruptcy. Most likely Calvin Theater’s lawyers will tell their client that it should settle, and the publishers will accept reasonable terms. I’ll keep an eye on the case and update this post if that happens.

Update: The case was dismissed in December 2022. Very likely the dismissal was pursuant to a settlement.

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 22, 2022 | Copyright

The doctrine of fair use has been called, with some justification, the most troublesome in the whole law of copyright. Justice Blackmun. Sony v. Universal (1984)

Fair use in America simply means the right to hire a lawyer. Larry Lessig

Fair use is the great white whale of American copyright law. Enthralling, enigmatic, protean, it endlessly fascinates us even as it defeats our every attempt to subdue it. Prof. Paul Goldstein

*********

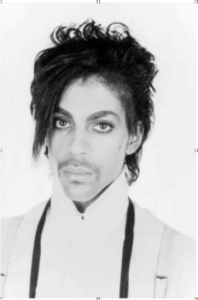

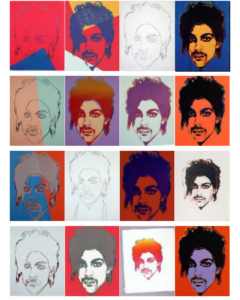

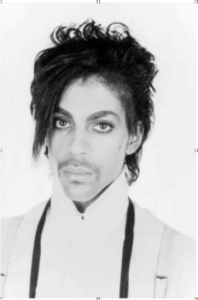

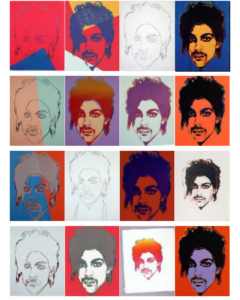

The photo of Prince directly below was taken by Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. Andy Warhol used this photo to create an unauthorized series of sixteen silkscreens and drawings – the “Prince Series” – which appears below Goldsmith’s photo.

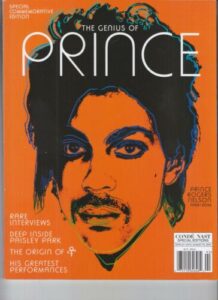

Conde Nast Cover

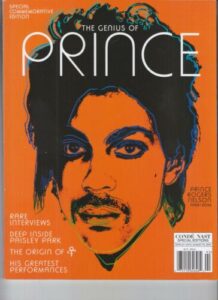

Goldsmith is a well-known rock-and-roll celebrity photographer. When Warhol passed away in 1987 the Prince Series became the property of the Warhol Foundation. Goldsmith was unaware of its existence until Condé Nast licensed one of the silkscreens for the cover of a Prince tribute magazine following Prince’s death in 2016. When Goldsmith learned that Warhol had copied her photo she sued the Warhol Foundation for copyright infringement.

Warhol’s defense in Goldsmith’s case is fair use – specifically the “transformative” branch of copyright fair use. This has its origin in Campbell v. Accuf-Rose, a 1994 case involving a parody of Roy Orbison’s song “Pretty Woman.” The Supreme Court held that a new work of art is “transformative” for purposes of copyright fair use if it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.”

This legal standard has proven to be subjective and inconsistent in its application. The Warhol case is a good example.

The District Court and Second Circuit Decisions in Warhol

A Southern District of New York district court judge agreed with Warhol’s defense that the Prince Series was “transformative.” The judge reasoned that while Goldsmith’s photo portrays Prince as “not a comfortable person” and a “vulnerable human being,” the Prince Series portrays the musician as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.” Comparing the works side-by-side, the district court concluded that a reasonable observer would perceive that Warhol’s work has a “different character, a new expression, and employs new aesthetics with [distinct] creative and communicative results” when compared to the Goldsmith original.

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed. It held that to satisfy the “transformative” requirement the second work (the Warhol Series) must –

. . . at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work such that the secondary work remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material. The judge must examine whether the secondary work’s use of its source material is in service of a fundamentally different and new artistic purpose and character, such that the secondary work stands apart from the raw material used to create it.

In the eyes of the Second Circuit Warhol’s silkscreens failed this test. Hence, they were not protected by fair use.

Interest in the case has been high since the Second Circuit issued its decision last year. It increased when the Supreme Court agreed to hear Warhol’s appeal, and has gone into overdrive as the case approaches oral argument on October 12, 2022. Warhol filed its appeal brief in early June. Goldsmith filed her opposition in early August. More than 30 amicus briefs have been filed. The Copyright Office and the Solicitor General have filed an amicus brief in support of Goldsmith, and the Solicitor General has asked for leave to participate at oral argument.

Google v. Oracle: Will It Matter to the Warhol Appeal?

An important consideration is how the Court’s 2021 ruling in Google v. Oracle may impact this case. Google is only the second time the Supreme Court has addressed fair use in depth. However, while the Court upheld Google’s fair use defense, the subject of that case was far from the traditional core of copyright – visual art, music and writings. Google involved fair use in the context of Google’s copying and reimplementation of Oracle’s Java API user interface. The Court found this to be fair use because it was socially beneficial – it allowed programmers familiar with the Java API to use their knowledge and experience to program Google’s Android operating system, rather than having to learn a new API. See Final Thoughts On Google v. Oracle.

Warhol argued that Google helped tip the scales in its favor, but the Second Circuit rejected this argument, stating that “a case that addresses fair use in such a novel and unusual context [as functional computer programs] is unlikely to work a dramatic change in the analysis of established principles as applied to a traditional area of copyrighted artistic expression.”

Will the Supreme Court affirm or reverse the Second Circuit? Setting aside Google (which is something of a one-off for copyright fair use), this is only the second time the Court will have addressed fair use since 1994 – will the Court expand fair use (by reversing the Second Circuit), contract it or tread lightly and leave it largely intact?

In pondering these questions it’s worth noting that changes in the Court’s make-up may be a significant factor in the outcome of this case.

Fair Use at the Supreme Court Without Justice Breyer

Until his retirement in June 2022 Justice Breyer had focused on intellectual property law more than any other member of the Court. He was viewed as the most liberal justice on IP issues, and he wrote the majority pro-fair use decision in Google.

Given the current make-up of the Court post-Breyer, a little armchair kremlinology is in order.

Based on their dissent in Google it seems likely that Justices Thomas and Alito will vote to uphold the Second Circuit’s decision for Goldsmith. Under their view of fair use the most important factor is the effect of Warhol’s silkscreens on the market for Goldsmith’s photo. (Google, p. 1216). The Second Circuit found that Warhol’s silkscreens negatively impacted the market for Goldsmith’s original photo in a variety of ways, and Justices Thomas and Alito are likely to overweight this factor in concluding that Warhol’s silkscreens are not protected by fair use.

The remaining justices on the new “conservative” wing of the Court – Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett – favor “textualism,” the judicial philosophy that places primary weight on the normal meanings of a statute’s words, rather than public policy. It’s worth noting that the word “transformative” (indeed, the concept) appears nowhere in the Copyright Act, and is something of a judicial gloss on the statutory enumerated fair use factors. Based on a strict application of textualism these three justices may side with Justice Thomas’s view of fair use, in which case the Warhol Foundation will lose its bid to reverse the Second Circuit 5-4. If “swing conservative” Chief Justice Roberts joins the conservative wing, Warhol will lose at least 6-3.

My prediction: the Second Circuit’s ruling in favor of Lynn Goldsmith will be affirmed by at least a 5-4 vote.

Conclusion

Either way, affirm or reverse, will this case change fair use in the U.S.? We won’t know until the Supreme Court issues its decision, likely sometime in 2023. In the meantime, tune in to the oral argument in October and judge for yourself.

Update 5-18-23: I was correct in predicting that the Court would uphold the Second Circuit in this case. Here is the 7-2 decision – link

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 24, 2022 | CFAA

One of the enduring mysteries of Internet law is the legality of “web scraping.” Although scraping is invisible to most users it pervades the Internet and constitutes a substantial volume of all Internet traffic.

Here are two examples of scraping: (1) Clearview AI has scraped billions of publicly available images from social media platforms and compiled them into a facial recognition database that it’s made available to law-enforcement and private industry. (2) hiQ Labs has scraped publicly available information from profiles on LinkedIn and used it to analyze and predict employees’ likelihood of seeking other employment

Both of these companies engaged in web scraping without permission. Did either of them violate any laws? This post will examine how the courts have treated hiQ’s actions, but the broader context, beyond that case, is that web scraping often is a legal enigma. As one commentator noted, “most often the legal status of scraping is characterized as something just shy of unknowable, or a matter entirely left to the whims of courts …. .” Sellars, Twenty Years of Web Scraping and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, p. 377 (link).

Web Scraping

But first, what is web scraping? Here’s a definition provided by the Electronic Frontier Foundation: “web scraping is machine-automated web browsing that accesses and records the same information which a human visitor to the site might do manually.” Typically this function, also called data scraping, is performed by an Internet bot, or simply “bot,” a software program that runs automated tasks (scripts) over the Internet. A well-known example of this is Google, which uses its web scraper, “Googlebot,” to collect data from the Internet that is then indexed for searching via Google’s Internet search software.

Internet scraping is often done without the permission of the people and companies that post information on websites. Courts and legal commentators have identified many legal claims that an aggrieved party might assert against scrapers. These include trespass to chattels, copyright infringement, misappropriation, unjust enrichment, conversion, breach of contract and breach of privacy. See Sobel, A New Common Law of Web Scraping (link).

Most of these claims remain theoretical and untested in the courts. However, there is one law that has been used successfully to challenge scraping – the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 18 U.S. Code §1030, or the “CFAA.” (link)

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

The CFAA – the federal anti-hacking law – imposes civil and criminal liability for certain acts of computer trespass. The hiQ/LinkedIn case focused on the CFAA’s “without authorization” provision. This section of the law imposes liability on ”[w]hoever … intentionally accesses a computer without authorization … and thereby obtains … information ….”

The CFAA applies to any computer connected to the Internet. Therefore, the CFAA may be violated when someone accesses a website “without authorization.” However, the words “without authorization” are undefined, leaving it to the courts to decide how they should be applied.

What if a company scrapes data from a website that has required it to agree to contractual terms and conditions that bar scraping? In this case it may have acted “without authorization” and therefore violated the CFAA. At the very least, it will be in breach of contract.

But what if the website is public facing – that is, it makes information available to visitors without the use of a password – and the site owner demands that it stop? Are the scraper’s actions now “without authorization”? That was the issue the Ninth Circuit recently decided in hiQ Labs, Inc. v. LinkedIn Corp. (9th Cir. April 18, 2022).

hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn Corp.

hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn has an unusual legal posture and complex history spanning five years. hiQ, a corporate data analytics company, uses automated software to collect information that LinkedIn users share on their public profiles. LinkedIn.com is a public facing website whose users own the information they provide to LinkedIn. LinkedIn tried to stymie hiQ with IP blocking, but this proved unsuccessful. LinkedIn then demanded that hiQ stop scraping its site, asserting that it violated the CFAA. After receiving this demand hiQ filed suit on the theory of tortious interference, seeking a declaratory judgment that LinkedIn could not lawfully invoke the CFAA or use technological measures to stop it from scraping LinkedIn.com.

hiQ scored an initial victory before the district court – the court issued a preliminary injunction ordering LinkedIn to withdraw its cease-and-desist letter and remove any existing technical barriers to hiQ’s access to public profiles.

LinkedIn appealed, leading to a decision by the Ninth Circuit, a Supreme Court appeal and remand (remanded in light of Van Buren, below, without opinion), and a second decision by the Ninth Circuit. At all times during this convoluted procedural history the central question was whether, once LinkedIn demanded that hiQ cease scraping the site, any further scraping of LinkedIn’s data was “without authorization” in violation of the CFAA. Simply put, once LinkedIn demanded that hiQ stop scraping did hiQ violate the CFAA by failing to comply?

After much discussion, including analysis of the wording of the statute, case precedents and the legislative history, the Ninth Circuit upheld the preliminary injunction in hiQ’s favor, stating –

the CFAA’s prohibition on accessing a computer “without authorization” is violated when a person circumvents a computer’s generally applicable rules regarding access permissions, such as username and password requirements, to gain access to a computer. It is likely that when a computer network generally permits public access to its data, a user’s accessing that publicly available data will not constitute access without authorization under the CFAA. The data hiQ seeks to access … has not been demarcated by LinkedIn as private using … an authorization system. hiQ has therefore raised serious questions about whether LinkedIn may invoke the CFAA to preempt hiQ’s possibly meritorious tortious interference claim.

The court referenced the “gates-up-or-down” inquiry that the Supreme Court established in Van Buren v. United States (USSC 2021), which involved the “exceeds authorized access” prong of the CFAA (not at issue in LinkedIn):

In other words, applying the ‘gates’ analogy to a computer hosting publicly available webpages, that computer has erected no gates to lift or lower in the first place. Van Buren therefore reinforces our conclusion that the concept of ‘without authorization’ does not apply to public websites.

And, the court touched on an antitrust-flavored policy rationale that supported hiQ’s access:

. . . the public interest favors hiQ’s position. . . . giving companies like LinkedIn free rein to decide, on any basis, who can collect and use data—data that the companies do not own, that they otherwise make publicly available to viewers, and that the companies themselves collect and use—risks the possible creation of information monopolies that would disserve the public interest.

Based on this reasoning the Ninth Circuit refused to dissolve the preliminary injunction against LinkedIn, sending the case back to the district court for further proceedings.

Implications

What does the decision mean for data aggregators and researchers who use bots to “scrape” information from public facing websites? With some qualifications it is a win for both non-profit researchers and for-profit companies like hiQ and Clearview AI, who seek to scrape and exploit data commercially. Under this decision a public facing, “gates up” website cannot use the CFAA to demand that a scraper stop.

However, there are limits. For example, aggregators need to be careful not to copy expression that may be protected by copyright. That was not an issue in the LinkedIn case, since users retain ownership of their profiles, and therefore LinkedIn has no copyright interest in the data contributed by its users.

The ruling creates an incentive for websites to shield information behind a log-in page and terms and conditions barring data scraping, although whether this constitutes a violation of the CFAA in every instance remains uncertain.

State law causes of action, particularly common law trespass to chattels, are an undeveloped but possibly viable theory for websites seeking to block scraping. The Ninth Circuit called this out specifically: ”it may be that web scraping exceeding the scope of the website owner’s consent gives rise to a common law tort claim for trespass to chattel.” Whether this theory will hold water remains to be seen. In the meantime, idiosyncratic state laws may come into play. Clearview AI – the company that created a facial recognition database – has been targeted for violation of the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act. (link)

Lastly, the Ninth Circuit is only one of many federal circuits, and other circuits may disagree with the conclusion reached in this decision. The day may come when the Supreme Court decides the legality of web scraping of public facing data under the CFAA. LinkedIn v. hiQ is ongoing, and perhaps this very case will end up back before the Supreme Court.

A Postscript on Technical Barriers

Any discussion of this case would remain incomplete without a mention of the technical barriers issue. Recall that the trial court ordered LinkedIn to remove any existing technical barriers to hiQ’s access to public profiles. Specifically, the trial court entered a preliminary injunction enjoining LinkedIn from “blocking or putting in place any [technical] mechanism with the effect of blocking hiQ’s access to LinkedIn member public profiles.” This included IP address blocking, which LinkedIn had attempted before the lawsuit began. The trial court entered this order based on the doctrines of tortious interference and unfair competition.

This order was upheld by the Ninth Circuit on both appeals.

If this aspect of the case has you puzzled you are not alone. If you are a technologist you may be wondering why, even if LinkedIn didn’t have a CFAA claim against hiQ, it should be unable to take efforts to attempt to block hiQ from accessing its site. If you’re a lawyer, you know that claims of tortious interference and unfair competition are difficult to maintain, and you may be wondering how LinkedIn’s IP blocking could be a violation of either doctrine.

None of the courts that have issued rulings in this case have addressed these issues, other than in passing.

Now that the case is back in the district court this aspect of the case – which should be of ongoing interest to both the technical and legal Internet communities – will likely receive further attention.

LinkedIn v. hiQ (9th Cir. Apri 18, 2022)

by Lee Gesmer | Apr 27, 2022 | Copyright

If you own or manage a website you may be familiar with the process of “photo embedding” or “inline linking” an image or video on your site. Rather than hosting the image file on your own server you retrieve the image from another Internet site and embed the content as part of your webpage’s overall display. Users can’t tell the difference, but as a technical (and legal) matter you never “copy” the image to your server.

This practice is common, and has been performed millions of times on millions of sites. You have no legal concerns since you’re just channeling the image from another site. No worries, right?

Not so fast. This is actually a hotly disputed legal issue in the world of digital copyright.

For many years there actually were no worries. Way back in 2007 the Ninth Circuit created what has come to be called the “server test” in Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc. This gave unauthorized embedding a legal green light so long as the image resided on another server. In copyright lingo the embedding site does not host any “material objects … in which a work is fixed … and from which the work can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated” and thus does not communicate a copy. 17 U.S.C. § 101.

However, in addition to the right of reproduction the Copyright Act gives the owner of a work the right of public display – copyright owners have the exclusive right to “transmit or otherwise communicate… a display of the work… to the public, by means of any device or process.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. The Ninth Circuit used similar reasoning to hold that an image is not displayed when the embedding site’s computer does not store the photographic images.

For many years the “server test” has been shaky but accepted law. A few courts around the country suggested that the Ninth Circuit’s holding that unauthorized embedding didn’t constitute public display was questionable, but there were no clear rulings on this issue.

However, in the recent decision in McGucken v. Newsweek LLC (S.D. N.Y. March 21, 2022) a federal district court in the southern district of New York (the “SDNY”) outright rejected this rule in a case in which Newsweek embedded a photographer’s Instagram post in an online news article without his permission. The court focused on the right of display and concluded that –

After all, the Copyright Act defines “display” as “to show a copy of” a work, 17 U.S.C. § 101, and not “to make and then show a copy of the copyrighted work.” . . . The Ninth Circuit’s approach, under which no display is possible unless the alleged infringer has also stored a copy of the work on the infringer’s computer, would seem to make the display right merely a subset of the reproduction right. . . . The Copyright Act makes clear, however, that to “show a copy” is to display it. . . . Therefore, the Court finds that Defendant did in fact display Plaintiff’s Photograph when it embedded the Photograph in the Article.

In fact, this is the second time an SDNY court has reached this conclusion. In Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, LLC (2018) the district court held that an embedded tweet violated the photographer-plaintiff’s right of public display: “the plain language of the Copyright Act . . . provides no basis for a rule that allows the physical location or possession of an image to determine who may or may not have ‘displayed’ a work within the meaning of the Copyright Act.” (See my earlier post, Is In-Line Linking Illegal Now?).

However, in Goldman the Second Circuit denied interlocutory review and the case settled before any appeal. Hence, the issue didn’t reach the Second Circuit in that case.

The split between the Ninth Circuit and the trial courts in the southern district of New York leaves website owners with a difficult decision – do they assume that Ninth Circuit law is controlling, and therefore continue to embed images? Clearly, for trial judges in SDNY the answer is “no” – these courts, at least, have made clear that they view this practice to be a violation of the right of public display. And, since a copyright plaintiff can often engage in “forum shopping” and file a copyright suit in that district the only safe conclusion is that this practice should be avoided nationwide, at least until one of the southern district cases reaches the Second Circuit on appeal and the split between the SDNY and the Ninth Circuit is resolved. If the Second Circuit creates a circuit split with the Ninth Circuit at the appellate level, the issue would be ripe for Supreme Court review.

There is another dimension to this issue that bears mentioning: the copyright issues are intertwined with complex terms, conditions and technical measures imposed by photo hosting services.

The poster child for this is Instagram. Instagram is the most popular source of images for embedded images, and it facilitates embedding by providing an embedding API. Late last year Instagram introduced a new feature allowing copyright owners to disable the embedding feature for photos they post. Before that, Instagram posters had to elect to use a private account to block unwanted embedding.

Instagram’s change to its embedding policy may reduce the likelihood of future copyright cases on this issue, but not by much. Many Instagram posters are unlikely to become aware of or implement this feature. Other social media and photo hosting sites, such as Twitter, Facebook and Flickr, have not followed Instagram’s policy. And, of course, there are millions of hobbyist and small-business sites that will not bother to block photo embedding, making it likely that this issue will continue to be the subject of litigation.

Stay tuned.

McGucken v. Newsweek LLC (S.D. N.Y. March 21, 2022)

Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, LLC 302 F.Supp.3d 585 (S.D.N.Y 2018)

by Lee Gesmer | Mar 18, 2022 | Copyright

The scope of copyright law is vast – it protects traditional art forms such as books, music, photos and paintings, but also covers more exotic forms of expression, such as computer software, choreography, literary and movie characters (Batman, James Bond) and even useful objects (product and clothing designs).

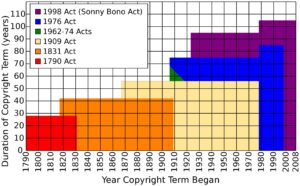

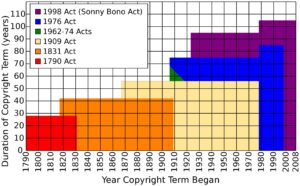

However, it can be difficult to determine whether a particular work is protected by copyright due to the passage of time or failure to comply with once-essential “formalities.” Many people know that under current copyright law a copyright lasts for the “life of the author plus 70 years” or, if the work was created by an employee and is a “work for hire” 95 years from publication. Unfortunately, for older works it’s not that simple – duration is complicated by the fact that as Congress has increased the term of copyright protection for new works it has had to struggle with readjusting the term for older works, leading to a series of arcane retroactive rules that control the copyright status of what have come to be known as “orphan works.”

THE FOUR COPYRIGHT ERAS

There are four major time periods – four “eras” – that need to be considered when determining whether a work is protected by copyright or has entered the public domain.

THE FIRST ERA: Pre-1923

Although all works published before 1923 are in the public domain today, historical context is helpful to understanding copyright duration. To find that we have to look back more than a century, to the Copyright Act of 1909. Relatively speaking, copyright protection was short then. Between 1909 and 1923 works registered with the Copyright Office were protected for 28 years from publication.

At the end of the 28 year term the owner had the option to renew the copyright. If the owner renewed protection was extended for a second consecutive 28 year term, known as the “renewal term”. Thus, with renewal works could be protected for a total of 56 years. Congress has not extended the copyright for pre-1923 works, and therefore they are in the public domain whether their copyright lasted 28 or 56 years.

THE SECOND ERA: 1923 – 1963

In 1996 Congress passed the Copyright Term Extension Act, which became effective in 1998. This law increased the copyright term for works published after that date. At the same time it reset the term for works published between 1923 and 1963. Works whose registration was still in their first term or had been renewed (by then the renewal term had been extended to 47 years, extending the full two terms to 75 years and making it possible for works published in 1923 to remain protected in 1998) were given a new life – 95 years from publication. This created a 20 year “gap” during which works that would have entered the public domain in 1998 were protected for an additional 20 years. However, the 20 year period has lapsed, and these works have been falling into the public domain annually each year since 2019. Works published in 1923 entered the public domain on January 1, 2019, works published in 1924 in 2020, and so on. To date works published in 1923, 1924, 1925 and 1926 have entered the public domain. This process will continue until 2057 when, finally, works published in 1961 will enter the public domain.

THE THIRD ERA: 1964 – 1977

Expansion of U.S. copyright law (assuming authors create their works 35 years before their death)

The third major era covers the years from 1964-1977. Once again, when Congress changed the rules in 1998 it changed the term for these works retroactively. Works published during these years are protected for 95 years, and there is no registration or renewal requirement. Thus, a work published in 1964 will fall out of copyright on January 1, 2059, works published in 1965 in 2060, and continuing until 2072, when the final cohort – 1977 works – will lose protection.

THE FOURTH ERA: 1978 – PRESENT

Works published after January 1, 1978 are protected for the life of the author + 70 years or, in the case of works for hire, 95 years. Works for hire – works created by employees – are a large share of copyright-protected works. For example, all Hollywood movies are works for hire, and therefore a movie released in 2022 will be protected for 95 years, until 2117.

The “life + 70 years” term has the potential for even longer duration for works that are not works for hire – the 30 year old author of a book published today might live another 60 years, to age 90. That 60 years, plus 70 years following the author’s death, could result in the work being protected for 130 years, until 2152. This will be true even if the author sells or assigns the work – the life of the copyright continues to run based on the life of the author, even after the author no longer owns the copyright.

ORPHAN WORKS – DETERMINING WHETHER A WORK IS PROTECTED CAN BE DIFFICULT

As this trip through history shows there has been a slow but continuous expansion of copyright duration from 28 years in 1909 to potentially well over 100 years today.

However, the fact that Congress has enacted rules retroactively can make it difficult to determine whether many older works are still under copyright. Owners can’t be identified or located and registration records are imperfect – it can be difficult to determine whether the author complied with mandatory registration and renewal requirements, or even who owns the copyright today. A copyright may have been lost based on publication without a proper copyright notice (notice was mandatory before 1977). The Duke Law School Center for the Study of the Public Domain reports that most older works are “orphan works,” where the copyright owner cannot be found at all.

Nevertheless, potential users of orphan works cannot blame inefficiencies in the system – the obligation to perform thorough research and “clear” a work rests with those wishing to use these works. Failure to do so could result in an expensive claim of copyright infringement.

Caveat lector: Copyright duration is an exceedingly complex and technical topic. This article should be viewed as a high-level summary of copyright duration for U.S. law. There are legal requirements beyond the rules described here.

District of Massachusetts. ASCAP manages the public performance rights for these songs.

District of Massachusetts. ASCAP manages the public performance rights for these songs. to a publishing company to manage. There are many publishing companies, and the largest own publishing rights to thousands of songs. Two large publishers are the two plaintiffs in this case – Universal Music Publishing and Primary Wave.

to a publishing company to manage. There are many publishing companies, and the largest own publishing rights to thousands of songs. Two large publishers are the two plaintiffs in this case – Universal Music Publishing and Primary Wave.  to bring a copyright infringement lawsuit.

to bring a copyright infringement lawsuit. early/mid-1970s. None of the copyrights have expired. In fact, the composers are still alive, so the copyrights will remain in effect for at least another 70 years. Even though the copyrights have been transferred, their duration continues to follow the lives of the composers.

early/mid-1970s. None of the copyrights have expired. In fact, the composers are still alive, so the copyrights will remain in effect for at least another 70 years. Even though the copyrights have been transferred, their duration continues to follow the lives of the composers.